Reframing the Landscape

Illuminating the way land is portrayed on film—and the relationship of filmmaking to the land.

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

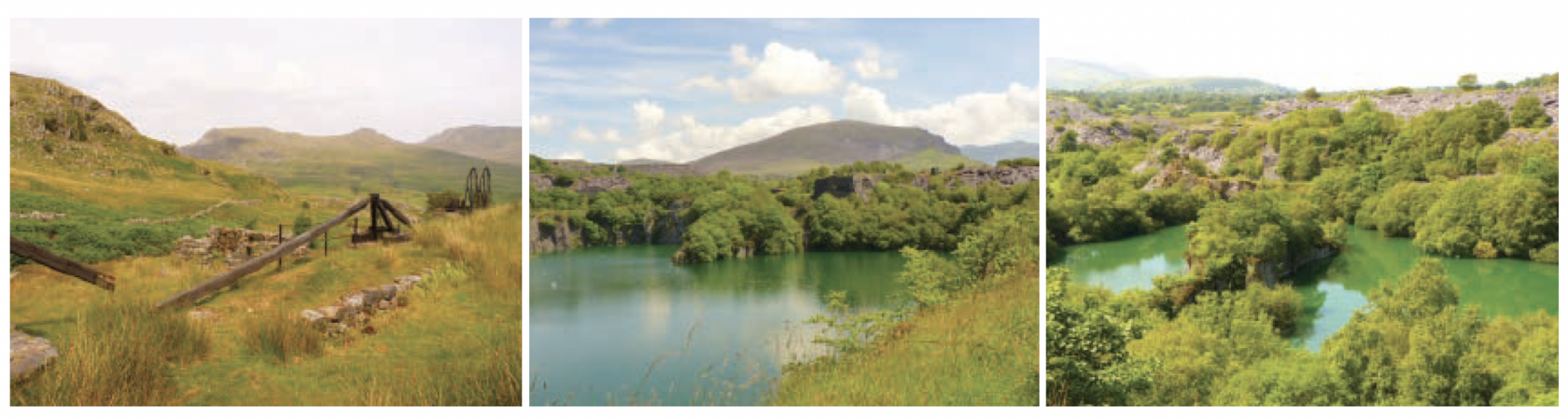

Becca Voelcker, PhD ’21, grew up in the Eryri region of Wales without a television. She didn’t need one. A national park, Eryri (or “Snowdonia” in English) is remote and rugged, bordered on the east by mountains and the west by the Irish Sea. Whenever she felt bored indoors, Voelcker would wander through the land. “It was a very free-range childhood,” she explains. “The landscape in Eryri is incredibly green and blue. It often resembles a painting.”

Voelcker didn’t have to walk far, however, to find sights that were much less idyllic. Right outside her house were huge mine shafts and quarry pits, some filled with water and so deep that divers would train in them—scars on the landscape left over from centuries of extractive industry. “Before I’d ever seen ‘extractivism’ in films and photographs, I’d seen it with my own eyes in the land in front of me,” she remembers. “All the 19th-century quarrying left mountains of slate waste across the landscape.”

A writer and historian of art, film, and visual culture, Voelcker looks underneath aesthetics to understand the politics, economics, and social history of extraction and change. Named a 2024 BBC New Generation Thinker by the British Broadcasting Corporation, Voelcker has recently completed her first book, Land Cinema in an Age of Extraction, which is forthcoming from the University of California Press. The book “unearths key examples of eco-political counterculture from the 1970s and tries to stimulate visual literacy amongst a generation of readers facing climate breakdown today.” At its heart is an engagement with land as an ecological, political, and aesthetic terrain.

A Global Conversation

Voelcker, who lectures in art and film history at Goldsmiths, University of London, coined the term “Land Cinema” to describe filmmaking that understands land as a locus of social and environmental responsibility, and film as a political tool. She sees the genre in conversation with Third Cinema, a movement of the 1960s and 1970s that rejected both a “first cinema” of Hollywood stereotypes and a “second cinema” of the elitist European avant-garde in favor of films that centered anti-colonial and working-class perspectives.

“Third Cinema is often made with or by the people doing the work of resistance themselves,” Voelcker says. “Land Cinema is very similar. It emerged during the 1970s, a decade marked by an acceleration in material extraction and increasing environmental consciousness, which drew in turn from feminist and anti-colonial understandings of justice. Land Cinema understands land as an intersection of ecological, political, and aesthetic issues.”

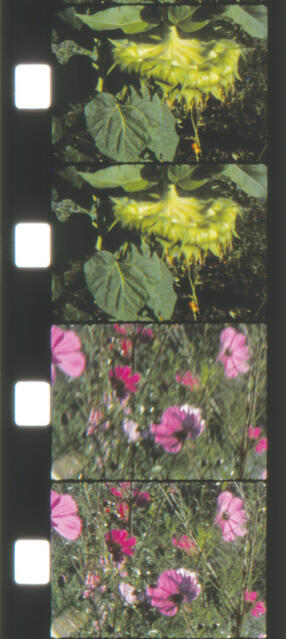

Voelcker underscores the global dimensions of Land Cinema with case studies from Japan, Mali, Colombia, North America, and Europe that explore shared but differential relationships to the problem of extraction. Along these lines, two of the many women artists considered in Voelcker’s feminist writing of history are the Navajo director Arlene Bowman and the Orkney filmmaker Margaret Tait. “Both women documented their experience of return to landscapes with which they had familial ties but from which they felt distanced,” she says. “Both films are ‘landscape-portraits’ of their makers, the land, and other women they meet there.”

Frustrated Idylls

In Navajo Talking Picture (1986), Bowman, the first Navajo woman to attend UCLA’s film program, returns to a reservation in northern Arizona to film a day in her grandmother’s life there. Bowman speaks no Navajo. Her grandmother doesn’t speak English and doesn’t want to be filmed. The resulting portrait is less than idyllic, which is why the film matters.

“This young woman with her camera wants to take—to extract really—her grandmother’s picture,” she says. “The grandmother says, ‘You don’t take our picture in this culture,’ and tells Bowman to stop following her. Bowman keeps that tension in the film, frustrating our desire for a lovely, straightforward, rural documentary about her relationship with her grandmother. In so doing, she invites the viewer to consider how she and her ancestors have long been portrayed in Hollywood Westerns that erase the diversity of culture and language among Indigenous people and speak nothing of settler colonialism or genocide.”

Margaret Tait had trained at film school in Rome and traveled around the world when she decided to return to the remote Scottish island of Orkney in 1968. Land Makar (1981) is Tait’s portrait of her neighbor, an independent woman farmer.

[I had] a very free range childhood. The landscape in Eryri is incredibly green and blue. It often resembles a painting.

– Becca Voelcker

Tait tries to bridge the gap in class and outlook by telling her neighbor that they are both “poets of the land,” Tait by filming it, and her neighbor by cultivating it. The neighbor is unimpressed. “What’s fascinating,” Voelcker says, “is that Tait retains this tension between herself and her subject in the film, just like Bowman did. There’s a feminist politics in this refusal of tidy narrative closures.”

Both Bowman and Tait’s films are shot in landscapes of rugged beauty. Both confound the viewer’s expectations by portraying difficult encounters between two generations and between these insiders and outsiders. Both ask us to look back into film and art history to think about how the land—and its people—have been portrayed in the past.

“In Tait’s film, for example, we might think of the 18th-century landscape tradition, when these idylls were painted,” Voelcker says. “They were commissioned by landowners who had made their fortune in the transatlantic slave trade. Returning from the Americas, they cleared citizens from land kept as commons for centuries to make way for privately owned sheep pasture serving the wool trade. They painted their newly enclosed landscape in a picturesque aesthetic, but in fact, it was a site of violence. Tait’s filmmaking in Orkney invites us to consider this historical aesthetic and its political implications.”

Collective Action

In addition to individual filmmakers like Bowman and Tait, Voelcker studies collectives like the one established in Paris during the 1970s by Bouba Touré and more than a dozen of his fellow West Africans. In France, the members of the group had endured poor living and working conditions as well as racism. When drought hit the Sahel region of Africa, the migrants’ starving families wrote to say that nothing would grow, not only because of the weather but also due to years of colonial plantation agriculture that had depleted the land. So, the group of 14 workers gave up their factory jobs, went back to their homeland, and established the cooperative Somankidi Coura farm community to help sustain themselves.

Voelcker says that the farm, still in operation with over 300 members, combined self-sufficiency with self-representation. “The thing that fascinates me about the collective is that they used cameras from the minute they began this project,” she says. “They were filming themselves, photographing themselves to document what was going on. As they were learning about irrigation and biodiversity, they were also producing their own stories, their own perspectives.”

For the Malian collective, filmmaking was itself an act of transgression. “French colonizers had prohibited their West African subjects from even using a camera,” Voelcker notes.

Touré also literally transgressed national boundaries, smuggling seeds, ideas, photographs, and energy from one continent to another. “He was showing that these geographies are fundamentally connected,” Voelcker says. “It’s another example of a filmmaker thinking about their own perspective as it relates to others and communicating this relation through film.”

University College London Professor Kristy Sinclair Dootson, a fellow BBC New Generation Thinker, says that Voelcker’s work is driven by a series of questions: how can we rethink the ethics of making images of nature in an age of climate crisis? How can artists reposition themselves in relation to the land in a responsible and care-driven, rather than extractive, way? And how can viewers learn to see and think differently about their social and physical surroundings?

“That Becca’s work spans so many different geographic areas and types of artistic practice is not merely impressive, but a testament to how pressing these issues are for artists and audiences,” Dootson says. “Becca’s capacity to engage audiences with these urgent issues has been recognized with her appointment as a BBC New Generation Thinker, confirming her special capacities to explain complex ideas in plain language and through compelling storytelling.”

Wounded Land

While the term “Land Cinema” may conjure up visions of rural, verdant landscapes, Voelcker notes that most of the world’s population lives in cities. Here her work is influenced by the thinking of First Nations theorist and activist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, who argues that humanity should care for and about “wounded land” as well as that which is pristine, beautiful, and green.

“There’s so much talk now of ventures that offset carbon emissions with planting monoculture forestry—usually in the Global South,” Voelcker explains. “It’s a way of repeating age-old cycles of colonial power differentials. By looking at damaged land, we’re saying that we can’t just push things to another place and only look at green spaces that we have successfully rewilded in London, say, or Boston. Those initiatives are great but focusing only on them misses the full picture.”

In search of a fuller picture, Voelcker returned to Japan, where she had lived before Harvard. There, she researched a group of radical filmmakers, activists, and photographers in Tokyo who pioneered a new way of looking at urban environments during the 1970s. Through grainy black-and-white photographs and experimental films, the artists depicted the “economic miracle” of postwar Japan as a blur of concrete, traffic, and pollution. “They called it fukeiron, which means ‘landscape theory,’” Voelcker says. “At the time Japan was promoting itself as this epicenter of technological advancement and growth. These images produced on film and also in some interesting essays presented the fallout from this progress, which might have been good for GDP but not for the Earth, the farmers, and citizens of the land.”

Landscape for the fukeiron filmmakers and photographers was not green or pastoral; it was a diagram of socioeconomic and political power. “They filmed it like it was a crime scene,” Voelcker says.

“The whole of Japan had been transformed into copies of Tokyo, controlling and regulating everyone.” University of Cambridge Professor Victoria Young, a scholar of modern and contemporary Japanese literature and Japanese cinema, says Voelcker’s approach is fascinating because it makes connections that may not at first seem organic or obvious. “Becca’s work draws from different sources and materials to create a resonant and self-reflexive approach to scholarship,” Young says. “However, as her explorations root themselves in the land and the ravages that modern life have wrought upon it, they also bear witness to a universal fate whose multiple inflections are far from contrasting but rather, offer multiple responses that are each, equally vital for understanding the problem of environmental collapse and for laying the groundwork towards—perhaps, one hopes—future, possible solutions.”

By looking at damaged land, we’re saying that we can’t just push things to another place and only look at green spaces that we have successfully rewilded in London, say, or Boston. Those initiatives are great but focusing only on them misses the full picture.

– Becca Voelcker

Back to the Cinema

Collectively, Voelcker’s diverse cinematic explorations speak to the need for a multifaceted understanding of land, identity, and power. Her work, grounded in a personal narrative of place and history, offers new insights into filmmaking as an act of resistance and reclamation. Writing Land Cinema became both a scholarly endeavor and a journey to reconcile her own position within the broader landscape of social justice.

“The more I delved into these films, the more I reflected on my upbringing in Wales,” she confides. “Attending a monthly film screening of world cinema organized by volunteers in a local cinema inspired a lifelong intrigue with how different cultures picture ‘us’ and how they relate to the land they inhabit. Later, the Harvard Film Archive became a second home for me, its treasure of films opening my eyes to many more cultures and ways of seeing.”

In that context, it’s no surprise, perhaps, that Voelcker’s next book project, tentatively titled A History of Us in Images, turns to the complexities of identity and belonging. At a time of stark cultural divides and the need for collective climate action, she asks the pressing question: What does “we” mean?

Dr. Edgar Schmitz, director of the MPhil/PhD Art Research Programme in the Department of Art at Goldsmiths, says that his colleague’s work is broadening the reach of their department’s expertise, becoming an important reference point for other forward-thinking work. “Becca’s intimate knowledge of historical and current practices at the intersection of aesthetics and activism, as well as her detailed understanding of East Asia in particular, have allowed us to host research in those fields that we would otherwise simply not be able to support adequately,” he says. “Her work resonates deeply with ongoing staff research in art and ecology, climate justice and filmic aesthetics, and is already having a profound impact on our teaching across undergraduate, postgraduate-taught, and doctoral programs.”

Through her work, Voelcker not only critiques historical and cinematic narratives but also provides a vital toolset for interpreting contemporary visual culture. Her exploration offers a tableau for understanding how images shape our worldviews, and how storytelling can unravel or reinforce existing power structures. Land Cinema precedes a moment of global reflection, prompting readers to see the world—and their place within it—through a lens of informed empathy and critical inquiry.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast