Secrets of the Dead

A 4,500-year-old cemetery sheds light on the way that ancient Egyptians lived

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

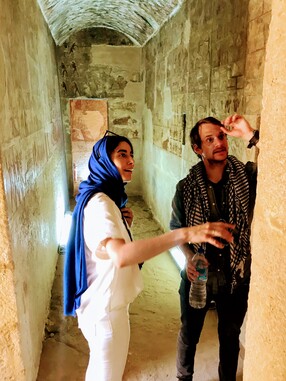

Sixteen-year-old Julia Puglisi was in Egypt’s Western Desert visiting a group of archaeologists working at the site of an ancient frontier town. Suddenly, she came upon an artifact—a wine vessel thousands of years old. She was entranced. Her mind filled with questions.

“It was beautiful,” Puglisi says. “It was built to filter out the bits and pieces of the grapes. I picked it up and thought ‘Who was the last person to hold this? Did they use this to celebrate family ties? To celebrate love with someone? To cope with their problems?’”

The vessel stayed in Egypt, but Julia Puglisi has carried the questions it inspired into her studies at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. As an Egyptology PhD student in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, she uncovers the secrets of one of antiquity's most understudied sites—the quarry turned graveyard known as the Central Field of the Giza Necropolis—for clues about the ways in which art, politics, religion, and culture changed in one of the most influential societies in human history.

A Humbling Experience

Considering Puglisi’s family, it’s a wonder she didn’t end up a scientist. Her parents, both structural biologists, met at MIT and now sit on the faculty of Stanford Medical School. Her mother grew up in Parma, Italy, though, and sent Puglisi every summer to stay at the family home—a 400-year-old tower that had originally been part of a network of beacons. (Think Lord of the Rings or Game of Thrones.) She grew up speaking Italian and harboring a passion for the past. When she turned 14, her father took her to Egypt for the first time. Puglisi was awestruck.

“You have to take a taxi to reach the Giza plateau,” she remembers. “When you get there, the first pyramid that you see is the Great Pyramid of Khufu. No photograph that I've ever seen could do this monument justice. I was deeply humbled. I still am.”

Puglisi knew then that she wanted to study Egypt, but when she got to college at the University of California, Berkeley, she decided to study ancient Greece instead because she “needed perspective.”

“I felt that I needed the background to understand Egypt,” she says. “I needed to understand how the outside world perceived that society. I wanted to get as close to Egypt as I could without actually touching it.”

The downside of Puglisi’s interdisciplinary approach was that it made it challenging for her to gain acceptance into PhD programs in Egyptology. To bolster her credentials, she enrolled for a master’s degree at Indiana University, Bloomington, where she learned to incorporate the digital humanities in the study of ancient Egypt. At GSAS, she continues to apply digital methodologies in her research through the Harvard Giza Project, but completed her last year of coursework at the American University in Cairo. It was there that she discovered how deeply the ancient past can be embedded in a contemporary culture.

“Ancient Egypt is still very much alive,” she says. “Ancient Egyptian language has survived in modern Egyptian Arabic. Some local medical practices are inspired and derived from ancient Egyptian medicine. And there are still some places in upper Egypt where agriculture is almost the same as it was thousands of years ago.”

In Cairo, Puglisi experienced antiquity infused into a living present and, retaining her awe for the great monuments in Giza, honed the questions that inspire her research at GSAS.

“The pyramids are secrets hidden in plain sight,” she says. “We have an idea of what they are, but what did they mean for the common ancient Egyptian? What did they symbolize? Why spend all this time and labor building these monuments? What does that mean for us as humans?”

Searching in the Central Field

To address these questions, Puglisi travels frequently to Egypt—although not since the University curtailed research-related travel in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. There, her work is centered in the Giza Necropolis, the site of the pyramids of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, who ruled during Egypt’s Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE). But the primary object of Puglisi’s study is not these massive monuments, nor the nearby Sphinx, but the adjacent area where the stone for the pyramids was quarried—itself the subject of much misunderstanding.

“There’s a misconception that these massive stones for the pyramids were extracted far away from the site and then hauled over through some superhuman effort,” she says. “In fact, it was quarried only 500 meters away. They had the stone right there.”

When Khufu died, his rule passed to his son Djedefre, who constructed his pyramid in Abu Rawash in northern Egypt. Later, Djedefre’s brother Khafre assumed the throne. He followed his father’s example and decided to be buried in Giza. But instead of burying his queens in smaller neighboring pyramids as Khufu had done, Khafre had their tombs carved out of the quarry where the stone for his monument was extracted. The site, which Egyptologists call the Central Field, became popular with other members of the royal family and the king’s entourage who wanted to be buried close to Khafre and Khufu who were, after all, considered gods.

“This is how the Central Field transformed from a quarry into a cemetery,” Puglisi explains. “Private individuals who didn’t build pyramids, took advantage of the fact that you have all these exposed blocks of stone, so why not just carve into these blocks and make rock-cut tombs? Most of the necropolis is actually used up by these private or royal individuals who are not buried in pyramids. The most interesting stuff is not within the pyramids themselves but encircling them!”

Among the “interesting stuff” that Puglisi studies in her research are the architectural innovations represented by the tombs. As the site of the first rock-cut resting places in Egypt, for instance, the Central Field illustrates the ways in which Egyptians both reacted to their environment and tried to mold it to their own needs. Equally important are the political, social, religious, and cultural changes represented by the ebbs and flows of interest in the burial site over a thousand years. The Central Field starts as a royal cemetery but soon becomes populated by private individuals, signaling a shift in power at the top of Egyptian society in the fourth dynasty.

The pyramids are secrets hidden in plain sight. We have an idea of what they are, but what did they mean for the common ancient Egyptian?

“The viziers—sort of the vice presidents in the dynasty—buried in the Central Field are the last royal viziers of the Old Kingdom,” Puglisi explains. “This is a time when there’s a lot of infighting and jockeying for position in the royal family, which is quite large. The king starts moving administrative responsibilities outside the core of the family. Non-royal individuals start to accumulate a lot of power. It’s the beginning of the end of the Fourth Dynasty, but it also contributes to one of the most colorful periods of the Old Kingdom in the Fifth Dynasty.”

Puglisi’s research also explores the religious changes and tensions at play in the cemetery. The Central Field in some ways became a field of battle between the different gods worshipped by Egyptians. It was also the place that chronicled the rise of new sects.

“There's always been tension between the god of the sun, Ra, and the god Horus, who is this falcon-headed god that represents kingship,” she says. “There is something new that appears in the cemetery during the Old Kingdom: the rise of the cult of Osiris, the god of the dead, which continues well into the Ptolemaic and Christian eras.”

Barbara Bell Professor of Egyptology Peter Der Manuelian, Puglisi’s advisor, says that although the Central Field was excavated in the 20th century, no systematic or holistic approach to understanding the area and its development has ever been attempted. Puglisi’s research can help fill that gap.

“There are unique examples of mortuary architecture, important historical inscriptions, and wonderful three-dimensional sculptures at the Central Field,” Der Manuelian says. “Julia’s combination of Egyptological and digital humanities skills make her an ideal candidate to tackle the job.”

Puglisi says that she hopes she can convey through her work the feeling she had when she held that wine vessel in her hands at 16—the connection with those who lived thousands of years before, the curiosity about who they were and how they lived, and the realization that they are still with us, shaping each moment of our present in ways that often go unrecognized.

“A lot has changed in four thousand years,” she acknowledges. “We don't worship the gods as the ancient Egyptians did. Our worldview has changed too. We're more globalized, less individualistic, perhaps more homogenous as a culture. But there's still something that ties us to ancient Egypt and to an ancient person. It’s the joy of living, the joy of being part of a society, of having great pride in your culture and in your family. It’s reacting to social, cultural, political, and environmental change and making something out of it, persevering. These are the special elements that you find in in the Central Field.”

Photos by Tony Rinaldo and Courtesy of Julia Puglisi and The Giza Project

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast