A Sound Approach to Women’s Health

Harvard Griffin GSAS Voices: Kimberly Lovie Murdaugh, SM ’13

Dr. Kimberly Lovie Murdaugh works to improve women’s healthcare using ultrasound technology. Murdaugh discusses her research on maternal and fetal health, her work with women who have undergone female genital mutilation, and how a chance encounter during her time at Harvard Griffin GSAS reaffirmed her commitment to translational medicine.

The Simple Act of Seeing

When I was a medical student, I learned that if you’re pregnant, your doctor will do an ultrasound to look at and measure the baby. But they don’t measure the placenta, which is a very important organ during pregnancy. It’s responsible for getting blood and nutrients from the mother to the baby. Sometimes the placenta is far too small to support the fetus, which can lead to stillbirths. In fact, around 60 percent of stillbirths are due to a small placenta.

I worked with Dr. Harvey Kliman at the Yale School of Medicine to study the relationship between placental size and infant birthweight. To do this, we measured estimated placental volume (EPV), an ultrasound method that Dr. Kliman developed in the hope of preventing stillbirths. A doctor who read our research and used EPV was able to prevent a stillbirth after detecting a small placenta; this prompted her to monitor the baby more closely, which revealed other abnormalities that probably would have gone undetected.

Another project that uses ultrasound has to do with helping survivors of female genital mutilation (FGM), which is still a practice in many countries. There are several types of FGM, but the most common involves cutting the clitoral glans, which is a small part of the whole organ. Since most of the clitoris is hidden beneath the skin, many people believe that the glans (the part we can see) is the entire organ. So for women whose glans has been cut, in their mind, their entire clitoris is gone. This greatly impacts the way they see themselves.

When men have sexual health issues, they can go to the doctor and get a penile ultrasound. But when women have similar concerns, doctors don’t offer clitoral ultrasounds; although this technique had been developed before, it had never made it out of research settings into the clinic. So I worked with a gynecologist, Dr. Amir Marashi, to develop the first clitoral ultrasound to be used in a clinical setting. Now, women who have undergone FGM can come to our clinic and receive an ultrasound. I use a trauma-informed approach to show them that, although the glans has been cut, most of the organ is still there, just under the skin. That simple act of seeing images of themselves often helps them feel more whole and complete.

A Caring Reminder

Harvard College was such a special place for me. When I was a freshman, half of our class was premed, and so was I. I was one of the few people who loved organic chemistry, so I decided to concentrate in chemistry. My junior year, I took an upper-level chemistry class on nanotechnology. I learned a lot from that experience, mainly that I wanted to go to graduate school to develop medical tools.

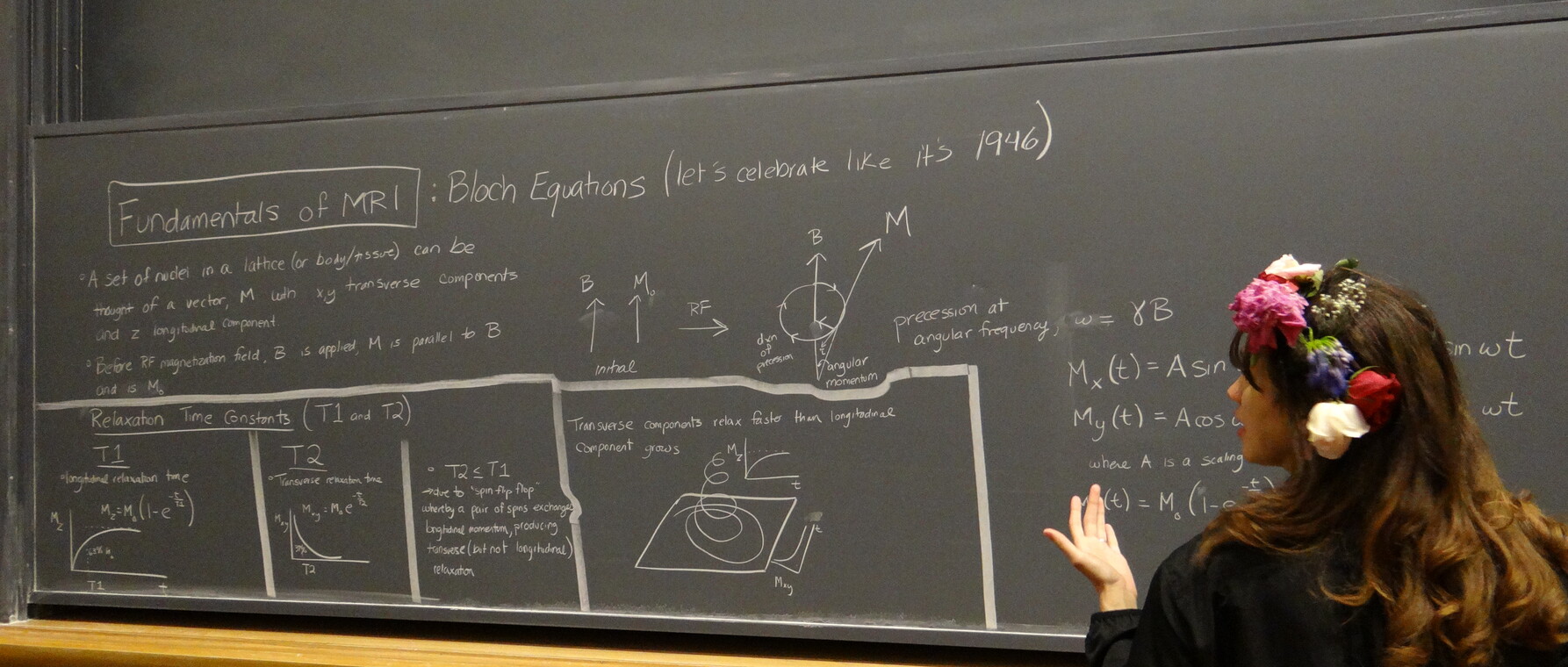

I enrolled at Harvard Griffin GSAS in 2011 to study engineering. It was there that I got a solid foundation in research and became an independent scientist. What I learned about physics, chemistry, and engineering gave me a huge advantage when I graduated and went on to Yale Medical School, where I fell in love with ultrasound and radiology and started down the path to the work I do now.

One day during my time at GSAS, I was coming home from the lab and saw there was a film screening at the Science Center. It was a new documentary on people living with HIV/AIDS in New York in the 1980s. Scientists were doing their best to develop antiretroviral medications, but the standard timeline for the FDA approval process wasn’t fast enough; so many people were dying. To make matters worse, women and people of color weren’t included in the research studies. The LGBTQ community joined together to form a group called ACT UP, and advanced HIV/AIDS research through protests and advocacy.

When I watched the film, I was moved by how the staff at the hospitals in New York took care of these patients when they needed it most. It reminded me why I wanted to go into medicine. It’s about getting the research from the lab to those who need it. At the end of the day, it’s about people.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast