Vital Statistics

How immigrant doctors contribute to health care in the United States

As a child, Mitra Akhtari and her family immigrated to the United States. Back in Iran, her mother had practiced medicine, but in the US, she needed to pass three board exams and complete a residency before she could continue her career. Akhtari remembers her mother working hard to relearn in English the principles of biochemistry, a subject she hadn’t studied since medical school, and to save the money necessary to take the tests. “It took her eight years to be matched into a residency,” recalls Akhtari, who graduated in 2017 with a PhD in economics. “Now she’s a practicing child psychiatrist in El Paso, Texas.”

Akhtari’s mother is among the approximately 25 percent of doctors in the United States categorized as international medical graduates (IMGs). IMGs come to the US from all over the world, often on J-1 visas. They are able to remain in the country if they participate in the government’s Conrad 30 program, which waives the return to home country requirement in exchange for a three-year commitment to serve populations in medically underserved areas. El Paso is considered one of these areas.

When newly inaugurated President Donald Trump released an executive order targeting the emigration of individuals from certain countries, including Iran, Akhtari knew from personal experience that the resulting ban could have an unintended consequence—one that would increase barriers to health care access for the country’s most vulnerable populations.

Assembling a Team

A number of graduate students in economics from Harvard and MIT met after the 2016 presidential election to discuss how they could effect change at a national level. In addition to attending local rallies and protests, they began to consider how, as economists, they could add context to the ongoing debate. “We know how to work with data, we know how to look for data sources,” recalls Akhtari. “We should use our skills to make a difference.”

The students knew that they wanted to work on a relevant and important project, one that would be feasible and utilize available data. After the first executive order on immigration was released, they examined how the policy would impact the sectors immigrants worked in. In part because of Akhtari’s experience, they made the decision to focus on immigrant doctors, and the Immigrant Doctors Project was born.

Mapping the Data

After the group decided on a topic, they needed to find the relevant quantitative information. And that’s when team member Jonathan Roth remembered a ready-made data source.

“Jonathan knew I had data from another project I was working on,” says Adrienne Sabety, a health economist studying toward a PhD in health policy. The fact that an existing data set could be used for the project was huge. “Data can often take a long time to acquire, but because I already had it, I obtained permission to use it for a new purpose relatively quickly and started analyzing it.”

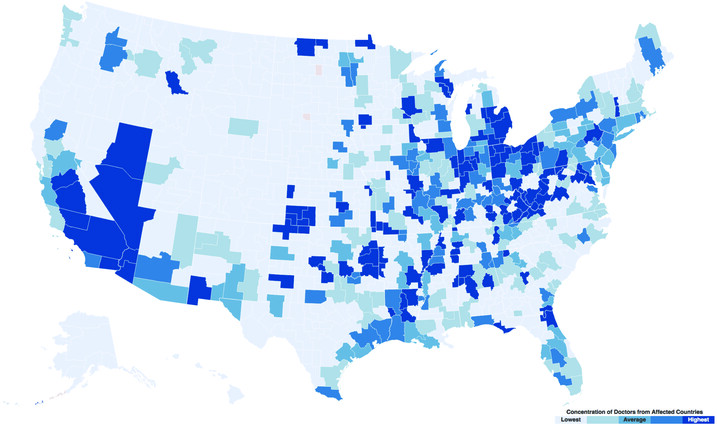

The data came from Doximity, an online networking site for doctors that includes information about where they attended medical school. Focusing on doctors who had received their medical degrees in the countries mentioned in the executive order, they looked at where they worked. The results were astonishing. More than 7,000 doctors from the targeted countries work in the US, and 94 percent of Americans live in a community with at least one of these doctors.

But when a map was created from the data, an even more significant pattern emerged. “We hypothesized that many would be working in rural areas,” says Akhtari. “From personal experience, I knew that people like my mother compete with those trained in the US, who are more likely to get a residency match in more urban cities.” What they didn’t expect, and what the map showed, was that these doctors worked in remote areas and underserved urban areas as well. “We didn’t expect the patterns to be this striking,” she says.

Taking the data a step further, they theorized that a doctor offering 40 appointments a week would offer 2,000 appointments a year and added that information to the map. The highest concentrations, shown in dark blue (see map), are in the Rust Belt and certain urban areas: Los Angeles, Jacksonville, Florida, West Virginia. For example, in Los Angeles, the more than 500 doctors from banned countries provided more than 1,000,000 patient appointments each year. All told, 14 million appointments could be lost if these doctors were not allowed to practice in the US.

Matthew Basilico, an MD/PhD student in economics, brought his knowledge of the medical system and his training in economics to the project. Through work with Jim Kim, PhD ’93, at the World Bank and at other institutions such as Boston Healthcare for the Homeless and Partners in Health, he also was involved in efforts to push health care institutions to be more responsive to the needs of low-income people. He believes that the United States, similarly to poorer regions of the world, suffers from massive health inequalities and injustices.

“Poverty, limited resources, and racial and other forms of discrimination determine unequal access to health care in the United States just as they do globally,” he says. “Even though the belief that health care is a right and that every human should have access to health care is a somewhat universal human aspiration, unfortunately, health care inequities remain stark.”

Challenging Perceptions

To effect the kind of change they hoped for when the project began, they knew they had to add to the conversation about how the policy changes could affect Americans. “What contribution do medical graduates from the affected countries make to the US health care workforce?” asks Basilico. “That is an important question for the public to consider if the country decides to go forward with these policies.” When word came that a second executive order on immigration was imminent, the team worked against the clock to finalize their results. As the second order was announced, ImmigrantDoctors.org and its Twitter account went live.

The team started fielding messages from CNN, The Boston Globe, US News, and Time magazine. While the attention was welcome, the group also wanted coverage in areas most likely to be impacted. “We wanted coverage in areas where immigrants might not be seen as an important part of society,” says Akhtari. “We, of course, welcomed interest by the national press but also wanted our results to appear in local newspapers.” Media from across the country covered the story, from Buffalo, New York, to Los Angeles County, from Utah to North Carolina.

Akhtari was especially pleased by the engagement on social media, which showed that individuals outside of policy circles were connecting with the topic. “People on Twitter commented ‘I had no idea that these doctors were working in underserved areas, thank you for this analysis’;” she says. “The fact that we influenced beliefs about how immigrants contribute to society, that was much more powerful for me.”

The project attracted the attention of the New York Attorney General’s Office, which reached out to ask for assistance in preparing a declaration about the analysis, focusing on the number of doctors in the state, the areas they serve, how many appointments would be lost, and more. After pulling the statistics, Akhtari helped write the brief and the declaration. The group also provided statistics for the amicus briefs filed by the state of Hawaii seeking a temporary restraining order on the executive orders.

While the multiple iterations of the executive orders only seek to restrict immigration from a small number of countries, Basilico has already seen a shift in attitude among the international medical students he works with at Massachusetts General Hospital—many of whom would have moved onto residencies and sometimes careers in the US. “I am concerned that there is already a change in perception about what it is like to train in the United States,” he shares. “I and my colleagues emphasize how welcoming medicine is to individuals who’ve done their initial training in foreign countries; however, I do wonder whether we will see a reduction in interest for training in this country.”

The Big Picture

In 2016, the Association of Medical Colleges reported that the demand for physicians in the United States was growing faster than the supply and projected a shortfall of between 61,700 and 94,700 physicians by 2025. One of the most vulnerable populations affected by this deficit are people in the Rust Belt, those living in rural and remote areas who have limited access to medical services. The data analyzed by the Immigrant Doctors Project demonstrated how those people, and those in underserved urban areas, could lose what care currently exists.

The fact that we influenced beliefs about how immigrants contribute to society, that was much more powerful for me." - Mitra Akhtari, PhD '17

The project also provided an opportunity for a group of students trained in econometrics and in medicine to use their skills to produce a rigorous analysis of a situation with the potential to affect millions of Americans—while contributing to the public conversation about proposed policies. “There’s a reason that we work hard to get the skills we have,” says Basilico. “We believe that one day our efforts can have a positive social impact, and possibly an impact on policy.”

Akhtari agrees. “In graduate school, I tried to work on research that was important and that applied to the real world,” she says. “This project was by far the most impactful and relevant thing that I did in graduate school.” Sabety, too, found the opportunity to use data to effect change inspiring. “Working with disadvantaged populations is really important to me; it’s part of my research agenda,” she shares. “The Immigrant Doctors Project is very powerful. The more we can work on real-world issues, the more change we can effect.”

Illustration by Janice Kun

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast