Working-Class Scholar

Joshua Linkous, PhD Student

Joshua Linkous is a PhD candidate in history who studies peasant societies and industrialization. He talks about his nontraditional path to Harvard Griffin GSAS, upending modern conceptions of the industrialization of Japan through his research, and the camaraderie he’s found among his fellow students.

Nothing Special

I grew up in the Detroit area. My family came from Poland via West Virginia to join the automotive industry, but deindustrialization left the region in a difficult place. On top of chronic job insecurity, my father suffered a disabling head injury while working at a factory when I was a teenager, and my mother got cancer. Like many Americans during that time, we also didn’t have any health coverage, which made staying afloat even more difficult. The burden fell entirely on my eldest sister’s shoulders. I felt horrible about this and also knew she couldn’t earn enough. For these reasons, I decided to leave school at 16 to work and help support my family.

At the time, the decision to quit school didn’t feel like anything special. I’d seen other people do it. I had family and friends who had done it. On top of that, our schools generally ranked among the worst in the country. I had nobody to show me what I had to do to succeed and go to college. I didn’t know what kind of help I could get. Without that support, it was easy to feel that my life had already reached a dead end with nowhere else to go. For that reason, when I left school, I thought I was just speeding up the process of where I would be anyway. I didn’t believe there could be a different future.

Over the next five years, I worked various kinds of jobs. I was often treated as a degenerate. When I interviewed for jobs and people saw that I left school, they would ask me questions like, “How many times have you been in prison?” “How many tattoos do you have?” “How many women have you gotten pregnant?” and so on.

Employers knew that since I was a high school dropout, I was not in a position of power and they could take advantage of me. I left school sometime around the 2007 financial crisis when unemployment in the Detroit area was very high. Like a lot of folks, I turned to “under the table” jobs—work that was on a cash basis and off the books. One time I worked in construction 14 hours a day for a week only to have the boss renege on most of my wages and pay me only $70—a dollar an hour. Experiences like that are in part why I developed a passion for telling untold stories, especially those that too often fall outside the remit of economic history.

You internalize what people say about you, and it’s hard to break out of that mentality. I wanted to get out of that situation, not just for myself, but to show other people in my community that we could do something—show them a new way. So I went to community college. It was the first place where I was treated with respect. Community college changed the way I perceived myself. I saw that I had worth and potential.

I did well and was accepted to the University of Pennsylvania, where I got my bachelor’s degree. All of my professors were role models for me. They inspired in me a passion for research and, especially, for teaching. When I graduated, I got my master’s degree at the University of British Columbia, where I had a lot of leeway to design and lead courses. By then I knew that I wanted to teach, but I wasn’t sure that I wanted to do a PhD. Watching my students get excited in class reminded me of my own academic journey so I decided to continue it and ended up at Harvard Griffin GSAS.

A Rough Transformation

When people talk about Japanese history, they invariably mention that Japan was the first non-Western country to industrialize. That misleads people into thinking that Japan must have looked something like Britain after its industrial revolution—an affluent, urbanized society with a growing mass consumer culture.

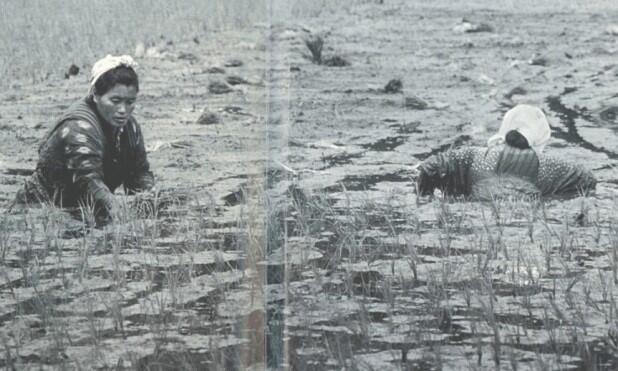

What most people don’t know is that until after World War II, Japan was a mostly rural, agricultural society despite industrialization. Along those lines, my research tracks the attempts of government and local actors to transform agrarian peasants into commercial farmers primarily through the cultivation of rice.

It was a rough transformation. At first, the peasants didn’t want to be commercial farmers and they resisted attempts to dispossess them of their customary rights; for example, the right to have taxes paid in kind or be exempted altogether rather than pay at fixed intervals in money, which provided flexibility to deal with periods of scarcity.

The effect of the resistance was limited because the landlords—who often raised rent and taxes beyond the ability of their tenants to pay—held immense political power. They sought to increase production and profit through the implementation of new technologies that were often incompatible with local climates and agricultural conditions. For instance, the introduction of newly bred rice strains required more intensive inputs and longer growing periods, neither of which the farmers could afford due to the harshly cold climate and the general poverty of the region.

These technologies undermined the stability of agricultural yields and created massive, recurring crop failures. In the literature, these crop failures are portrayed as natural, but the scarcity was actually man-made. Over time, the peasants found themselves required to produce more with less while the landlords pocketed the profits.

Today, a lot of development agencies point to Japan as a model for how nations should industrialize. But development was a huge hardship for the peasant class. There were many pitfalls—not least of all mass starvation—that we don’t want to replicate in the modern world.

Flexibility and Friendship

I talk to a lot of people outside of Harvard, and they are not always able to do a lot of the things that we do. The flexibility students get here is not something you see in other institutions. You can really curate your own educational experience. I was able to take a course on agrarian society and peasants at Yale, and I was able to create my own course on peasant studies with a historian from the University of London. A lot of universities micromanage you through the PhD, but Harvard Griffin GSAS allows you to create a truly unique experience based on how your interests evolve.

Within the graduate community, there is so much camaraderie that goes beyond the eagerness for intellectual exchange. The level of friendship and mutual support is deeper than the cliché of students talking in a stairwell; there is a real willingness to fight for each other that I find very heartening.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast