The Secret Ingredient

The Challenge: Ask 4 teams of HILS students to make 3 dishes showcasing 2 types of miso in just under 2 hours. In the lab.

The secret ingredient: Aspergillus oryzae, a grain-loving fungus that under the microscope looks like a delicate flower on stem. Fermented with soybeans, grain, and, salt, it becomes miso paste, a staple of Japanese cuisine.

The challenge: Ask 4 teams of PhD students from across the 14 programs that make up Harvard Integrated Life Sciences (HILS) to make 3 dishes showcasing 2 types of miso in just under 2 hours.

In the lab.

It’s not unusual for HILS students to spend hours at the bench, except this time it was in Harvard’s cooking and science lab. Housed in the Northwest Science Building, the lab comes equipped with sauté pans and immersion blenders, pipettes and petri dishes.

The HILS Community Cooking Challenge, microbiology edition, was cooked up last year by Vayu Maini Rekdal and four co-organizers—Sam Carlson, Constantin Giurgiu, Alexa Jackson, and Alec Walker.

Bringing People Together

Rekdal, a second-year PhD student in Molecules, Cells, and Organisms (MCO), says he undertook his first science experiments in his childhood kitchen in Stockholm, Sweden, where he often cooked with his mother and learned that “cooking is a powerful way to bring people together.” Cooking brought him from Sweden to the US to work as a chef, which included a stint at Marcus Samuelsson’s restaurant Red Rooster in Harlem, known for its inventive take on classic comfort food. In New York, Rekdal found himself seeking new ways to enhance his cooking. “One of those ways,” he explains, “was science, which could provide new dimensions of flavor, texture, and sensations.”

But it wasn’t until Rekdal arrived at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, that his interests in science and cooking converged. “I fell in love with science because I saw the parallels between the kitchen and the lab: using your hands, multitasking, being creative,” he says. At Carlton, he majored in chemistry and biology and started Young Chefs, an educational program that uses cooking to teach science to school-aged children.

As a first-year HILS student, Rekdal was again drawn to cooking as a way of fostering community. “What we are trying to do with the cooking challenge is build community and also celebrate that we are all scientists,” Rekdal says. The cooking challenge was designed to encourage HILS students to “see their skills and experiences in a whole new context and recognize that the creativity and ingenuity from the science part of our lives reaches into the other parts of our lives.”

His co-organizers feel the same way. Jackson, a PhD student in chemical biology, says the catalyst for her interest in food was the joy and creativity that came from preparing and eating food with friends, which also intersects with her long-standing academic interests in nutrition, food systems, and access. For Giurgiu, a PhD student in chemistry, it’s all about the science. “I’ve always been interested in the chemistry of proteins and carbohydrates, which are the main constituents of food, alongside lipids,” he says. “I find the transformations these substances undergo during cooking fascinating.”

Last year, several of the organizing students attended a HILS dinner with Sheila Thomas, dean of academic programs and diversity at GSAS, who is a cancer biologist by training. In the course of their conversation, the idea of combining science and cooking came up. “I find the kitchen a different kind of experimental laboratory, and we began talking about how experiments are done in the kitchen,” remembers Thomas. “We then started talking about how a cooking competition could be a good way to bring students from across programs together.” Once the competition was announced, Thomas provided funding from HILS to support the event.

Cooking on a Deadline

Opening the competition, Harvard Medical School microbiologist Roberto Kolter gave a brief lecture on the microbiology of food. “As long as humans have been humans they have been using microbes in food and drink,” Kolter says. Microbes play an integral role in both food production and preservation, with flavor being one of the lucky side effects. The flavor and texture of bread, beer, wine, cheese, coffee, and chocolate, for example, all originate with microbial processes such as fermentation and acidification.

One particular microbe, known in Japanese as koji, is part of a family of microbes responsible for saccharifying fermentation, or the breakdown of starches into sugars. Classified as a fungus, Koji takes the starch in rice and other grains and breaks it down into sugars that can then be utilized by other microbes. It’s an essential ingredient in miso.

When fermented, different strains of the fungus grown on different grains—depending on time and the combination of ingredients—produce flavors ranging from salty, sweet, and fruity to earthy and savory. It’s the fermentation that gives miso what’s known as umami—one of the five essential tastes, alongside sweetness, sourness, bitterness, and saltiness—that translates roughly from Japanese as “deliciousness” or “pleasant savory taste.”

Walker, who is a PhD student in immunology, says the organizing committee chose miso as the secret ingredient because it is such a versatile ingredient that it would challenge teams to think outside the box and because it could star comfortably in both savory and sweet dishes.

Each team received portions of mild-flavored white miso, along with red miso, which is richer and more flavorful. The teams all drew from shared pantry staples to prepare their dishes, sourcing everything from a green grocer’s selection of vegetables to star anise and spicy kimchi.

Taste and Presentation

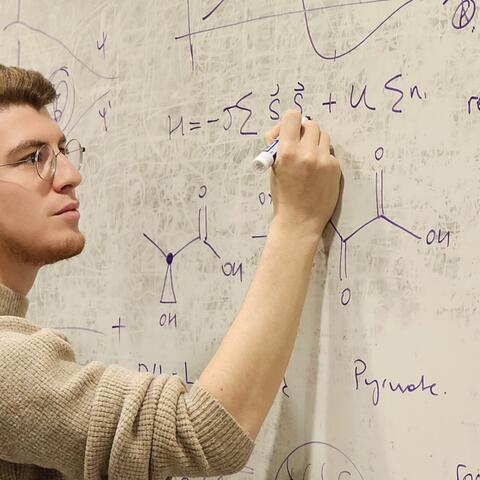

Then it was time to get to work. The contest called upon the qualities of top-notch scientists-in-training: teamwork, creativity, and a willingness to improvise. With the clock on countdown, the teams huddled to make their plans for cooking with white and red miso pastes. Their lab stations were stocked with both culinary and scientific tools, from pipettes to convection ovens, each just slightly bigger than a bread box.

The whimsically named all-woman team, Brie Coli, consisted of five students representing MCO and neuroscience. Viktoria Betin, Mallory Laboulaye, Dalila Ordoñez, Brenda Marin Rodriguez, and Martha Zepeda had sketched out their plan in advance. They were immediately poised to incorporate the secret ingredient into a menu of miniature vegetable flatbreads with mushroom, tomato and miso, a fruit salad of prickly pear, sweet bell peppers, peaches, and strawberries with a kombucha-miso-honey glaze and an apple-pear tart garnished with an apple rosette. Inspired by biofilms, they served their fruit salad in a petri dish.

The All Thyme Favorites, a team of second- and third-year PhD students in biophysics and biological and biomedical sciences (BBS), synthesized their collective cultural and culinary influences to design a menu that started with vegetable spring rolls served with a dipping sauce delivered in a conical Eppendorf tube, followed by empanadas with a fiery chipotle dipping sauce. They doubled-down on dessert, working miso into an almond-based halva, a traditional Indian dessert, topped with a miso glaze, a chocolate mousse, and a miso caramel candy.

A team of irreverent organismic and evolutionary biologists who dubbed themselves Darwin’s Deep Fried Finches whipped up an Asian-French–inspired menu of white miso–vegetable vichyssoise soup topped with a savory crust; a bean sprout salad with miso vinaigrette, topped with candied almonds, miso caramel and pomegranate seed, followed by a red-miso, kimchi ratatouille. In a nod to scientific ingenuity, Jennifer Austiff used a pipette to score her pie crust, creating a careful, decorative pattern. For dessert: a strawberry and star fruit custard-filled tart with caramelized miso glaze. Austiff, who loves the creativity involved in baking, says she was surprised and excited to discover how fun it was to improvise in the kitchen.

Meanwhile, the enigmatically-named Red Team’s Thomas Tullius made a quick pasta dough from scratch and then used a petri dish to cut out ravioli rounds. Jerry Wang engineered a filling of yogurt and eggplant, later poaching the ravioli over an induction hot plate. Then, in a nod to the scientific basis of modernist cuisine, he used a pipette to decorate a plate with beet puree before plating the single raviolo. Meanwhile, Jeroen Tas assembled a carefully constructed tower of grilled vegetables. As the clock counted down, the Red Team spun sugar into an extravagant garnish for their dessert of peach custard served with a chocolate miso and chile pepper-spiced mousse.

And the Winner Is…

Then came the moment of truth, as the teams presented their creations to an all-star panel of judges: HMS’s Roberto Kolter, Venkatesh Murthy from the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Ralph Mazitschek an assistant professor with the Chemical Biology PhD Program, and Sheila Thomas were joined with special guest Bob Yosses, the former White House pastry chef. Yosses was on campus to lecture on polymers and viscosity for the popular undergraduate course “Science and Cooking: From Haute Cuisine to the Science of Soft Matter.”

Before announcing the winner, Yosses remarked on each group’s culinary accomplishments in terms of taste, creativity, presentation, thematic cohesion, and their use of the secret ingredient. Darwin’s Deep Fried Finches, he says, set out an astute progression of the dishes and crafted a balanced custard with excellent flavor. Brie Coli’s apple cobbler, he remarked, was excellent, and he praised the creative use of the petri dish for serving their fruit salad. The judges loved the geometry and thematic cohesion of the Red Team’s dishes. The miso-chocolate dessert, he says, was one of the best examples of the miso being used to its full potential.

The win went to All Thyme Favorites. Yosses commended them for the way they embraced strong flavors, adapting both their cultural influences and the theme of microbiology into their dishes. Each team member was awarded a copy of Yosses’ book of his best desserts, The Perfect Finish: Special Desserts for Every Occasion.

Reflecting on their win, Christina Jayson, a PhD student in BBS, credited her team’s willingness to experiment and draw on their training in scientific thinking to respond to the day’s many culinary challenges. “We were troubleshooting the whole time. You do that in science as well,” she shares. “We essentially said, let’s do these dishes in parallel, one which we want to work, and meanwhile we are troubleshooting the backup, just in case.”

While the All Thyme Favorites were the favorites of the day, the excitement and enthusiasm for the first Community Cooking Challenge won the event. Rekdal and his co-organizers hope their experiment in community and cooking will be back next year.

Photos by Ralph Mazitschek

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast