A New Standard of Care

How governments might redefine and support the well-being of children and families

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

“I’ve always loved political theory,” says Emma Ebowe, a PhD candidate in government at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, “and I’ve always found it beautiful and important to think through ethical questions about how we live together.” After graduating high school, Ebowe worked on welfare reform in the United Kingdom. Her job took her around the UK, connecting her with civil servants, consultants, and computer programmers. But amongst all the important work she saw, Ebowe noticed how few of her colleagues talked about values. “Meeting the many challenges of implementing policy reform was so hard, there seemed to be little space to talk about the vision of well-being and justice these reforms were trying to support.” These questions led Ebowe to the academic study of government, and she began her PhD with the broad goal of studying the idea of the welfare state and its impacts on families and communities in the US and UK.

Ebowe’s research interests quickly took on timely importance. Soon after starting her PhD program in the fall of 2019, Ebowe witnessed how the COVID-19 pandemic drastically disrupted social and community life. She saw how the pandemic revealed social inequities––especially for marginalized communities and families with children––and, in the 2020 protests following George Floyd’s murder, she welcomed the emergence of new public discourses about the role of government agencies. Social movements that called to “Defund the Police” sparked widespread conversations about the intended goals of public institutions. But Ebowe noticed that there was relatively less discussion about the values expressed by other kinds of welfare infrastructure.

“People were calling to ‘defund the police’ and ‘fund social work,’” she reflects, “but there were still ethical questions missing from the conversation, like: what kind of social work to support, what social work should aim to do, and what moral problems are associated with contemporary social work.” Ebowe herself grew up in the UK as the daughter of a single parent. Her childhood experiences with her own social worker were her first introduction to the welfare state. “I learned a lot about how the system functions,” she says. “It left me with the sense that state agents can pry and intrude into people’s lives in ways that are unfair, even as they also provide deeply important forms of material support.”

Today, these personal experiences inspire Ebowe’s dissertation research on the contemporary foster care system and her broader interest in studying how government institutions impact families and children. Her work challenges common assumptions by uncovering and critiquing ethical issues in government institutions designed to protect child welfare in the United States and United Kingdom. Through her critical study of the foster system, Ebowe also addresses larger questions about the role of the state in intimate family life, how to best support those in need, and how social service institutions could better work toward social justice.

Investigating Inequitably

The government institutions that protect child welfare in the US impact a larger proportion of our population than many of us realize. Recent research shows that over one-third of American children experience an investigation by Child Protective Services (CPS) before turning eighteen. These proceedings disproportionately affect marginalized communities, with notably higher prevalence among Black, Indigenous, and low-income families. Many of these investigations do not lead to findings of child neglect or abuse––but when they do, CPS may order that a child be removed from their home and placed elsewhere, either with relatives or in a foster home.

In 2020, around one in ten children entered the US foster system because they lacked adequate housing, and evidence shows that when poor families receive even modest increases in financial support ($100 on average), they are less likely to be involved in the foster system.

—Emma Ebowe

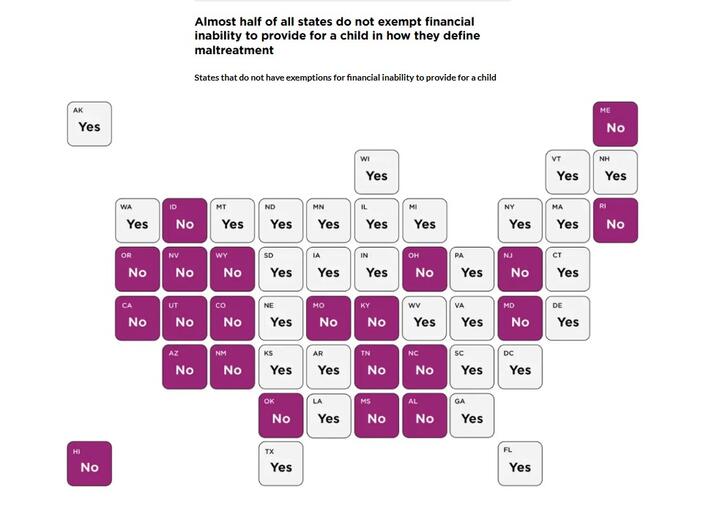

While this response purportedly aims to ensure the child’s safety and well-being, removing a child from their parents and home can be disruptive and upsetting. The institutions with the power to make these decisions need fair procedures to determine when this drastic measure is necessary. In many situations, for example, severe poverty can lead to a child being removed from an otherwise loving home––with the consequence that families in economically marginalized groups are more likely to be broken apart by this system. Almost half of all U.S. states do not exempt a caregiver’s financial inability to provide for a child from legal definitions of child neglect, drastically aggravating this problem.

“The foster system often impacts poor families who may not need to be separated,” Ebowe explains. “In 2020, around one in ten children entered the US foster system because they lacked adequate housing, and evidence shows that when poor families receive even modest increases in financial support ($100 on average), they are less likely to be involved in the foster system.”

Ebowe highlights that the government’s child safeguarding procedures can also perpetuate existing racial and ethnic inequalities. “There’s compelling evidence of racial discrimination in the US foster system,” she explains, “including through CPS call agents, who are more likely to escalate calls after reports of child welfare concerns in Black families than in comparable white families.” Ebowe’s work illustrates how racist beliefs and the individual biases of state agents can lead to discrimination against Black families, resulting in more Black children being removed from parental custody.

Relief, Not Removal

An alternative approach to the problem, proposes Ebowe, is to prioritize a more holistic conception of child and community well-being. Ebowe’s work re-emphasizes the moral value of relationships specifically within racialized families and families living in poverty, who are disproportionately impacted by child removal procedures. Her scholarship is guided by the principle that the relationships within poor and racialized families are just as valuable as those within other families, and she maintains that poverty alone should not justify foster system intervention into family relationships––even though statistics show that it frequently does.

In her PhD dissertation, Ebowe takes an approach to the US foster system that is grounded in her study of political theory and moral philosophy. Drawing on empirical evidence to inform her philosophical arguments, she analyzes existing child welfare policies in terms of their impacts and the ethical principles implicit within them. “If you think about it,” she says, “it’s such a strange idea that a child’s well-being would be just about their material or economic well-being and not also their relational well-being—their family relationships and their communities. By conflating poverty with maltreatment, our policies, laws, and infrastructure set up this supposed trade-off between a child’s relational well-being and their chance to have secure housing or a financially stable upbringing.” Children who are removed from parents because of poverty, for instance, may gain stable housing, or more financial support, but at the cost of their relationship with their parent.

[Ebowe] offers a highly original, compelling treatment of an institution with great power over the lives of children and families, especially poor children and families, as well as a new path forward.

—Professor Danielle Allen

To Ebowe, this kind of disruption to our most valuable relationships is underacknowledged in political theory. In response, she theorizes a concept she calls “relational violence” to describe the power of an external force––like the foster system––to disrupt a close relationship and damage an intimate bond, such as that between a parent and child. Conventional accounts of the state’s coercive power focus on its capacity for physical violence and force. Ebowe alerts us also to the state’s capacity to disrupt relationships.

“Although this is sometimes justified––in cases of physical abuse, for example,” Ebowe argues, “the intimate harms of relational violence explain why the state is unjust when it removes children in cases where there is an equally effective, but less disruptive option.” In this view, the government could act more justly by prioritizing supportive welfare interventions that keep families together, rather than defaulting to the removal of a child to address instances of housing insecurity or financial poverty.

This work represents a novel way of using political theory and moral philosophy to address pressing contemporary problems, according to James Bryant Conant University Professor Danielle Allen, Ebowe’s dissertation advisor. “Emma’s dissertation is a first-rate example of applied political theory, combining normative political theory and public policy analysis,” Allen says. Ebowe’s theories and concepts allow her “to provide concrete characterizations of injustices in contemporary foster care systems and to develop policy alternatives. She offers a highly original, compelling treatment of an institution with great power over the lives of children and families, especially poor children and families, as well as a new path forward.”

Toward a New Notion of Care

Ebowe has also explored the potential of holistic and community-based care structures through her involvement in Harvard’s undergraduate house system as a resident tutor in Quincy House. As the house’s faculty dean, Professor Eric Beerbohm, explains, “Emma’s theorizing has informed her practice as a tutor,” which is marked by strong relationships with students and “speaks to her commitment to the pastoral care of our community.” Her work in the house has prioritized relational well-being through advising and education on consent and relationship topics for members of Quincy House and tailored programming specifically to support BGLTQ+ students.

In addition, Ebowe enjoys thinking through various possibilities of what state support for families and household care systems can look like––including ideas like community-based group housing, or birth certificates listing grandparents or alternative caregivers in addition to biological parents. “There are various ways the state might better support our most valuable relationships,” she says, “and I’m excited to think creatively about all of them.”

Ebowe hopes her research and analysis of the foster system will have long-lasting impacts within and beyond the academic world in three ways: she aims to raise broader awareness of injustice in the foster system; she wants to disrupt assumptions that removing children is itself always care and draw attention to the harm it causes—even when it seems justified; and she hopes to get policymakers and the public to take more seriously the idea that child welfare is relational as well as material, and that all children and families deserve the same respect.

“We need a richer notion of what well-being means for families and children,” she says. “The welfare state is full of complex moral questions about how the same intervention could both harm and help the same people. My work on the foster system is only one small part of this broader conversation.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast