Re-Shaping American Identity

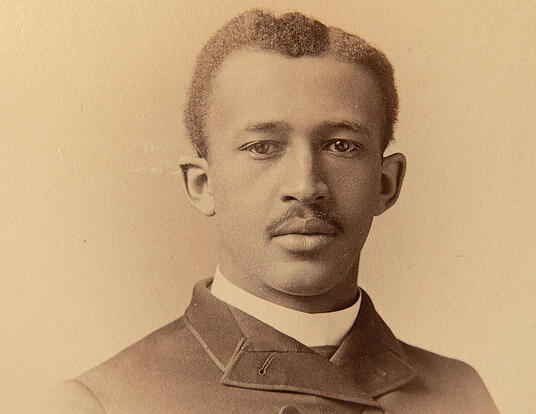

Sociologist Tomás Jiménez, PhD ’05, doesn’t think Americans are rolling up the welcome mat for new immigrants.

In East Palo Alto, California, teens eagerly anticipate going to their friends’ quinceañera parties—even if they’re not Latinx themselves. In Cupertino, every kid can tell you when Diwali is this year—not just the children from Hindu families. To Tomás Jiménez, an associate professor of sociology at Stanford University, these small-scale cultural exchanges are signs of hope. In his new book, The Other Side of Assimilation, Jiménez posits that it’s not just immigrants who are changed by their assimilation into American life, but also the established communities who are changed by the immigrants in their midst.

As a PhD student, Jiménez was part of the second cohort of students affiliated with the Multidisciplinary Program in Inequality and Social Policy based at Harvard Kennedy School. He says that this program, and his mentor Mary Waters, the John L. Loeb Professor of Sociology at Harvard University, had a profound impact on his approach to research.

“I was encouraged to do solid research, and to make it relevant to both an academic and a policy audience,” says Jiménez.

This approach led Jiménez to explore what he feels is an underreported story about immigration in America.

“There is a common observation that immigration is changing everything, but I wanted to dive deeper than just asking whether established communities see immigrants as an economic or cultural threat,” says Jiménez.

In Jiménez’s research, nothing illuminated the push and pull of immigrant-establishment relations quite as well as intermarriage. When a young person from an established family marries someone from an immigrant family, both families have to make adjustments.

“Intermarriage changes the outlook of the older generation, the parents whose children have married newcomers. It changes what they do during holidays. It changes what they believe to be the ethnic and racial mainstream,” he says.

Jiménez looked at a variety of communities in northern California for his book, trying to understand the impact that immigrants have had on their established neighbors, including white people. In Cupertino, where many highly-skilled South and East Asian immigrants have settled to work in the tech industry, Asian students were stereotyped as “smart kids,” while whiteness was associated with taking a lackadaisical approach to school. In other communities with high numbers of immigrants, white kids reported feeling like they were missing out on having a strong connection to an ethnic identity, like the one their newcomer peers have.

“Whiteness—its meaning and status—has been upended in some realms of life,” says Jiménez. He also acknowledges that this shakeup of identity and race in America has also led to a disturbing backlash from what Jiménez calls a “very vocal minority” of Americans who have taken to the streets in places like Charlottesville, Virginia, with a violently anti-immigrant message. “Part of what’s precipitating the backlash nationally against immigrants is a perceived threat to whiteness.”

But Jiménez doesn’t want to focus exclusively on that backlash. He looks back on US immigration history and sees a pattern of Americans ultimately embracing the outsiders who were once seen as a threat. As many politicians, including President Trump, call for increased restrictions on immigration, Jiménez believes that it’s important for sociologists to study the lived experience people have with immigrants in their communities.

“If you only pay attention to the loudest people in the room, you miss a lot of the ways that people are working out what it means to belong in American society,” says Jiménez. “It’s important to know who we are when we’re having a national identity crisis. On the whole, we’re a society that’s figuring out how to get along and adjust, even if the process is bumpy.”

Jiménez hopes that more sociologists examine this “other side” of the immigrant assimilation story with as much rigor as they have pursued stories about the backlash to immigration.

“If you look at recent national polling data, a majority of Americans think that immigrants are good for society,” says Jiménez, citing 2017 data from Gallup and NBC News/The Wall Street Journal. “We need to hold that mirror up to a larger audience. We need to reflect back who we really are.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast