The Great Frustration

Cities that were once beacons of opportunity for Black Americans are now places of poverty and despair. How did it happen?

Two children, both Black. Both come from families with decent income—say $100,000 a year. Both grow up in similar circumstances—urban environments that experienced significant deindustrialization. One lives in Detroit. One lives in Pittsburgh. They should both have roughly the same economic prospects, right?

Wrong.

“All else equal, a Black child growing up in Detroit and a Black child growing up in Pittsburgh will have divergent outcomes as adults,” says the Princeton University economist Ellora Derenoncourt, PhD ’19. “The child who grows up in Detroit will have a lower adult income on average than the child in Pittsburgh. That's because of the backlash that resulted from the Great Migration.”

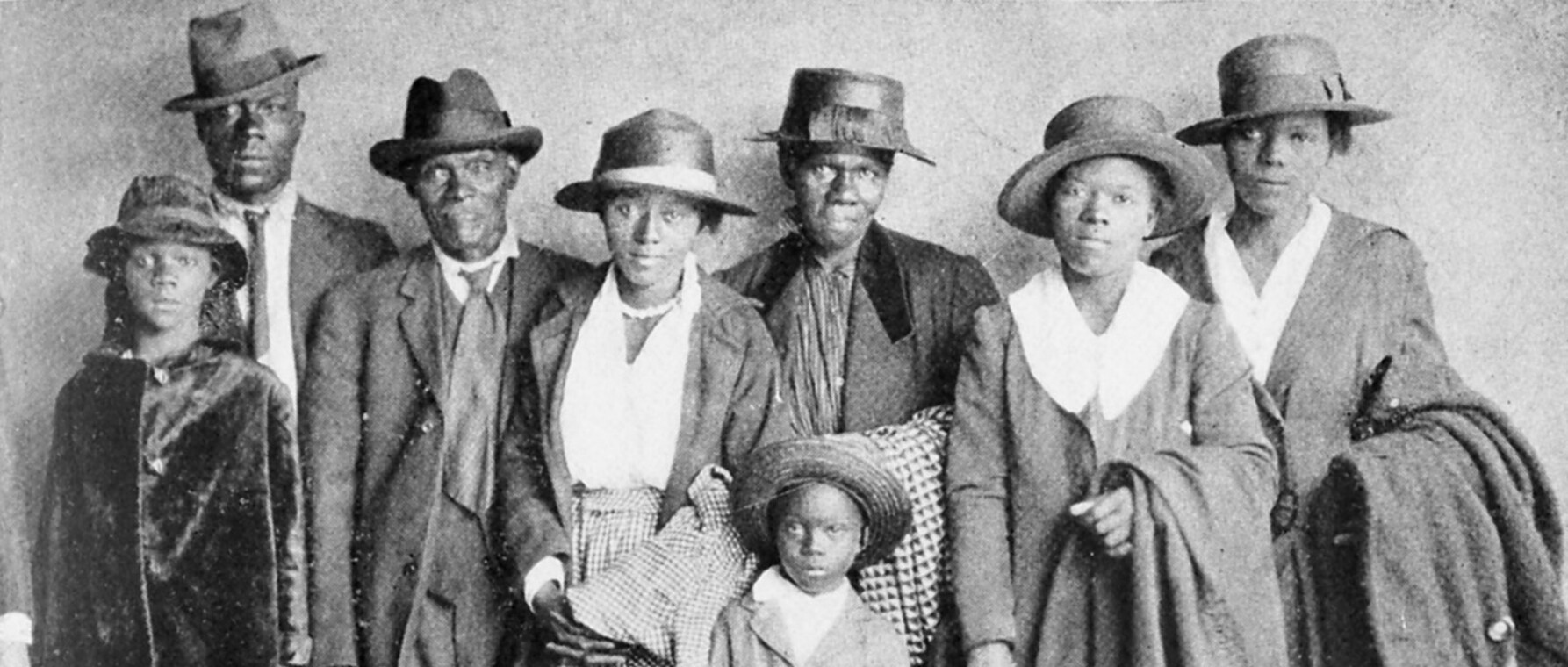

From 1915 to 1970, roughly six million Black Americans moved from the southern United States to the North, Midwest, and West during the Great Migration. They were looking for economic opportunity, social mobility, and a less rigid racial hierarchy. At first, they found it in the country’s great urban and industrial centers. But as Derenoncourt shows in “Can You Move to Opportunity? Evidence from the Great Migration,” the cities where Black Americans most frequently landed over time became traps of social immobility—and remain so to this day. The reasons, she says, have to do with how these communities—particularly white residents and the local governments that represented them—reacted to their changing racial identity.

Moving to Opportunity?

At the center of the American mythos sits a narrative of mobility and opportunity that has driven economic policy throughout the country’s history. The Homestead Act of 1862, for instance, distributed about 270 million acres overwhelmingly to white farmers willing to move, stay, and “improve” previously public land. Slavery and, later, Jim Crow laws in the South restricted most Black Americans’ freedom of movement, however, until the Great Migration. Beginning around the time of the First World War and accelerating during World War II, Black Americans moved by the millions to cities in the North and West.

“Between 1940 and 1970—the years during which most of the migration occurred—the percentage of Black Americans living in the South dropped from 75 percent to around 50 percent,” says Derenoncourt. "It was one of the most significant internal migration episodes in US history."

At first, the gamble seemed to work. Many who moved found a “promised land” of economic opportunity. “Estimates from previous research suggest that migrants could double their earnings by moving North,” Derenoncourt notes. The children of migrants looked poised to benefit as well. Comparing locations around the country in 1940, Derenoncourt says that the cities to which migrants flocked ranked highest in terms of Black children’s educational attainment, even after accounting for parents' education levels.

Cities like Detroit ceased to be beacons of opportunity just as conditions in the South improved economically and socially.

-Ellora Derenoncourt, PhD ’19

“High school attendance among Black teenagers is a pretty meaningful indicator for this period," she says. "There were virtually no public high schools in the South that Black children could attend. Instead, schools were multi-grade, and often low quality. In contrast, 45 percent of low-income Black children went to high school in Detroit. That put the city in the top 20 percent of places in the country for high school attendance rates among low-income Black kids.”

By the 1970s, however, those opportunities had dried up. Today, Derenoncourt’s research shows, economic and educational prospects for Black families living in the former Great Migration destination cities have deteriorated to the point that little difference exists between the North and the South. In recent decades, in fact, a sort of “reverse migration” has begun as Black families move in large numbers to cities like Atlanta and Houston in search of better jobs and housing.

“Cities like Detroit ceased to be beacons of opportunity just as conditions in the South improved economically and socially,” Derenoncourt says. “Black parents living in former Great Migration cities face a choice between raising their children where they'll likely be exposed to violence and the criminal justice system or moving to suburban Atlanta where jobs are better and housing is cheaper.”

The difference in prospects for Black children who grow up in cities that were more affected by the Great Migration versus those that were less affected is stark. “If you grew up in the 1980s and 1990s in a city that was a major destination during the Great Migration,” Derenoncourt says, “you have lower income as an adult on average than kids who grew up in less affected destinations, even holding constant for family income. You may start with the same resources, but you end up in different places.”

But how specifically did these locations change? To understand what these locations were like before, during, and after the Great Migration, Derenoncourt collected data on residential patterns, schools, crime and incarceration, and local government expenditures for former Great Migration locations covering nearly 100 years.

“The Great Migration was a shock to the racial identity of northern cities that produced a multitude of changes,” Derenoncourt says. “One was an increase in the share of the budget dedicated to policing. By contrast, on net, these metropolitan areas did not increase spending on health or education.”

The response by local governments [to the Great Migration] was to invest in punishment and incarceration, a choice that characterized city budgets for decades.

-Ellora Derenoncourt, PhD ’19

Even so, Derenoncourt notes that crime rates rose in Great Migration hubs. The violence and destruction of the urban race riots of the 1960s were also more pronounced there. White flight and racial animus intensified, and economic opportunities became more segregated.

“Jobs moved to the suburbs, as [Harvard Professor] William Julius Wilson describes in his book, When Work Disappears,” she says. “These central city neighborhoods were left without economic opportunity. Under those conditions, we know that crime rates often rise. The critical question is how local governments reacted to this social unrest and urban decline. The response by local governments was to invest in punishment and incarceration, a choice that characterized city budgets for decades.”

Addressing a Legacy of Inequality

The legacy of this response is still with us today, Derenoncourt points out. Black children who grow up in cities most affected by the Great Migration wind up poorer than their cohorts in cities that were less affected, even controlling for family resources.

“What I find specifically is that income gets worse as we move up the ranking of cities affected by the Great Migration,” she says. “Moving one standard deviation up in the ranking [equivalent to going from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Lorain, Ohio, for example] is associated with about an 11 or 12 percent reduction in the adult income of the kids growing up in that location. And it’s about how locations foster good outcomes for children, not about the kind of family that you grow up in.”

Elisabeth Allison Professor of Economics Lawrence Katz, who was one of Derenoncourt's PhD advisors at GSAS, says that her work provides new insight into the historical roots of US racial inequality in wealth, income, wages, and labor market opportunities.

“Ellora’s latest work on the Great Migration brings better sources and top-notch economic modeling to illuminate the long-run evolution of US racial inequality,” he says. “She shows how the promise of increased intergenerational upward economic mobility for Black Americans from the mid-20th century has been thwarted, with punitive criminal justice policies in geographic areas of the North that received substantial inflows of Blacks from the South being a likely contributor.” (Derenoncourt says she is now actively working with a team of researchers on a Russell Sage Foundation-funded project that looks at the direct link between the Great Migration and punitiveness in local jurisdictions.)

Derenoncourt's work also highlights times when policy has acted to help close racial disparities rather than exacerbate them. Katz points to her research on the expansion of the federal minimum wage in the late 1960s and early 1970s to sectors disproportionately employing Black workers, which demonstrated that the policy played a key role in reducing racial economic disparities.

“It was the highest minimum wage we've had in the history of the United States,” Derenoncourt says. “In the late 1960s, the federal minimum wage in today's dollars was over $10 an hour. Today's minimum wage is $7.25. At that time as well, the law was extended to include those we now consider canonical minimum wage workers: restaurant workers, service workers, agricultural workers. Black workers were overrepresented in those sectors, so it was a huge boon to them to have their wage levels lifted. Our estimates suggest the extension of minimum wage coverage reduced the racial earnings gap by as much as civil rights anti-discrimination legislation. Indeed, we help explain a key puzzle around why the improvement in relative Black earnings was so rapid and so large during these years.”

Neighborhoods aren't good because there’s something in the water. They’re good because of the decisions that people make about where to live and where to send their kids to school and decisions that local governments make in response to social conditions.

-Ellora Derenoncourt, PhD ’19

Derenoncourt’s hope for her research is that it will draw attention to the dire circumstances of those who live in communities that once were bastions of opportunity and also inspire simple changes that can have a big impact. Rather than focus exclusively on encouraging families to move from “bad” communities to “good” ones, policymakers can learn what fosters opportunity, equity, and positive outcomes and apply those lessons in the places where people already live.

“Neighborhoods aren't good because there’s something in the water,” she says. “They’re good because of the decisions that people make about where to live and where to send their kids to school and decisions that local governments make in response to social conditions. Research should try to unpack what those things are. I hope my paper is a start to that."

While Derenoncourt is conscious of gridlock in the federal government, she is optimistic about the opportunities for change at the local level. If people come together and organize, they can still affect big change. As evidence, she points to the recent renaissance in the labor movement in traditionally hard to organize sectors like food services. Moreover, cities and states are increasingly willing to enact higher minimum wages even if the federal government will not.

“As localities experiment with alternative approaches, then other places can adopt that blueprint,” she says. “Some policies can start to trickle up to the state level, or labor advocates can put pressure on other large actors as with Amazon and Walmart, who have implemented company-wide minimums that exceed the federal minimum wage. It’s not the same as federal legislation, which has more universal coverage, but you do what you can within the constraints that you have."

Photos Courtesy of Ellora Derenoncourt; Banner Courtesy of Wiki Commons

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast