More Is More

Becca Rothfeld writes "in praise of excess"

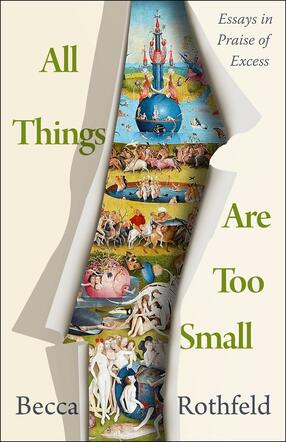

Currently on hiatus from Harvard Griffin GSAS, philosophy PhD candidate Becca Rothfeld is the non-fiction book critic of the Washington Post. The winner of the 2023 National Book Critics Circle Award for Excellence in Reviewing, Rothfeld has contributed essays and reviews to publications including the New York Times Book Review, The New Yorker, and The Atlantic. In her new book, All Things Are Too Small, Rothfeld pushes back on what she sees as our culture’s embrace of minimalism and argues that it leaves us creatively and spiritually impoverished. In advance of her appearance at Harvard Book Store on April 3, Rothfeld spoke with Harvard Griffin GSAS Communications about her disdain for tidying expert Marie Kondo and for Christopher Nolan’s film, The Dark Knight Rises; the need for egalitarianism in economics but not in art or relationships; and how favoritism often goes hand-in-hand with love.

Marie Kondo is kind of a bête noire in your book. What's your beef with her?

I live in a house full of books, none of which I intend to discard, and Marie Kondo advises—I kid you not—that we cut the sentences we like out of books and paste them into an album so that we can save shelf space. It's criminal!

On a more serious note, although it is seriously demented to mutilate books in the interest of having a depressingly empty house, not just Kondo but many of her colleagues in the world of professional tidying—I read more decluttering manifestos than I care to recall as research for this book—urge their followers to ask themselves, “Do I want this, or do I need this?” And then they tell us to keep only what we need. But why shouldn't we keep more than we need? Bare survival isn't enough. You may not need your entanglements and encumberments to subsist from one day to the next, but they make you the person you are—and many of your possessions are physical manifestations of your entanglements and encumberments.

How are the movies Troll 2 and The Dark Knight Rises—and the Twitter campaign to “let people enjoy things”—exemplars of misplaced egalitarianism?

I argue in the book that we get matters backward: Having failed to equalize economic resources, which we really ought to be equalizing, we try to equalize cultural prestige, which can't and shouldn't be equalized. Hence the memeified maxim, "let people enjoy things," which is bandied about online to silence critiques of popular cultural artifacts like The Dark Knight.

You mention equalizing resources. In the book, you talk about economic justice in relation to the kind of excess from which creativity flows. What's the link?

One of the guiding ideas of my book is that members of a polity are entitled to roughly equal shares of resources, but they are not entitled to equal shares of esteem or affection. It's an injustice if someone has five vacation homes and someone else barely has enough to get by; it's not an injustice if I judge one artwork better than another, or if I love one person and hate someone else. Our society is very inegalitarian economically, and in a misguided attempt to compensate, we tend to insist on cultural equality. But, as I say in the book, democratizing culture will not democratize politics. Even if we succeeded in bullying people into saying that, say, Marvel movies are great works of cinema, that wouldn't get any of Elon Musk's money into my pockets.

But there is an important relationship between economic justice and the production and appreciation of good art. As I put it in the book, "talented people would be less frequently stymied and have more opportunities to hone their gifts. Aesthetic culture as a whole would improve if audiences had the time and the education to cultivate their tastes." In other words, the artistic and romantic domains wouldn't become egalitarian in terms of outcomes, but they would become egalitarian in terms of access.

A college friend and I had a bit of a row over Get Back, Peter Jackson’s eight-hour Apple TV documentary about the Beatles. She and her husband watched the whole thing multiple times, delighted by the realistic presentation of how the creative process unfolds. I bailed after four hours of watching John, Paul, George, and Ringo smoke, chat, and generally mess around. Have I fallen prey to the poverty of smallness?

I have not seen the film, but I know first-hand that not all big things are good. A Little Life is one of the longest contemporary novels in recent memory, and also one of the worst, in my opinion. And of course, bigness of the sort I recommend needn't be a matter of size or length. The kind of extravagance I favor is a matter of gratuity. It's wholly possible for a very long movie to have a spare and deflated aesthetic, to resist the opulence of unnecessary flourishes. By the same lights, it's possible for a short movie to be excessive in some sense, either because it's packed with luxuriant imagery or because its content is overflowing. Case in point: Werner Herzog's 45-minute documentary, The Dark Glow of the Mountains, about a mountaineer's obsessive quest to scale the highest peaks in the Himalayas for no reason at all. It's a wonderfully excessive film.

You write that “In a world of absolute equality . . . there would be no place for love, which is nothing more or less than favoritism par excellence.” Of which kind of love are you speaking? Don’t many of the world’s religious traditions teach exactly the opposite—to love without favoritism?

Of course, there is a different sort of love—the sort of love that, for instance, Jesus bears towards everyone. (Or so I think; I'm Jewish, so I'm no expert.) Surely there is value in regarding everyone as equals in some fundamental respect, but we shouldn't cherish everyone equally in every respect. We would be entirely different creatures if this dispassionate love were the only sort of which we were capable. The word "friend" would be meaningless if there weren't some people we preferred over others. What kind of a bloodless existence would that be?

Finally, to what extent is the book’s title, All Things Are Too Small, and approach, a “praise of excess,” provocations to get readers to reflect on the gorgeous messiness of the human condition? Is that your hope for the book?

I suppose in a way it is! I'm not sure I'd put it that way, though. I'd say that the book mounts different arguments for the idea that various sorts of gratuities—the clutter in our houses, the obsessions that crowd our minds, and so on—make us the people we are and are therefore valuable.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast