Weapon of Exclusion, Tool of Liberation

How religion fueled anti-immigration policies—and became a conduit for resistance

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

One of the few things presidential candidates Donald Trump and Kamala Harris have in common is that they are both children of immigrants. Trump’s mother, Mary Anne, was born in Scotland; Harris’s mother in India, and her father in Jamaica. Yet, immigration policy is one of the most divisive issues of the 2024 campaign: Trump promises to target millions of undocumented migrants for the largest mass deportation in US history if elected; Harris advocates for a pathway to citizenship, stronger border security measures, and closing asylum loopholes.

Historian Seokweon Jeon says this type of political and cognitive dissonance on the issue of immigration is actually as American as apple pie. While those in the US like to wax nostalgic about the “huddled masses” passing through New York’s Ellis Island in the late 1800s, Jeon says this “golden age” of immigration was actually a time when the United States developed the most extensive and sophisticated system of control and deportation the world has ever known. “These laws were part of a broader system that differentiated between ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ immigrants, often rooted in racial and religious hierarchies,” he says. “The idealistic story of a welcoming America overlooks the exclusionary policies and the severe barriers to entry and citizenship many groups faced.”

As a PhD student in the study of religion at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Jeon explores how racism and religion interacted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to affect migrants from Asia in particular. His work challenges the romanticized notion of the US as a land of equal opportunity, centering stories of exclusion—often presented as necessary to preserve the country’s moral and social fabric—to reveal how deeply embedded race and religion are in the concept of American citizenship.

Moral Policing

Men and women from China first came to the US in substantial numbers to prospect during the California Gold Rush of 1849 to 1855. Later, many transitioned to the construction of the transcontinental railroad. When they did, they often encountered prejudice from working-class whites—themselves often first- or second-generation European immigrants—who believed their Asian counterparts would be a source of low-wage labor, a fear still exploited today by politicians.

Jeon says that, from the beginning, religious and moral rhetoric was central to crafting exclusionary policies against Asians. “The 1875 Page Act and subsequent anti-Asian bills between the 1880s and 1910s offer key examples of how religious narratives were used to justify exclusion and how this strategy evolved over time,” he says. “Initially, the Page Act targeted Chinese women under the guise of protecting 'public morality,' framing them as potential prostitutes. In effect, it barred nearly all Chinese women from entering the country.”

The 1875 Page Act and subsequent anti-Asian bills between the 1880s and 1910s offer key examples of how religious narratives were used to justify exclusion and how this strategy evolved over time.

—Seokweon Jeon

Jeon says that the Page Act was an example of “moral policing”—where religiously infused narratives about protecting the American family and safeguarding Christian virtue from the perceived “Chinese peril” became powerful tools of exclusion. “As California crafted state-level immigration regulations, it mobilized this story to exclude not just Chinese women but also later “coolie” laborers and other Asian immigrants,” Jeon says. By presenting the exclusions as necessary for maintaining public morality rather than as outright racial discrimination, policymakers were able to sidestep potential diplomatic tensions with countries whose nationals were barred.

Importantly, immigration laws in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were often both restrictive—designed to broadly limit the number of people entering the country—and selective—identifying and determining precisely who was desirable or undesirable based on racial, religious, economic, or geopolitical criteria. “Initially, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was understood as a restrictive measure because it was the first law to prohibit immigration based on ethnicity and national origin, barring Chinese laborers from entering the United States,” Jeon says. “However, it was also highly selective—a tendency that became a general rule applied to Asian immigrants more broadly and persisted well into the mid-twentieth century.”

The 1882 Act and its subsequent renewals allowed entry for certain categories of Chinese immigrants—merchants, diplomats, and students—while barring other “undesirables.” Jeon argues that this selectivity was deeply rooted in a racial and religious hierarchy that portrayed Asians as fundamentally unassimilable to the dominant white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant nation. “Exclusion was not solely driven by economic fears of labor competition but also by cultural and religious stereotypes that portrayed Asians as morally and spiritually incompatible with the fabric of American society,” he says.

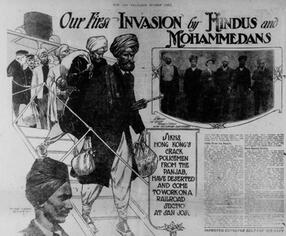

In the early twentieth century, policies like the Immigration Act of 1917 and the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 broadened the scope of exclusion to encompass nearly all Asian immigrants. “Japanese immigrants, often associated with Shinto and Buddhism, and South Asians, labeled the 'Hindoo invasion,' were depicted as religiously and morally incompatible with American Protestant values,” Jeon says. “These narratives did more than reflect economic or racial concerns; they framed Asian immigrants as fundamentally opposed to the Christian ideals seen as central to American national identity. By portraying Asian immigrants as a moral threat, these laws sought to define and defend a racially and religiously homogeneous America.”

White Protestant leaders, including those from more liberal denominations, were key architects of exclusion. Jeon says that, while they often distanced themselves from the overt racism of nativist groups, many liberal Protestant reformers—Methodists, Episcopalians, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians—actively supported exclusionary measures under the banner of preserving America’s “moral” character. “They avoided explicit racial slurs but depicted non-Christian Asians as spiritually dangerous, thus lending a moral legitimacy to laws that targeted Asians based on both race and religion,” he says. “By framing Asian religions as threats to the Christian foundation of the nation, they reinforced exclusionary practices that upheld racial and religious purity.”

This finding that Protestant liberals, not only conservatives, supported exclusionary immigration policies is “groundbreaking,” according to Jeon's faculty advisor, Catherine Brekus, Charles Warren Professor of the History of Religion in America and chair of Harvard’s Committee on the Study of Religion. “We tend to think of anti-immigrant sentiment as reactionary, but in the late 1800s and early 1900s, many white Christians were united by their desire to preserve the white and Protestant identity of the United States,” she explains. “Seokweon’s research asks us to reckon with the long and ugly legacy of religious support for xenophobia—a legacy that continues to shape our nation’s politics today.”

A Faith-Based Movement for Justice and Equality

While rigorously chronicling oppressive laws and practices, Jeon’s research shows that religion was not only a tool of marginalization but also a powerful resource Asian Americans leveraged to resist exclusion and assert their place within American society. “There has never been a single Christianity in the United States,” observes Brekus. “In the late 1800s and early 1900s, one of the fault lines involved the Bible’s teachings on immigration. Seokweon’s work shows how American Christianity, with its contradictory tendencies toward democratic inclusion and authoritarian power, took multiple political forms.”

Jeon says Asian American Christians actively fought against discriminatory laws from the 1870s to the 1920s by drawing on their faith and religious networks, challenging the xenophobic and racist policies of the time. In California, for instance, Asian American faith leaders, such as those from the Japanese Congregational Church in Fresno, California actively opposed white liberal Christians who preached equality but supported exclusionary policies. “These leaders used church platforms and denominational networks to call out the contradictions between Christian teachings on justice and the endorsement of anti-Asian laws,” Jeon says, “highlighting how those stances betrayed the core principles of their faith.”

There has never been a single Christianity in the United States. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, one of the fault lines involved the Bible’s teachings on immigration.

— Professor Catherine Brekus

In the Midwest, Korean Christian college students drew on their religious education and connections with liberal denominations and voluntary organizations like the YMCA and YWCA to critique the anti-Asian sentiment embedded in immigration laws. “Through essays and speeches, these students confronted the dissonance between the professed values of Christian equality and the realities of racist legislation, framing these laws as both un-American and un-Christian,” Jeon explains. Chinese and Filipino Christian students also rose up, using denominational media platforms to speak out against Asian exclusion. “These young Asian American Christians mobilized their communities and potential allies to resist discriminatory policies, fostering a broader, faith-based movement for justice and equity,” Jeon says.

Erez Manela, Harvard’s Francis Lee Higginson Professor of History and another of Jeon’s faculty mentors, says the PhD candidate’s work has important implications for the often divisive conversation about immigration today. “Seokweon’s research shows how Protestant Christianity in the United States was conflated with Anglo-Saxon racial identity, which meant that Asians could not be good Christians and, therefore, good Americans,” he says. “In the present-day context, it calls on us to pay attention to the ways Christian tropes continue to shape American identity, including common notions about who can, and who cannot, become a ‘good American.’”

[Jeon’s research] calls on us to pay attention to the ways Christian tropes continue to shape American identity, including common notions about who can, and who cannot, become a ‘good American.’

— Professor Erez Manela

At a time when questions of immigration, identity, and national belonging are more pressing than ever, Jeon hopes his research reveals the complex role of religion in shaping modern American views on borders, citizenship, and national belonging—as both a weapon of exclusion and a foundation for liberation. His dissertation uncovers the uncomfortable truth that religion was instrumental in constructing the racial and moral hierarchies used to justify exclusionary practices but also reveals how the same religious frameworks were subverted, reclaimed, and reimagined by Asian American communities as tools of resistance against those very hierarchies.

“By delving into the paradox of faith as both a force of marginalization and a means of empowerment, I’m calling for a deeper reckoning with the legacies of religion in American history,” Jeon says. “Because those legacies continue to shape the present and future of immigration policy and the evolving contours of Asian American identity and belonging.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast