No More Elegies

Research reveals forces driving opioid deaths—and the best ways to intervene

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

Travis Donahoe looked up to his grandfather as a boy growing up in Wayne County, West Virginia. In turn, “Pawpaw” doted on his first grandchild. The recently retired man, who was deeply involved in his church community and a founding member of the local chapter of Habitat for Humanity, often took his grandson fishing and spent time with him at the family cabin built amid the rivers, trees, and mountains of the Monongahela National Forest. So, when he was ten years old and his grandfather died suddenly from a heart condition at age 55, Donahoe was heartbroken. When he arrived at the funeral, however, he found he was far from alone.

“It seemed like the entire county was there,” he said. “Everyone was so upset by my grandfather’s death and so supportive of me and my family. Even now, I'll go back home all these years later and run into people who talk about him and remember him positively. That was the closeness of the community I grew up in, and it has really stuck with me as a reminder of how fortunate I am to have grown up in that environment and the importance of giving back.”

Over the last three decades, Donahoe’s community—and many more like it across Appalachia—have been devastated by an opioid epidemic that has taken the lives of thousands. Inspired by his love for his home and the people there, he studies the epidemic, its impact, and the most effective ways to address it. A PhD graduate of Harvard's Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Harvard Griffin GSAS) and now a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, Donahoe finds that enforcement actions targeting suppliers that profit from the opioid crisis, rather than the vulnerable individuals swept up in it, are a critical way to stem the tide of addiction and death.

A Thirty-Year Tornado

Donahoe says that over 750,000 Americans have died from opioid overdoses since 1990, with over 80,000 deaths annually in recent years. Moreover, he says the statistics probably underestimate the number of dead due to inaccuracies in toxicology reporting. “A lot of times, a person will overdose and the coroners won't test for a specific substance,” he says. “So, in the national vital records, it will be tallied simply as a drug overdose death. There have been more than 1.3 million of those since the mid-90s. Based on the best estimates in the literature, close to 1 million of them were likely due to opioids.”

The crisis began in the mid-90s with prescription opioids like oxycodone and hydrocodone, then migrated to heroin, and illicitly manufactured fentanyl starting in 2012. Communities in Appalachia were hit particularly hard as many labored in occupations like mining and manufacturing, where they were more likely to experience chronic pain. “Drug overdose is a major contributor to recent reductions in life expectancy, reversing a decades-long trend,” says Donahoe’s University of Pittsburgh colleague, Professor Julie Donohue, chair of the school’s Department of Health Policy and Management. “People with low educational attainment, a common measure of socioeconomic status, have experienced a disproportionate burden of overdose death in ways that mirror other health problems but are poorly understood.”

There have been more than 1.3 million [drug overdose deaths] since the mid-90s. Based on the best estimates in the literature, close to 1 million of them were likely due to opioids.

–Travis Donahoe

Pharmaceutical companies took advantage. Firms like Purdue Pharmaceuticals drew up maps of areas with high levels of patients suffering from conditions that could lead their doctors to prescribe opioids, then sent sales representatives to close the deal. A lack of access to treatment compounded the problem. “Rural communities often don't have many primary care physicians or nurse practitioners, much less the kinds of places that can prescribe and manage medications people would need for effectively treating opioid use disorders,” Donahoe says. Donahoe’s ongoing research shows state policies also made things worse. “West Virginia, for example, has a moratorium that goes back to the mid-2000s on new opioid treatment programs, which are the only clinical settings where patients can get methadone, one of the few medications that are effective for treating opioid use disorder. You can't open a new program in the entire state, and recent proposals have sought to close down all of the existing ones.”

Harvard Professor David Cutler, one of Donahoe’s PhD advisers, says that, alongside COVID-19, the opioid epidemic is one of the most important public health crises of our time. “It has hit many parts of the US—including Appalachia, but also areas such as Massachusetts and, increasingly, the West Coast—like a tornado. No area in its wake has been spared.” Donahoe says the devastation of the epidemic extends well beyond the number of dead and sick. “Opioid addiction causes a host of significant trauma to people who are addicted, as well as their families, and ultimately the kind of close-knit communities I grew up in.”

Supply Side Interventions

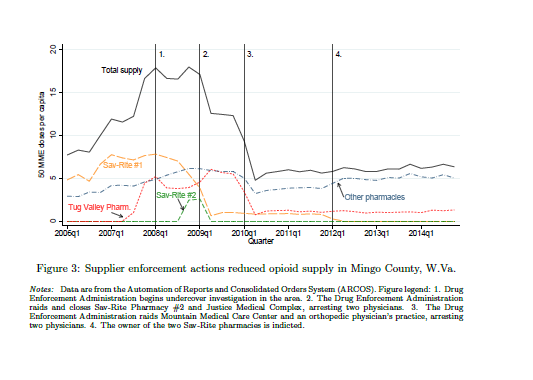

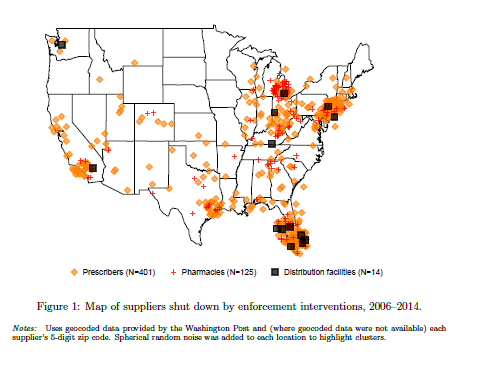

For his PhD dissertation at Harvard Griffin GSAS, Donahoe explored the impact of law enforcement on the opioid epidemic. He collected data on 540 publicly reported enforcement actions in the prescription opioid market undertaken nationwide by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) from 2006 to 2014. Significantly, the targets of the interventions were suppliers rather than sufferers—doctors and pharmacies that were excessively prescribing and providing opioids.

“Often, the pharmacy shut down would be the only one that would accept patients from one of these high-volume prescribers, who were writing prescriptions for millions of opioids in a small town,” he explains. “Then there were about 15 distribution facilities that were shut down for supplying the high-volume pharmacies, not following their federal obligations under the Controlled Substances Act to report suspicious behavior to the DEA.”

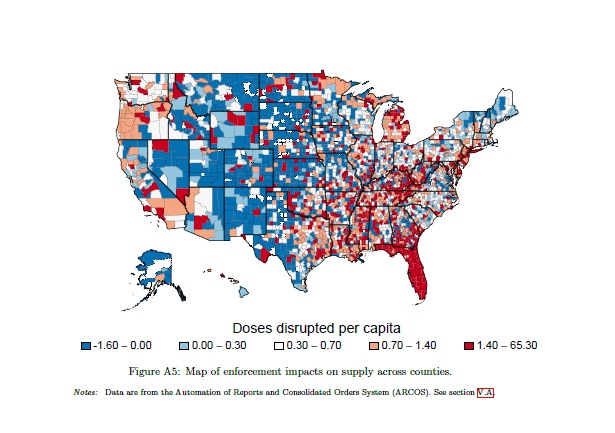

There was some concern among health policy economists about whether these sorts of interventions would be effective, or worse, even exacerbate the epidemic. In a competitive market, other pharmacies and distributors might fill the gap created by those shut down by federal officials. Opioid consumers might move on to different, more dangerous drugs like heroin. On balance, however, Donahoe found that enforcement efforts targeting suppliers were effective.

“It turned out that, if you shut down one of these worst-acting pharmacies, no other fills in,” he says. “These actions sent a signal to other pharmacies in the market that they could lose their license or get tied up in an investigation. So, whatever quantity of opioids the bad actors would have been dispensing was a loss in the market.”

Donahoe is quick to point out that some consumers may well have substituted heroin or fentanyl for discontinued prescription drugs. But the net result of the enforcement was positive. “A patient who is addicted to prescription opioids and suddenly loses access, that’s the kind of patient who may turn to heroin or illicit fentanyl. But someone who’s misusing them recreationally . . . enforcement can keep them from overdosing or becoming addicted and switching to heroin or fentanyl down the line.”

In all, Donahoe found that each intervention on average prevented around 11 deaths, or about 6,000 lives saved nationally from 2006 to 2014. “These did not end the opioid epidemic, but they had very high public health benefits from the standpoint of cost, effectiveness, and other standard measures of impact.”

Cutler says Donahoe’s research methodology was rigorous and calls his findings “exceptionally strong.” “Travis’s results will be the standard in the field,” he says. “It is not possible to understand routes to addressing the opioid epidemic without incorporating his work.”

Minding the Gap

At the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, Donahoe continues to study the opioid crisis. His colleague, Professor Donohue, says that, despite substantial investments in research, questions remain about the role of different drivers of the epidemic. “For example, how much was an issue of supply versus demand?” she asks. “Among demand-related factors, there are myriad explanations at the individual and community level. Travis’s work will help us to tease that apart.”

Donahoe says that the big driver of the opioid epidemic today is illicitly manufactured fentanyl. The drug first took hold in cities like Boston and New York, moving south and west from there. “Fentanyl became available in different states at different times with different impacts that aren’t yet understood,” Donahoe says. “How does the drug impact neighborhoods that have high economic distress compared to those that are wealthier or have better access to healthcare? Within that context, which policies and treatments were most effective? How are they hitting the most vulnerable populations at the highest baseline rate of opioid mortality?”

Currently under consideration by the National Institutes of Health, Donahoe’s new grant proposal would leverage the data linkage between the national Mortality Disparities in American Communities (MDAC) study and the US Census’s annual American Community Survey, which provides information about an individual’s neighborhood, access to health care, living situation, and a wide variety of social and economic indicators that can be linked to mortality outcomes.

“The data that researchers have worked with to study local drivers of the opioid epidemic are things like county-level mortality rates,” Donahoe says. “But think about how much heterogeneity there is within any given county in the US. I mean, in Pittsburgh, you have places like Shadyside and Fox Chapel, which are wealthy neighborhoods with mansions and high-income physicians and university faculty living there. But in the same county, you have places like Braddock and McKeesport, which have been among the most impacted communities by declining steel manufacturing employment in the US, and more than one-third of people are living below the poverty line. So, the goal of my project is to increase our understanding of the structural drivers of the opioid epidemic at a very local level in ways that the literature hasn’t done to date.”

Travis’s results will be the standard in the field. It is not possible to understand routes to addressing the opioid epidemic without incorporating his work.

– Professor David Cutler

It is the second part of Donahoe’s project, however, about which he is most excited. In it, he plans to take his more fine-grained data to community leaders, policymakers, and public health officials in affected communities to show them the factors that are predictive of opioid mortality. “They’ll be able to see the key drivers in their communities,” he says. “Then I will engage them in a structured process to co-develop specific interventions that would address these drivers, as well as be feasible and sustainable locally.”

Harvard’s Cutler notes that settlements between local governments and various opioid manufacturers, distributors, and dispensers have made over $50B available to address the opioid epidemic. In that context, Donahoe’s research can have a big impact on millions of Americans.

“There are many, many valuable uses of the settlement money,” he says. “They include more treatment facilities, greater use of harm reduction strategies, and targeted interventions to reduce prescribing. Travis’s research provides an empirical basis for localities to choose how to intervene. This is vital because we cannot afford to waste money or time on solutions that will turn out to be ineffective.”

The overarching goal of Donahoe’s project is to understand the distribution of opioid risk in the US: who is most vulnerable, where they are, and what policies and interventions are most helpful. A larger personal goal, however, is to humanize those caught up in the epidemic and to treat them and their suffering with the dignity they deserve.

“There is a long history of people in elite communities looking down on rural people,” he says. “I do think that it enabled people with the power to change things to overlook the significant harm that was taking place. There are actually records of pharmaceutical executives mocking people in places like West Virginia and Kentucky for being addicted to the opioids they were selling. Ending this epidemic is one of the most important changes we can make to improve the health—and dignity—of all Americans.”

Travis Donahoe's PhD research was supported by multiple grants from the National Institutes of Health, including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Aging.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast