The Bridge

How art connects disciplines and people at Harvard

Near the Harvard Faculty Club at the top of Quincy Street, a concrete ramp rises to bisect the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Standing at its apex, sheltered by a roof that caps the building, you can peer through floor to ceiling windows and watch students hang their paintings to dry or move about in the woodworking shop. From there the ramp descends, taking you at last to the Prescott Street entrance of the new Harvard Art Museums.

This is The Bridge, a physical connection between the Carpenter Center and the Harvard Art Museums that also serves as a metaphoric span demonstrating the important link between the practice of art and the study of art at one of the world’s great research universities.

Forging Relationships

The reopening of the Harvard Art Museums in November 2014 has shined a light on where the arts fit into the University. Thanks to a complete rethinking, the Fogg Museum, the Busch-Reisinger Museum, and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum have been united at the Quincy Street location and brought renewed focus to how Harvard’s art collections can be used as teaching tools. “We want the Harvard Art Museums to be a meeting place for all disciplines,” says Thomas W. Lentz, Elizabeth and John Moors Cabot Director of the Harvard Art Museums.

The programs we are planning won't work without GSAS students. The building isn't going to work without the energy, enthusiasm, and critical questions that these advanced students are raising. —Jessica Martinez

In a way, the Harvard Art Museums’ desire to forge relationships with all disciplines, including engineering and applied sciences, brings art at the University full circle: The first classes in freehand drawing and watercolor painting were offered in the 1870s at the Lawrence Scientific School, the precursor of the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, instruction that was soon expanded to Harvard College students. But it wasn’t until the 1950s when President Nathan Marsh Pusey charged a Committee on the Visual Arts—chaired by one of the Monuments Men, John Nicholas Brown, AB ’22—that a comprehensive evaluation of the arts at Harvard was undertaken. The Committee’s findings, known as the Brown Report, recommended the establishment of a Division of the Visual Arts that would bring together the history of art with an expanded department of design (to include painting, sculpture, graphic arts, and other visual media) and the University’s teaching collections housed at the Fogg and the Busch-Reisinger.

The Brown Report also endorsed the construction of a design center to provide workshop space for student artists, noting that areas for the display of art could be located in a part of the building that overlooked the Fogg as a visible reminder of the connection between art practice and study. The Brown Report led to the development of the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, the Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier’s only US designed building, which now houses the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies, exhibition spaces, studios, classrooms, and the Harvard Film Archive.

An Intellectual Exercise

Sixty years later, the results of the Brown Report still resonate with Jim Voorhies, the first John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Director of the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. “I appreciated the way in which the Brown Report discussed how art making can be an intellectual exercise and equated the knowledge gained through discussion about color and by working and experimenting with materials to the knowledge gained from literature and writing and other humanities,” he says. “It’s really quite beautiful, this intersection of the visual arts and other disciplines.”

For Voorhies, the Carpenter Center is a place where works of art are made, displayed, and discussed, all within a work of art, Le Corbusier’s design. “I like that the Carpenter Center is simultaneously an academic space as well as an exhibition space with its own challenges,” he says. Because of the openness of the architecture, there are few walls for works to hang on; that limitation is a spur to innovation for visiting artists, who must be more inventive when considering how to show their work. “Over the course of a term, we work with artists to see how they respond to the building and to the social and political space of Harvard and Cambridge,” Voorhies says. “Based on their engagement with the building, they create art that can be shown only in this space.” While in residence, artists meet with students and participate in Harvard’s teaching mission. “We essentially stitch the artist into academic life,” he says.

Daring Thinking

Following the ramp down to the new Harvard Art Museums, a visitor moves from the thriving practice of art to a new way of engaging with it. “We preserved the intimate scale of the original facility,” says Lentz. “But we also want to slow people down, to encourage them to look and think more deeply.” This intention to educate is deliberate and allows the museums to firmly embrace their role in Harvard’s teaching mission.

“In recasting the Harvard Art Museums, we brought educators to the table,” says Jessica Martinez, AB ’95, PhD ’04, director of academic and public programs. “We wanted to know what happens when the galleries are installed or the special exhibitions are conceived with teaching in mind, and teaching at the Harvard level.” The result is a museum that serves all its constituents—faculty, graduate students, undergraduates, visitors, and the high school pupils steps away at Cambridge Rindge and Latin—and encourages critical thinking.

“We want to ask viewers, what do you see? Spend some time with the art, now what do you see?” Martinez says. “If you consider the other historical, economic, social, and cultural forces at play, now what do you see? What remains invisible? What requires the kind of academic conversation happening at a great university to fully understand?”

For Martinez, graduate students play a pivotal role in this learning mission. “The programs we are planning won’t work without GSAS students,” she says. “This building isn’t going to work without the energy, enthusiasm, and critical questions that these advanced students are raising. We want to open up the possibilities for their own research and advance the deep thinking that we’re already doing.”

Though just reopened, the Harvard Art Museums’ desire to reach across disciplines is already paying dividends in the graduate student community. “Graduate students are so daring in their thinking,” says Martinez. “One is teaching a class in DNA replication and reached out to find out what could happen here.” Though the teaching fellow is based in the sciences, she is also an artist. “Graduate students have such varied interests and want to make connections for their undergraduates,” Martinez says. “They have ideas they want to communicate, and we can use art to make interesting associations that help their students think differently.”

Uncovering History

Raphael Koenig is the consummate connector with interdisciplinary interests. A native of Paris, he came to Harvard as a teaching assistant in French for the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, but soon decided to seek a PhD in comparative literature. “I love the comp lit department,” he says. “It’s versatile and open. You have so much freedom to pursue your interests.” For Koenig, this means advancing scholarship in outsider art—art produced by those without an academic or art school background. “For many modernists, this was art in its purest form,” Koenig explains, “and even if this idea is debatable, their interest was genuine and highly productive. It is a fascinating chapter in the history of modernism.”

In addition to speaking French and English (with proficiency in Yiddish and Chinese), Koenig is also fluent in German, a skill that the Harvard Art Museums needed for a cataloging project. “I am interested in Weimar Germany and took some amazing art history classes on the period,” he explains. “Then, an opportunity came up to research and catalogue archival materials related to the Bauhaus and its founder Walter Gropius.”

Walter Gropius came to Harvard from Germany in 1937, eventually rising to become dean of the Graduate School of Design. He arrived with his suitcases packed with materials from the Bauhaus, an informal archive he added to during his lifetime. He gave a treasure trove of visual materials to the Busch-Reisinger Museum, and his papers for the period from 1937 to 1969 to Houghton Library. “Gropius wanted to enshrine the legacy of the Bauhaus,” Koenig says. “So in 1947, Gropius and Charles L. Kuhn, one of the Monuments Men and the museum’s curator, called upon every Bauhaus artist they knew, saying, ‘Hey, do you have anything cool? Send it to us.’ And that’s what they did.”

A staggering number of artworks entered the collections, but several boxes of archival material laid in storage, uncataloged, for 30 years. Koenig was hired as a curatorial intern to inventory the archive. As he opened the first box, he knew he was looking at important documents that told the story of how Harvard came to hold one of the most significant collections of Bauhaus art outside of Germany.

Koenig’s work extends beyond the cataloging of the materials to determining ways to share them. “I’m currently assisting with a larger project at the museum to create a Bauhaus online research site and am putting together Internet resources that will help people connect with the collection online,” he says. “I’m also building an interactive tour of the Bauhaus-related monuments around Cambridge. And there’s a ton of them, including three on the Harvard campus.”

An Intellectual Activity

While many universities consider where the production of art fits within the academy, PhD candidates like Stephanie Spray embody what it means to meld creativity and scholarship. A student in the Department of Anthropology, Spray is pursuing a secondary field in critical media practice. “Harvard has been an exciting place to study thanks to the faculty, colleagues, and friends I’ve met through the Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL) and the Film Study Center (FSC), and because of the many opportunities to meet visiting filmmakers and artists at the Harvard Film Archive and the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts,” she says. “I was very fortunate to be at Harvard when the SEL was just beginning, since I found a place where art making is taken seriously as an intellectual activity, as a methodology for exploring and understanding the world, rather than as an addendum to academic pursuits.”

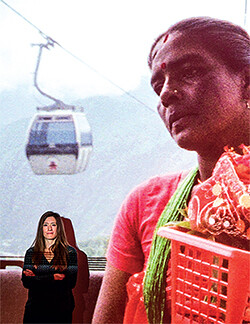

Spray leveraged her connections with SEL to codirect MANAKAMANA, a feature-length film shot entirely within a cable car taking pilgrims and tourists to and from the temple of the goddess Manakamana in Nepal. The film is composed of 11 shots, each one documenting the 10-minute ride of passengers in real time. The film won numerous awards during 2014, including Best Female-Directed Film at the Edinburgh International Film Festival and Best Director, Documentary, at the RiverRun International Film Festival.

“MANAKAMANA wouldn’t exist without the SEL and the FSC,” says Spray. “We received equipment loans from the FSC, as well as small grants to support travel and expenses on the ground. In fact, the 16 mm camera we used to shoot the film was the very same camera Robert Gardner, founder of the Film Study Center, used to shoot Forest of Bliss, a pivotal ethnographic film.”

Being a filmmaker and an anthropologist has enabled Spray to advance her scholarship in ways she couldn’t if she focused on one discipline. It also means that she can inspire others, too. “I had plenty of opportunities as a teaching fellow in film production and studio art classes in the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies, which further enriched my own skills as an artist,” she says. “I also developed the course ‘Compound Visions: Theory and Praxis of Sensory Ethnography’ for juniors in the Department of Anthropology.”

Spray is now completing her dissertation, which concerns the everyday lives and travails of the Nepalese musician caste who play a four-stringed instrument known as the sarangi. “I am interested in their custom of wandering—dulna jane—their meandering travel from town to town as they busk for money, food, or clothing,” she explains. “While it’s a concrete way of life for them, it’s also a beautiful metaphor for the work of filmmakers and anthropologists.”

The Cognitive Life of the University

In 2007, President Drew Gilpin Faust charged a Task Force for the Arts with evaluating Harvard’s efforts in the area. A year later, the Task Force released its vision for a 21st century education that would “educate and empower creative minds across all disciplines” in an effort to advance innovation. As a successor to the Brown Report, the Task Force for the Arts took their belief that students gain as much educational value from practicing the visual arts as they do from writing prose or poetry one step farther by recommending that the arts become “an integral part of the cognitive life of the University.”

It is a charge that falls on fertile ground. A scientist who uses art to explain DNA. An anthropologist who sees her field entwined with filmmaking. A comparative literature student uncovering the secret history of an arts movement. A ramp that connects the different experiences of art. People and places bridging the disciplines, with the arts firmly at the center.

Photos by David Salafia

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast