A Cabinet of Wonders

As Houghton Library turns 75, former and current GSAS students look back at the objects that inspired their research

For some researchers, a library is just a library. It’s a utility, a convenience (or inconvenience) to getting their work done. For others, a library is a treasure map, a time machine, and a cabinet of wonders. It’s hard to imagine even the most jaded student entering the Houghton Library without a sense of awe. Within the walls of Houghton, a scholar can turn the pages of a 16th century German manuscript, read a letter signed personally by Vladimir Lenin, unfold a book of spells from Indonesia, and marvel at Emily Dickinson’s writing desk and chair.

Emilie Hardman, research, instruction, and digital initiatives librarian at Houghton Library begins her tour of the collections with some very groovy artifacts from the 1960s, now on display as a part of the exhibition “Altered States: Sex, Drugs, and Transcendence in the Ludlow-Santo Domingo Library.” This exhibition, which is open through December 16th, features the first X-rated comic book, Barbarella (which became a cult classic film), and former Harvard lecturer Timothy Leary’s notes on his LSD experiments. These modern materials sit in a building that was originally designed for the more staid works of European poets and scholars. Over the years, Houghton Library’s mission, and therefore its collection, has expanded to meet the needs of more contemporary scholarship.

Hardman notes that the Ludlow-Santo Domingo collection is just one of many unusual collections held in the library. “A chemist could come here and study the properties of the rolling papers in the exhibition,” she says. “A biologist could look at historic accounts of disease in our manuscripts from the 17th century. There’s no limit to what a scholar can do with the collection.”

When it was built in 1942, Houghton was the first of its kind: A purpose-built structure for a university’s rare book and manuscript collections. This year, as Houghton celebrates its 75th anniversary, scholars from Houghton’s past and present are taking a look back on the objects that inspired them.

Under Houghton’s Spell

Many students’ first encounter with Houghton happens through a classroom field trip. Katherine Leach, a PhD student in Celtic languages and literatures, has been bringing her students to Houghton for three years.

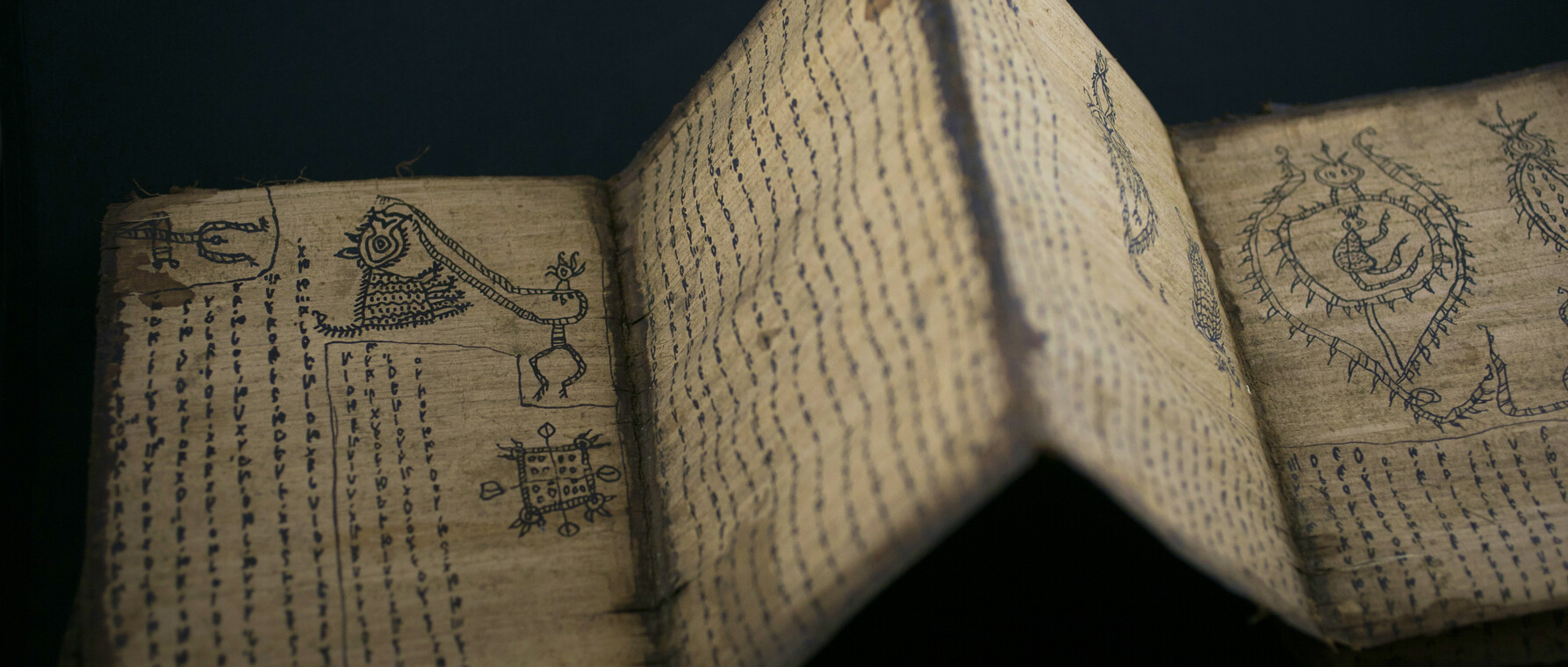

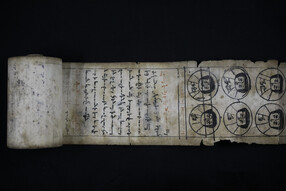

Leach came to Houghton to explore medieval and early modern tracts against witchcraft with her students. Emilie Hardman showed them a variety of original sources from that period, like the Malleus Maleficarum, but also brought in an Indonesian spell book and incised bamboo sticks engraved with spells, as well as an Armenian charm scroll.

“I started out just wanting to get students into Houghton, but it ended up being more than that. The class changed because of what Emilie brought in to show my students,” Leach says. “There were two Armenian students in the class. Seeing that scroll blew their minds. They were posting on Instagram and texting other Armenian students.”

Leach says that as a medievalist, she’s often focused exclusively on texts and manuscripts. These later, non-Western artifacts helped her students connect those texts to the present day, and to expand their thinking about the role of magic and witchcraft in human history.

“I was so impressed with the collection and with Emilie,” Leach says. “Seeing these artifacts made the topic more relatable, more real.”

The Sound of Resistance

Andrea Bohlman, PhD ’12 in music, made her Houghton discovery while doing some last minute internet searches to prepare for a research trip to Poland.

“I was probably on page 57 of search results in the HOLLIS catalog when I stumbled upon the finding aid for the Solidarity Collection,” recalls Bohlman. The Solidarity Collection is comprised of dozens of cassette tapes belonging to Poles who resisted or subverted the Communist government as a part of the Solidarity movement of the 1980s. Bohlman didn’t know quite what the tapes were, but she decided to find out.

After librarians worked with the Harvard Music Library to digitize the tapes, Bohlman visited Houghton, where she was handed a CD player and headphones. The sounds she heard opened up a whole new world of research for her.

Listening to the digitized tapes, Bohlman heard everything from politically-conscious Polish rock music to bootlegged news reports from broadcasters sympathetic to the Solidarity movement. While copies of these tapes still exist in Poland, Polish emigres brought them to places like Paris, Chicago, and Boston. The tapes tell a story of political activism in the 1980s.

“Cassette tapes are convenient materials for politically subversive communication—you can wipe them with a magnet, you can record over them, but you can also copy them infinitely,” says Bohlman.

Solidarity-related cassette tapes became the cornerstone of Bohlman’s dissertation, now a forthcoming book, Musical Solidarities: Political Action and Music in Late Twentieth-Century Poland. Her unexpected encounter with these underground recordings has had a major impact on Bohlman’s approach to scholarship.

“It’s changed my research methodology forever. Now everywhere I go to conduct research, I look for weird sound recordings,” Bohlman says. “They’re an untapped resource.”

A View from on High

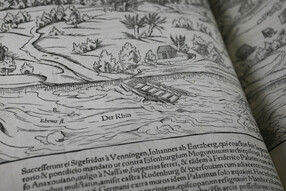

Today, we can zoom in on any part of the world through Google Maps and Google Street View. But for 16th century people, being able to see a view of their own city, or a city they had never visited, was pretty novel. German cosmographer Sebastian Münster had to go about making his Cosmographia, a book intended to describe the entire world, without the benefit of Google maps.

“The innovation Münster had was to put city views in his book,” says Jasper van Putten, PhD ’15 in the history of art and architecture. Van Putten was intrigued by these city views, which he was able to study at length in the Houghton Library. “Münster managed to get local patrons from each German city, and the patrons provided a view of their city and sent that to Münster."

The next step in van Putten’s research would have astonished Münster and his 16th century patrons. He used GIS mapping tools to overlay the city views onto modern day satellite maps of German cities. Using landmarks like church spires or old city walls, van Putten was able to warp the hand-drawn city views over the modern-day cities they represent.

Surprisingly, the city views were fairly accurate to the geography of German cities. However, in some illustrations, patrons nudged important landmarks into positions that made their cities look more important.

“One city moved a castle about 300 meters to put it in the center of the view!” says van Putten.

Not only does Houghton Library hold an original copy of the Cosmographia, it has some original prints that Münster copied, and later French knock-offs that borrowed from Münster’s original images and techniques.

“Researching at Houghton was wonderful because I could compare all of these images at the same time,” van Putten says. “By studying the Houghton holdings, I may have even discovered that some of the city views in these derivative French editions made it back into the Cosmographia’s later editions.”

The Cosmographia stayed in print for about 90 years, and city views were added or redesigned in later editions. When van Putten stacked up the city views in GIS, he could flip backward and forward in time, seeing how views of the city changed. He has put his work online, giving researchers and history buffs anywhere the chance to discover the way that 16th century Germans saw their world.

The Shape of Light

Jeremy Zallen, PhD ’14 in history, wanted to write about the history of illumination for his PhD dissertation. He started looking into the earliest forms of electric light in the United States and came across the records of the Bijou Theatre, held in Houghton Library. In the 1880s, the Bijou, which sat right in downtown Boston, became the first fully-electrified theater in the country. Even more surprising, a single, fragile light bulb survived from that era and sits in Houghton alongside the Theatre’s more mundane financial records.

“I thought it would look very different, but it looks more like light bulbs today,” Zallen says. In fact, if you put this tiny bulb on a shelf in Home Depot, you might not notice that it is a relic from the 1880s, with a bamboo, rather than tungsten, filament.

“The bulb would have been made in Menlo Park, under the direction of Thomas Edison. In those days, they were experimenting with a number of filament types,” says Zallen. “The bamboo filament would have been less bright than previous electric light bulbs, but it would have lasted at least a few days—which was a big improvement.”

Edison himself attended the first few performances at the Bijou, tending the electrical generators backstage.

Zallen says that the bulb brought up more questions than answers: Why did someone save this solitary light bulb? Were the electric lights primary purpose functional, or were they really just props to publicize Edison’s invention?

“Houghton is unusual in that it has early, medieval, and modern 20th century collections,” he says. “Houghton’s the kind of place where you can sit for a while and ask questions—even if you don’t know what the answers are.”

More to Come

Houghton is a place where researchers poring over centuries-old prints can sit side-by-side with researchers digging through rock posters or piles of cassette tapes. It’s a place where a scholar can come in with one question, and come out with 20 more. Emilie Hardman hopes that it will remain a vibrant, ever-evolving place.

“Being able to expand who this library can be useful to is why I come to work every day at Houghton,” says Hardman. “The creative spark that so many people at Harvard can bring to this space is really remarkable. We want this collection to be open and useful to everyone.”

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast