Intangible Benefit

Multi-industry corporations invest in ideas that benefit their global enterprise. But old-school tariffs are poised to impact their bottom line.

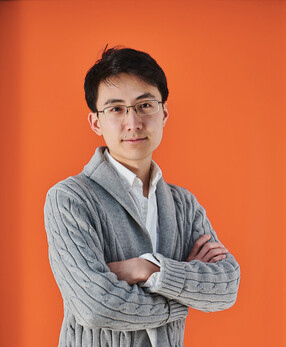

Whether they are targeting soybeans or dishwashers, computers or cheese, tariffs—once the minutiae of treaties—are making headlines. Traditionally levied to counter other economic factors, tariffs have become a weapon in our ongoing trade wars with China, the European Union, and even Canada. But what may appear to be a simple mathematical approach—raising the price on a foreign product to spur sales of a domestic alternative, for example—is anything but, says Xiang Ding, a GSAS PhD candidate in the business economics program at Harvard Business School. Indeed, the import tariffs now being imposed—or threatened—by the United States and its trading partners will likely have a wide array of unexpected outcomes.

Tariffs, an import or export tax imposed between sovereign states, were first imposed by the United States in 1789, in the inaugural legislation of the then new country’s first Congress. These taxes—or customs duties, as they are also know—may have helped raise money for a fledgling democracy and protected its new industries. Globally, tariffs were applied primarily to commodities, such as cotton and sugar, by countries with fewer trading partners and simpler trading relationships.

Ding, who grew up in Germany, Finland, Singapore, and Hong Kong before attending Princeton as an undergraduate, says that in the modern era, tariff application doesn’t take into account the realities of the contemporary global marketplace. “Even 50 years ago, production was incredibly simplistic,” says Ding. “Today, global trading patterns are much more intertwined, and production processes are more technologically intensive.” The consumer items now being bought and sold—those soybeans or iPhones—are no longer the focal point of most businesses. Instead, it’s the ideas— the technology—behind the products that have the most value.

Today, global trading patterns are much more intertwined, and production processes are more technologically intensive.—Xiang Ding

“When we think about the 21st century, so much of the value added comes from the brains of the R&D workers, scientists, and managers,” says Ding. As a result, contemporary companies look at a larger picture by increasing spending on activities categorized as “intangibles,” such as research and software. Since 2000, the spending on intangibles by US manufacturing firms has outpaced spending on traditional forms of capital expenditures, such as production plants or machines. “In this new era, firm-wide resources that generate knowledge are supremely valuable,” he says. “Trade plays an important role in this regard. A firm’s export opportunities and the degree of competition generated by imports shape the firm’s incentives to acquire new knowledge and develop new technologies.”

Over the same period of time, manufacturing has become more globally interconnected, with industrial production increasingly relying on a supply chain consisting of inputs, or parts, made in one country being assembled into a final product in another. “Production is incredibly linked,” says Ding. “Tariffs may reduce competition in the industry they target, but they also raise the cost of parts produced elsewhere.”

Beyond Borders

If this relatively new focus on intangible resources within firms and the increasing global complexity of manufacturing has impacted how effective a tariff can be, Ding’s particular area of research—companies that span multiple industries—adds an additional complication. Multi-industry firms make up only 20 percent of US companies, but they are responsible for 75 percent of domestic manufacturing’s gross output.

“It’s fascinating that most of what we consume comes from a handful of multi-industry firms, like Amazon, Google, and Procter & Gamble,” he says. “Take General Electric, for example, which operates in seemingly random industry segments, like aviation turbines and X-ray scanners.” Many are familiar with the concept of economies of scale—that it is cheaper to produce more of any one thing—but Ding is looking at economies of scope, how the different divisions of these broad-ranging companies work together.

“The question I’m interested in is whether there’s anything that weaves together the activities taking place within the different areas of these firms,” he says. “Whether they have resources that allow them to reap cost efficiencies from their scope of operation.”

As he sought to answer that question, Ding evaluated US Economic Census microdata to investigate economies of scope. What he discovered and published in his most recent paper, “Intangible Economies of Scope: Micro Evidence and Macro Implications,” is that the answers will have real-world ramifications.

“A key finding in my research is that intangible inputs generate cross-industry cost efficiencies, or economies of scope,” he explains. “Regular, physical inputs do not.” Steel bars, for example, can only be used in the product they were designed for. If a firm improves its IT infrastructure, all its products benefit. This cross-divisional benefit within a company—coupled with the global nature of the production chain and the outsized influence of multi-industry companies—contributes to a global economy that has become an increasingly intricate engine in the 21st century, reliant on many interdependent parts. Hitting any one of those parts with a blunt, outdated tool like a tariff is likely to have unforeseen consequences.

For example, an import tariff can reduce competition and help domestic companies gain market share, allowing for an investment in research and development. If technology developed for one product in a multi-industry company is found to be useful in another, unrelated area, the company may decide to roll it out more broadly. However, the same tariff could increase the cost of materials imported by the company, which would instead curtail investment in research and development. Instead of benefiting US companies, Ding believes that tariffs could have the opposite effect, a function of the complicated nature of contemporary trade.

“On the one hand, a tariff is making it more profitable to invest in research and development, because competition is lower,” he says. “At the same time, it may increase the cost of production.” Tariffs, originally designed to benefit wholly domestic enterprises focused on a single industry, now have contradictory effects on these large multi-industry, multinational firms: Any benefit arising from an intangible investment rolled out across the company could be overshadowed by an increase in manufacturing costs in one area of the company. The choice? Discontinue investment in intangibles or pass the increased cost onto the consumer.

Paying a Price

Despite the fact that tariffs are often suggested as a primary way to regulate trade, alternatives do exist: Government subsidies offer a more targeted benefit to specific domestic industries. “It would be more precise to subsidize, for example, steelmakers directly,” says Ding. “Some countries, like China, can do that, because they have the political will and provide trade protection for certain industries.”

Often, the rationale for tariffs is less about protecting domestic industries as to be punitive—to punish trading partners that will not agree to favorable terms. “What I fear is that sometimes the motivation behind the use of tariffs is not necessarily to promote a particular industry,” says Ding. “It has much more to do with underlying political motivations—both in terms of engaging in a dialogue with a particular constituency at home and as a bargaining tool when it comes to the conduct of US policy abroad.”

Politically motivated or not, tariffs often lead to companies and ultimately consumers paying a price, despite the investment in intangibles, such as research and development. “US companies might end up being more profitable, and they might develop new ideas,” Ding says. “But it would be incredibly hard to generate research proving that tariffs were positive overall for the US consumer.”

“Ding’s work on such large multi-industry companies has revealed how a positive demand shock in some industries boosts productivity in other parts of the economies,” notes his advisor, Marc Melitz, the David A. Wells Professor of Political Economy. “And conversely, tariffs that hit just a few key sectors can have significant negative consequences that spill over to many other parts of the economy.”

For the global economy, the overall effect is likely to be uncertainty, a dangerous prospect, according to Ding. “With tariffs rapidly proposed and withdrawn, it becomes incredibly hard to gauge what future conditions might be,” he says. “This political and economic uncertainty could have a chilling effect on corporate investment in intangibles.” Smothering, in other words, the activities on which our modern economy is based.

Even as the current trade war threatens, Ding retains hope. “I’m optimistic that policymakers at the end of the day are sensible and rational creatures,” he says. “I’m also optimistic about the ingenuity of businesses to find alternatives.” As he points out, in economics, balance usually asserts itself. Developing countries could be poised to benefit as trade barriers go up between the US and China.

“If the US imports less from China due to tariffs,” he says, “that might promote growth in the neighboring Southeast Asian countries that so desperately need it.”

Photo by Jared Leeds, Illustration by Aleksandar Savić

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast