Tackling TB

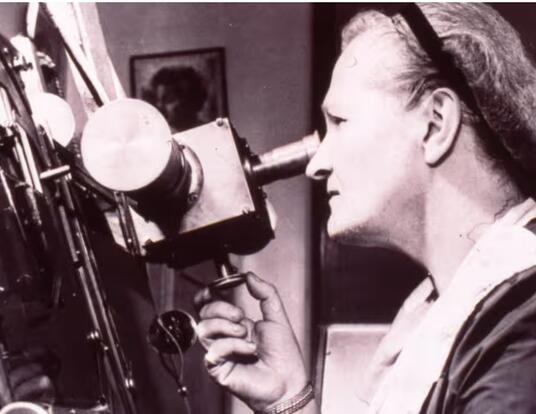

GSAS Voices: Sydney Stanley, PhD '23

Throughout its 150th anniversary year, GSAS is foregrounding the voices of some of its most remarkable alumni and students as they speak about their work, its impact, and their experiences at the School.

Sydney Stanley studies immunology and infectious disease. She discusses her research on the evolutionary genetics of the bacteria that cause tuberculosis, how her findings can improve the tools utilized to fight the disease, and her plans to take on another bacterial pathogen—streptococcus—after she graduates.

Mutations in Microbes

I’m fascinated with understanding how very small organisms can cause infectious diseases that have a big impact on global health. Outbreaks usually follow the fault lines of a society, disproportionately burdening those affected by poverty, malnutrition, comorbid illnesses, or discrimination. So, I’m also motivated to study infectious diseases to contribute to the mitigation of global health disparities.

At Harvard, I study Mycobacterium tuberculosis, or Mtb, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB). We don’t see a lot of TB here in the United States, but it’s the deadliest infectious disease in the rest of the world, only recently challenged by COVID-19. I have studied pathogens’ importance to global health since I was an undergraduate at Duke University, so it’s been rewarding to continue this mission at Harvard, working on Mtb while the world grappled with the COVID-19 pandemic.

TB is a major threat to global health because the vaccine is largely ineffective. Therapy includes multiple antibiotics that have to be taken over a course of several months, and infection is difficult to detect. You can imagine that the shortcomings of the tools currently used to combat the TB pandemic are compounded in resource-limited settings—which contributes to the spread and ultimately the mortality of the disease.

In Professor Sarah Fortune’s lab, I research the evolution of Mtb and demonstrate that genetic changes that occurred hundreds to thousands of years ago are associated with differences in the transmission of TB, antibiotic efficacy, pathogenesis, and disease severity today. Defining the functional effects of these ancient mutations is important because they are typically overlooked in favor of more contemporary mutations when designing new ways to improve TB antibiotics and diagnostics.

Sequencing Strains for Superior Treatment

My biggest accomplishment at GSAS has been the characterization of a family of Mtb strains from Southeast Asia that have mutated to adapt to their biogeographic context, which incidentally rendered them more susceptible to newly developed TB drugs. My colleagues and I in Professor Fortune’s lab collaborated with a research group in Vietnam, which is a country with a high burden of TB. They collected Mtb samples from TB patients in Ho Chi Minh City, and we sequenced the bacterial genomes to analyze their mutations and assess their fitness in the face of different challenges that simulate infection—including antibiotics.

We discovered a subgroup of these strains acquired a set of mutations approximately 100 years ago that is linked to increased susceptibility to TB antibiotics that were developed within the last decade. Patients infected with these strains may benefit more from these newer antibiotics compared to antibiotics that are part of the standard drug regimen. We see that this subgroup of strains is also associated with cavities in the lungs, the treatment failure in response to traditional antibiotics, and potentially even increased transmission in Vietnam.

Studying these mutations can enable the design of better diagnostics and better drug combinations to detect and treat infections based on ancient mutations in Mtb. Currently we employ a one-size-fits-all approach to TB therapy, but Mtb can be genetically distinct in different regions of the world, so we should tailor diagnostics and antibiotics accordingly.

Amazing Scientists, Even Better People

My graduation from GSAS last May wouldn’t have been possible without the support and guidance I received from my mentor and principal investigator, Sarah Fortune. I appreciate how she entrusted me with compelling projects while also encouraging me to explore my personal scientific interests and creativity. The postdoctoral fellows in my lab, Xin Wang and Qingyun Liu, were also instrumental in my training and development. It was a wonderful experience working with such amazing scientists who happen to be even better people.

Now I will embark on a postdoctoral fellowship at Boston Children’s Hospital studying streptococcus bacteria—another important human pathogen. Eventually, I will pursue further training in clinical microbiology and one day a professorship so I can continue studying infectious diseases and creating knowledge that will ultimately help those who need it the most.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast