A History of Queer Survival

How Sappho’s legacy has stayed alive over thousands of years

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

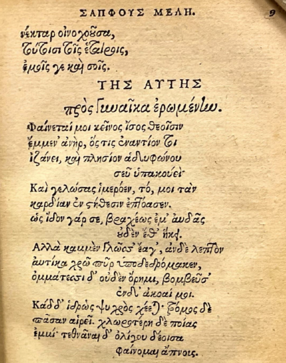

. . . when I look at you even for a short time,

it is no longer possible for me to speak

but it is as if my tongue is broken

and immediately a subtle fire has run over my skin,

I cannot see anything with my eyes,

and my ears are buzzing

The lines of this love poem by the ancient Greek poet Sappho of Lesbos (ca. 620–570 BCE) convey powerful feelings, appealing to multiple senses to describe overwhelming romantic desire. Remarkably, these words and emotions have survived thousands of years and continue to touch readers today.

“Sappho has an exceptionally long afterlife,” says Katherine Horgan, a PhD student in English at Harvard’s Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “It’s fascinating to see how readers react to her over huge spans of time.”

Horgan’s 2025 Harvard Horizons project, “Living Sappho: Imitation, Imagination, and Revivification in Early Modern England,” examines the many texts that have carried Sappho’s legacy as both poet and queer woman over the centuries. Horgan’s work challenges existing scholarly trends that have separated Sappho’s poetry from her personal biography and thus have downplayed the impact of the poet’s queer identity in the early modern period. By reuniting Sappho’s poetry with her biography, Horgan looks beyond typical historical sources to present a new understanding of Sappho’s position in queer history––and of the ways authors and readers connect across time.

Shedding New Light on a Shadowy History

“Sappho is often portrayed as a mysterious figure,” Horgan says. This is, in some ways, for good reason. Sappho’s surviving poetry consists only of fragments preserved in ancient manuscripts. At best, scholars can only make informed guesses as to what words might have filled the holes in a decaying papyrus or what larger context might have surrounded a surviving excerpt.

Likewise, knowledge of Sappho’s life story is uncertain. “There are so many contradictory accounts of who her parents might have been, whether or not she had a daughter, the names of her students, friends, and lovers. However, the names of her loves remain remarkably consistent across accounts over centuries, and some are even mentioned in Sappho’s poems,” Horgan says.

Although we have lost many of Sappho’s writings and biographical details over the ages, Horgan suggests the poet’s fame has endured due to a combination of her sublime poetry, queer sexuality, and androgynous gender identity. This combination made Sappho a subversive and attractive figure for curious readers and scholars in many different historical periods. While mainstream scholarship has largely thought Sappho’s queerness was suppressed in the Renaissance, only becoming significant to readers starting in the 19th century, Horgan’s examination of a broader range of sources suggests that Sappho’s queer history mattered long before. “With her combination of philological rigor and fearless critical vision, Katherine’s dissertation is helping to rewrite both the history of literature and the history of sexuality in early modern Europe,” says Harvard Professor of English Leah Whittington, who is the chair of Horgan’s dissertation advisory committee.

One way Horgan hopes to retell Sappho’s story is to challenge ideas of her as a shadowy, unknowable figure. “As is true of all distant historical figures, the facts we know of Sappho’s life are very few. But I think we can know for certain that whatever she was,” Horgan insists, “she was fantastic! In the brief 45 or so years she was alive, she must have made quite an impression to inspire 2,600 years of conversation.”

After her death, Sappho seems to have gained celebrity status because of both her fascinating poetry and her personal life. “Readers have always loved her poems,” Horgan says, “and it also seems that Sappho’s androgynous gender just blew people’s minds.” Horgan explains that, in addition to her romantic interest in women, Sappho departed from feminine norms of her time. “Her femininity was linked with masculine ideas of the poet, intellectual, and lover,” Horgan says, “and that affected the understanding of her gender within the context of a highly gendered world, one which was also a differently gendered world than ours today.”

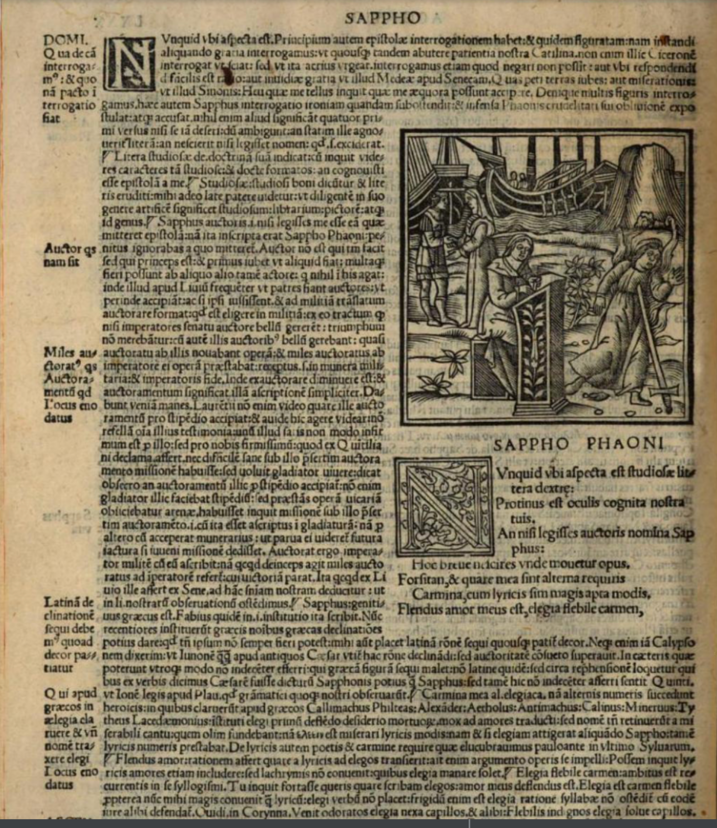

Beyond Sappho’s lifetime, the ways her reputation and poetry have endured over the years provide valuable information not just about Sappho herself, but also about the perspectives of the later authors who have written about her and the cultures they represent. For a period of several hundred years, lasting between the 7th century and the early Renaissance, Sappho’s poetry was lost. Until some of her writing resurfaced in printed books of the 1550s, stories about Sappho’s life were the primary way her legacy survived. Even during the time when no one could read Sappho’s poetry, readers were still reading about Sappho herself, though these texts are sometimes found in unexpected places.

One example Horgan has uncovered came hidden within scholarly commentaries on works of ancient Roman literature. Substantial information about Sappho, she explains, was transmitted within an analytical text, included in a pedagogical book, about a poem by Ovid that had paid tribute to Sappho by way of a fictional letter written from her perspective. “In the period when Sappho’s poems were lost, there were texts written by other authors that explored her poetic and biographical legacy at length,” Horgan explains. “These texts were often included in schoolbooks called ‘commentaries’—detailed analyses of ancient writings directed at students of Latin. When scholars published writings about Sappho, they wrote explanations of Sappho’s history and biography, and in them are embedded detailed descriptions of Sappho’s queer gender and sexuality.”

By looking at texts like this one, Horgan aims to expand our understanding of how Sappho was received in the early modern world and to extend the knowledge of Sappho’s queerness farther back in time. “With her detective work into the way early modern critics buried their knowledge of Sappho in editions of Ovid, Katherine Horgan has overturned conventional ideas about Sappho as a ‘lost’ poet,” says Harvard Assistant Professor of English Anna Wilson, who is also one of Horgan’s dissertation advisors. “Her research promises to restore Sappho to prominence as a poet whose influence spread across the medieval and early modern period, long before she was previously thought to have been ‘rediscovered’––and to ask why we were so invested in her being lost in the first place.”

As Horgan tells it, “Scholars often look for Sappho in the wrong places: if you search for the queer Sappho in texts approved by the church, or directed at polite young ladies, you’re not going to find her––or anything very unconventional for that matter. You’re going to find authors writing acceptable things to protect their own reputations. Texts written for students and scholars, on the other hand, include some of the most explicit descriptions of Sappho’s sexuality. The authors of these texts were often more concerned with writing accurate things about Sappho’s poetry and biography than they were with pleasing the church or a patron. As scholars and students writing for other scholars and students, these texts’ authors prioritized preserving Sappho’s complete history in all its queerness.”

Writing as a Space for Play

Horgan’s study of a variety of sources shows that Sappho’s historical reception was not as marginalized as typical scholarly narratives often assume. In addition to Horgan’s interest in the subversive appeal of Sappho’s queer identity, Horgan has observed a spirit of play surrounding the poet throughout history, which she thinks is linked to Sappho’s tender poetic portrayals of love. “The queer desire Sappho expresses in her poems is gentle even as it is overwhelming. Her gaze isn’t predatory, possessive, or aggressive, which I think makes readers feel like her poetry provides a safe space to explore their own genders and sexuality,” Horgan explains. “The authors I study have an enormous amount of fun experimenting with the erotic voice Sappho develops in her poetry.”

The ability to have fun with Sappho’s legacy has led not only to literary impersonations of Sappho’s poetic voice, but also to inspiration for new stories. Horgan cites a notable example in 16th-century English poet Philip Sidney’s Old Arcadia. Horgan reads Sidney’s romance as a work in which the author imagines how a gender-bending character, modeled on Sappho, might fit into society. The story’s male main character, hoping to get closer to the woman he loves, disguises himself as a woman. In the process, his Sapphic disguise causes chaos and confusion throughout his social sphere: his female persona is so attractive that both men and women––his own friends, his beloved’s parents, and the beloved herself—fall madly in love with him/her. As the story explores what Sappho’s gender might have looked like, it also contains the first translation of one of Sappho’s fragments into English, quoted within the text.

“Authors like Sidney had a lot of fun with Sappho,” Horgan says, “as did millennia of readers before him. The very fluidity of Sappho’s gender seems to have lowered the stakes for gender and sexual exploration: men pretending to be Sappho need only be a little more feminine, and women pretending to be Sappho need only be a little more masculine.” Horgan suggests that Sappho’s biography thus became a safe place to experiment: “At the end of Sidney’s book, the hero takes off the disguise, the boy marries the girl, and everything settles back down,” Horgan explains. “Stories like Sidney’s are a place to try something new while risking fairly little. But even if these stories resolve their queer questions in heterosexual unions, the very fact of the exploration makes queerness possible in the minds of readers.”

The Experience of Being Alive

In addition to her historical and cultural importance, Sappho also holds personal significance for Horgan. “My interest in Sappho intersects with my own identity as a queer person,” Horgan explains, “and I think many queer people think of her as an ancient ancestor.” Likewise, Horgan says that this research has changed her own ideas about queer survival and history. “As a young queer person,” Horgan reflects, “I really felt that my queer history was one of destruction, violence, and secrecy, and that Sappho was the exception that proved the rule: even the queer poetry of the most celebrated poet of all time only survives in fragments.”

“While queer history contains so much pain,” Horgan says, “my research revealed to me Sappho’s powerful narrative of queer survival—a vibrant, brilliant, and compelling figure whose sexuality was impossible to ignore. In fact, people’s fascination with her gender and sexuality—whether they try to suppress it or celebrate it—has made her queer legacy indestructible.”

Horgan also sees her study of Sappho’s legacy as an invitation to rethink how we understand relationships between authors, texts, and readers. “As a young reader, I became interested in authors’ connections with one another. Authors are first and foremost readers, and they had relationships with writers and readers of their own time, with writers before them, and also with me,” she recalls. “Reading is fundamentally the experience of contacting someone else, even someone long dead. To write a book is a profound act of faith: it’s launching a text into the future and hoping against hope that someone—you don’t know who––will read it and understand.”

Likewise, Horgan feels her research highlights the ways that engaging with the work of any author––including Sappho’s writing––can be a powerful way for readers to experiment with new ways of living and thinking. “An author can reach out through a book, take your hand, and say, ‘This was my experience of being alive,’” Horgan reflects, “and then you, as a reader, are free to say, ‘Oh, that’s not my experience,’ or, ‘Oh, thank you. I needed to hear that,’ or to observe how things in the past were very different. My work is mostly about trying to recover the delight of meeting someone new, living or dead, through a book.”

In fact, it is these experiences of difference made possible by reading, Horgan proposes, that can transform our ideas of the present and future. “Working to recover the difference of the past through reading,” she says, “is a way of imagining a different future. So often readers try to find the ways that the past was like the present. But if the past and the present are the same, what hope can we have for a better future? By trying to recover the radical difference of the past—just as the poets I study tried to recover Sappho—it becomes possible to imagine new ways of being in the future.”

As people today seek novel responses to problems old and new, Horgan argues that literature and history are our most valuable tools in that process. “We all want to imagine something new—we need to imagine something new,” Horgan says, “and the poets I study all do that by reimagining someone very old. Sappho has challenged readers to rethink their world for thousands of years,” Horgan says. “If it’s good enough for them, it’s good enough for me.”

Don't miss this year's Harvard Horizons Symposium in Sanders Theatre on Tuesday, April 8, 2025. Free and open to the public.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast