Helping Global Youth to Thrive

Innovative model has big impact on mental health, at scale, for communities that need it most

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

As a helpline volunteer for the National Alliance on Mental Illness in 2016 during a hiatus from her undergraduate studies at Harvard, Katherine Venturo-Conerly heard from people who were suffering and in need of support. The callers were struggling with high levels of anxiety, depression, or other symptoms. Many had trouble getting medication and therapy. Some did not have stable housing. It was Venturo-Conerly’s job to refer them to organizations where they could get the care they needed. Too often, though, those resources were nearly impossible to access.

“Many of the supports no longer existed or had a completely full waitlist,” she says. “Clients would call, and the line was dead. The remaining organizations had such long waitlists that they could not be available for people in crisis. I was shocked by how much need there was and how the system of care was overburdened trying to keep up. So, I decided to do something about it.”

Now a PhD student in clinical psychology at Harvard's Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 2025 Harvard Horizons Scholar Venturo-Conerly is on a mission to revolutionize access to effective mental health care—particularly for young people. Her research project, "Tackling the Global Youth Mental Health Challenge: Lessons from Psychotherapy Research in Kenya," focuses on creating and implementing effective, accessible mental health interventions for children and adolescents in multiple countries, with a particular focus on Kenya. As co-founder of Kenya’s Shamiri Institute with her Harvard College classmate Tom Osborn, Venturo-Conerly is developing a collaborative and sustainable approach to bridge the mental health care gap around the world.

A Passion for Mental Health, A Commitment to Equity

Mental health is a global challenge, particularly in poorer countries, according to John Weisz, Harvard’s Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences and Venturo-Conerly’s faculty advisor. “In Kenya and many other low- and middle-income countries, a major need for youth mental health care is combined with a severe shortage of professional providers and scant funding for services,” he says.

It was that shortage Venturo-Conerly had in mind when she decided to pursue a career in clinical psychology and global health equity. “I want people around the world to be able to access the mental health care that they need,” she says. “And I want that care to be effective within their personal context.”

In Kenya and many other low- and middle-income countries, a major need for youth mental health care is combined with a severe shortage of professional providers and scant funding for services.

—Professor John Weisz

She and Osborn also wanted mental health care to be sustainable. That meant developing resources within low- and middle-income countries, rather than importing them. “When I was learning about global mental health, I noticed that not all work in the field involved ownership by in-country experts, which makes it really tough to be culturally appropriate and sustainable,” she says. “To make a long-term difference, we need systems that help prioritize and support local capacity for research and caregiving and that direct funding to these efforts.”

With these goals in mind, Venturo-Conerly and Osborn in 2019 launched Kenya-based Shamiri—the Kiswahili word for “thrive.” The institute’s model works around the lack of professional providers in the country by employing laypeople—high school graduates interviewed and hired based on their natural counseling abilities, empathy for others, and knowledge of the problems often faced by students. Weisz calls this approach “a valuable innovation.” “It’s efficient and effective to train lay providers to deliver evidence-informed care and help address youth mental needs in a region where there are few professional providers.”

A Positive Approach

Osborn notes that Kenya, like countries around the world, is facing a surge in mental health concerns among youth. “Rates of depression and anxiety are particularly prevalent in young people, with one in two reporting symptoms,” he says. “In Kenya, there are 10 million people aged 15 to 24. The prevalence of depression and anxiety and the lack of access to affordable care provided an opportunity for impact at scale if we could provide culturally relevant innovative care.”

In Shamiri’s three-tiered model, lay counselors form the base, receiving around ten hours of training before delivering mental health care to Kenyan high school students. Staff with master’s or bachelor’s degrees form the second tier, training the lay providers as well as providing supervision during the intervention. Finally, there’s a top tier of experts with a PhD in psychology or an MD in psychiatry who are available in case counselors need to escalate care for those with very high symptoms or where those symptoms present some risk to the participant or others.

The intervention itself is designed for Kenyan high schools, where Western concepts of mental illness can be stigmatized. Shamiri’s model emphasizes evidence-based positive concepts that make the program more acceptable and appropriate for the schools in which it is introduced. One is the notion of a “growth mindset,” which sees challenges as opportunities to learn, develop, and thrive. Another is a focus on gratitude—both in terms of internal appreciation and external expression. The Shamiri intervention also asks students to consider their personal values, how they apply them, and how to incorporate them into future goals.

Weisz says this positive approach is another important innovation. “Instead of focusing on ‘mental illness’ or ‘psychopathology,’ Shamiri focuses on conveying key principles of effective living—feeling and expressing gratitude, identifying and acting on one’s core values, and trusting that one’s goals can be reached through effort.” Venturo-Conerly adds that “a lot of Western mental illness diagnoses and institutions are tied to colonization and control in Kenya.” The institute’s model was designed to avoid recapitulating that history.

Shamiri chose public high schools as their delivery site for ease of access to a large youth population. It chose young people as the target demographic to maximize the impact of the intervention. “In the field, it’s thought to be easier to help young people change—and for that change to stick—than adults,” she says. “I think there's at least some truth to the fact that children and adolescents are growing and changing more than grown-ups are. The principles we teach are simple, intuitive, universal, and easy to convey quickly—including to young people, with whom they’ve also been tested before.”

Dr. Christine Wasanga, senior lecturer in psychology at Kenyatta University in Nairobi, Kenya, and one of the clinical experts involved with Shamiri, says that the program is effective because it works around the challenges of providing care.

"The stigma around mental illness often prevents people from seeking help," she says. "There are more in need of care than there are providers, and the cost of seeing a psychiatrist or psychologist can be prohibitive. The Shamiri model circumvents stigma by presenting content as character strengths, so more young people participate. The intervention is presented by peers with whom students can easily identify and relate. Because it's group-administered, proactive, and preventive, it's also less costly, both in the short and long run."

Venturo-Conerly is quick to point out that the intervention isn’t focused exclusively on treating mental illness. In fact, many of the program’s participants don’t struggle with anxiety, depression, or other symptoms. The institute wants to improve well-being, grades, and life outcomes for all students. “Some people will have mental illness, and some people won't,” Venturo-Conerly says. “For the sake of scale, we are delivering often in universal settings within schools, and sometimes we select people based on personal characteristics—based on who we think will benefit most. But typically, we're delivering universally so that everyone within the school can receive it.”

Impact, at Scale

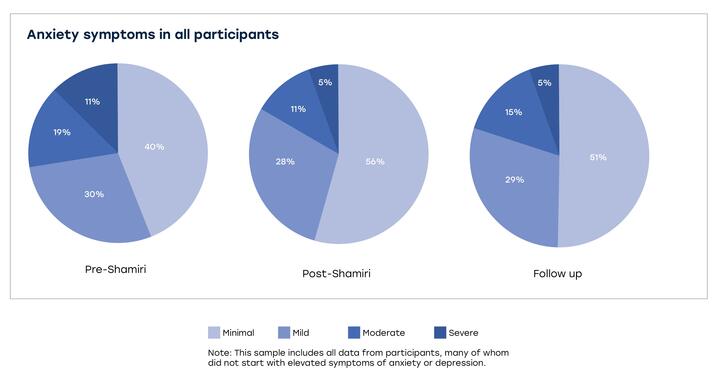

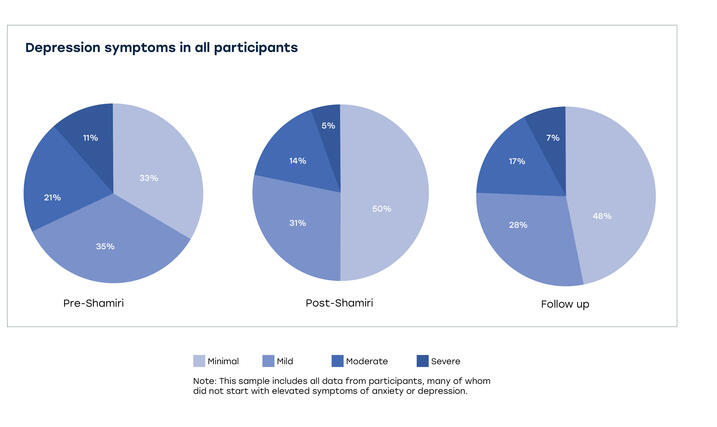

Venturo-Conerly, Osborn, and their collaborators gauge the program’s impact through surveys that allow students to self-report their symptoms, questionnaires focused on well-being and character strengths like growth mindset and feelings of gratitude related to the intervention, and gauging academic performance. By these measures, Shamiri’s work has had a significant effect. The institute’s 2022 annual report showed a 31 percent and nearly 42 percent reduction in symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively, among participants. In all, over 80 percent of students report experiencing minimal to no symptoms of anxiety and depression after taking part in the program. Moreover, there is preliminary evidence of a positive impact on schoolwork. “In our first trial, we found grades improved significantly more in the Shamiri intervention group than in a study skills active control group,” Venturo-Conerly says. “We're pretty excited about that.”

Inexpensive, relatively easy to deliver, and with a positive orientation that appeals to participants, Shamiri’s intervention is being applied at scale. Since its founding, the organization has trained more than 2,500 providers who have completed over 38,000 group therapy sessions and served more than 137,000 youths in over 300 schools. And Osborn says that Shamiri is just getting started. “In Kenya, we served 100,000 youths in 2023. We’re working toward reaching one million per year by 2027.”

Up next for Shamiri? More testing to determine the best way to expand the program, develop the intervention, and tailor care to the needs of different students. “We're testing multiple dissemination strategies, including engaging with partner organizations to deliver care,” Venturo-Conerly says. “We’ve also tested a life skills intervention that is in preliminary analysis and seems to be effective for mental illness symptoms and improving well-being. Now we want to know which intervention to assign each youth to maximize their benefit.”

In our first trial, we found grades improved significantly, more in the Shamiri intervention group than in a study skills active control group. We're pretty excited about that.

—Katherine Venturo-Conerly

The long-term goal for Shamiri is to move beyond Kenya to improve the effectiveness of mental health interventions for young people around the world. “We are expanding our footprint on the continent,” Osborn says. “We currently have pilot projects in Ethiopia and South Africa.”

The duo hopes to bring similar approaches to the United States as well, where Venturo-Conerly also researches youth psychotherapies in community and school settings. The Horizons Scholar says she is devoted to rigorous research, always partnering with and keeping in mind the needs of the communities it may serve.

“My interest is in global health equity,” she says. “People with mental illness, just like people without, can have full, meaningful lives, especially with appropriate support. Ultimately, I want people everywhere to be able to enjoy life and be fully immersed in their experience of it. So, my goal going forward is to do community-based research to improve mental health care for young people, not only in areas with many professional resources but also in the many parts of the world in which accessing professional mental health care is quite difficult, such as in many parts of lower- and middle-income countries. That’s where 90 percent of youth live, so that’s where it’s needed the most.”

This research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Research Service Award

Katherine Venturo-Conerly's work on statistical learning and youth psychotherapies was funded by the National Institutes of Mental Health.

Don't miss this year's Harvard Horizons Symposium in Sanders Theatre on Tuesday, April 8, 2025. Free and open to the public.

Banner photo by Shamiri Inc.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast