Harvard’s First Black PhD: Part 2—W.E.B. Du Bois, From Social Scientist to Global Leader

In the decades after becoming the first Black US citizen to receive his PhD from Harvard, W.E.B. Du Bois helped transform sociology from theory and speculation to a social science rooted in rigorous methodology and hard data. But despite conducting groundbreaking research, particularly on the lives of Black people, Du Bois chose to leave the academy and become an activist, co-founding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. What inspired him to make the change? And what can we learn today from Du Bois’s research, his writing, and leadership? The Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer David Levering Lewis joins us for part two of our look at the life of the early 20th century’s leading intellectual and spokesperson for Black liberation.

(A word of caution: Several minutes into the show, Professor Levering Lewis describes an episode of racist violence. We have preserved that portion of the conversation, rather than editing it out, because it describes a turning point in Du Bois’s life and career.)

This transcript has been edited for clarity and correctness.

Du Bois completed his PhD at Harvard, and then he went on to an academic career, first at Wilberforce University and then at the University of Pennsylvania. You portray his research at Penn on the Black community in Philadelphia's Seventh Ward as a landmark in sociology. What made this study so remarkable?

Sociology was armchair stuff, really. It was theory unobserved. It wasn't empirical. No, he learned from his professors that you must have the numbers. And so he did something that is very American, really, but he's the first to do it, and that is simply to put his shoes on and knock on every door in the Seventh Ward.

Now, mind you, can you imagine a man with a Wilhelmine mustache knocking on your door as an ordinary worker, a minority worker, and being asked questions? But he had remarkable success. The tabulation of this evidence was really extraordinary. And it should have been the breakthrough that will come only much later. There is a very fine two-volume study of Polish people in America—the name of that author escapes me now—but it benefited from the kind of empirical precision and thoroughness that Du Bois had established.

But he didn't just have all this documented data. He said there is a class that has succeeded with all the resistance upon it, and then you have the lower class that has not. And this has something to do with opportunity, which had escaped just about everybody. You mean African Americans work hard and do things, and really are going ahead? But a great majority do not. And there's a link between their salaries and their opportunities. It is so evident now, but that was most helpful. And he also had the benefit of the names of women who were in a new movement to make available opportunities for the immigrants coming into this country. And they worked with Du Bois. And so The Philadelphia Negro is just quite extraordinary. And finally, it has been accepted by the American Sociological Association as a fundamental work of sociology. And so it straddles two fields of history and sociology.

Du Bois conducted other studies for the Bureau of Labor Statistics and then at Atlanta University. Taken as a whole, how should we understand his contributions to social science?

Well, it could have been far greater. And I think now it is, because The Philadelphia Negro was almost a one-off. And then Du Bois goes to Atlanta University, which is an extraordinary institution. And there, having written something in The Atlantic Monthly that introduced Du Bois to the world, really—the title of it was so descriptive of what it was about, but it had everything in it about divided selves and about the difficulties of being welcomed in America. I cannot remember the title of that Atlantic thing, but what its consequence was that the president of Atlanta University welcomed him and said immediately, “We will place at your service funds that you can commence to do something,” the Atlanta University studies.

And so there was a 10-year timeframe from 1897 until he leaves for the NAACP. The African American family, the African American class structure, the African American economics—the entire panoply of African American activities empirically looked at by students. My own mother, for example, remembered that as she was a very young person, he had doled out something for her to do and said, “Go and bring me back some statistics on this.” So the Atlanta University studies were really revolutionary, but they were ignored—totally ignored.

And when Du Bois went to meetings of the Sociological Society and other distinguished organizations, they would say, “Oh, this is fine what you're doing.” But there was no connection, no link. And we will have money—money for, you know. But of course, that was because even Atlanta University realized that what Du Bois was finding was so destabilizing to the "separate but equal" agreement that had been accomplished by 1896 with a Supreme Court decision that would change the world for everybody: Plessy v. Ferguson.

But even given the neglect he experienced from funders and his peers, why did Du Bois leave academia when he was clearly doing such important work?

So then we're going to get another moment when a man, Sam Hose, has been lynched brutally. Du Bois is going to go to the Atlanta Constitution with a document to be printed, to give to the publisher of the Atlanta Constitution. And as he walks down the street from Atlanta University, he sees in a grocery store the knuckles of the remains of this butchered man. Du Bois is stunned. He turns around, he puts that document in his jacket pocket, and he walks back to Atlanta University.

And he says he had thought that social science would change the world, but he can see now that the world is not interested in the facts that he can get. And so there must be action; the classroom will have to be surrendered to an organized resistance.

But then, of course, he did something which reinforced his depression. In Lowndes County, he had done something quite extraordinary. The Bureau of Labor Statistics was curious. He found that nobody owned anything in Lowndes County, and there's a good reason for it. He wanted to know that. And he soon realized that to talk to some of the white landholders would probably not be so revealing. And so he got extra money to hire white men who would join in this enterprise. And they, too, turned over the evidence—the verbal evidence.

And so he had this compelling document which showed racism raw and its economic and landholding consequences inevitable. He sends it in, and nothing happens. Then he writes, and they say, “Professor Du Bois, there's something there, but it's not quite right. And you need to go back and you get your figures straight.” He does that, and he does it again. And then he realizes. So he says, “But what's going on?” And they say, “Well, we're not going to use this.” And he said, “Well, I want it back.” Well, they said, “No, it's gone.”

And so the document vanishes. And that . . . told Du Bois that if knowledge is to be useful, it must come with a fist. It must come with an organization funded sufficiently to make a necessary difference in the structure of the society. And so it's time for us to move on.

Having tried with the Niagara Movement to organize African Americans who were most offended by the way history was going for them, it wasn't until the abolitionist children realized that the racial problem has become a national blot that it got the attention of those people. Oswald Garrison Villard—a name that spoke volumes. He was a Villard, he was a Garrison. And he will convene the first meeting of what becomes the National Association, and Du Bois will give it its title. He says, “No, no, no, it can't be the ‘National.’ It must be the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).” Already, he was thinking of the kind of global consequences of what he was embedding himself in.

In 1909, Du Bois became a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and its flagship publication, The Crisis. Talk about the impact that the organization and the publication had on the struggle for Black liberation and civil rights.

A parent would say, “Until I have finished reading the Bible, we will then read The Crisis, and then we will have lunch.” Oswald Garrison Villard said, “You know, we have enough magazines. They're like flies; they don't do much.” And Du Bois said, “You'll be surprised.” And so they were. Its circulation would grow until, by 1919, it had 100,000 subscribers, which matched The New Republic, for example.

But for African Americans, it was canonical. And the kind of articles were, again, like The Philadelphia Negro. Du Bois got in his Plymouth, and he was going to places where there were problems to observe and take notes and come back. And so it had a kind of virility and first-sightedness that was remarkable. And it was uncompromising—utterly uncompromising.

Then the Niagara Movement brought with it the whole business of equality—social equality as well as political equality. It even had a kind of feminist enlightenment. Du Bois was writing—he wrote “The Damnation of Women”—in which he said that the rights of women to the control of their own bodies is part of their identity, which was a quite forthcoming idea and in sync with Margaret Sanger, who would soon be a close collaborator.

Yeah, it was quite powerful. And one should credit Jessie Fauset, the very good literary editor of The Crisis, for being the person who identified the whole talent that will populate the forthcoming Harlem Renaissance. Their contribution there was quite considerable. Then we have to acknowledge that we get several Du Bois issues, and that each decade, probably, we're going to have a different one. As the decades go by and as he moves left, he leaves behind a lot of quizzical people who said, “Well, I thought we understood it, but he's really going very far left. And is that wise? Should African Americans identify themselves as unreliable, as unpatriotic?”

Well, perhaps not. Great puzzlement came when, in 1934, as Du Bois leaves the NAACP, he announces that segregation is the solution, not integration. And this is head-scratching to everybody. We thought that this organization fearlessly went for cooperation to mainstream. “No,” said Du Bois, “haven't you noticed there's a depression? Everything has collapsed. If we support our own institutions and make them cooperative, we'll be surprised by how we will be able to endure this downturn.”

Because, without criticizing, as a major argument, the insufficiencies at the end of the New Deal—since Eleanor Roosevelt was shown an indispensable ally—nonetheless, the New Deal was not interested in African Americans, but the white impoverished. But that didn't work out. And so Du Bois leads the NAACP and returns to the new Atlanta University. Rockefeller financed it handsomely. And there, as a professor of sociology, he gathers around himself the best and the brightest, as it were—a cliché useful in this moment—with Rayford Logan and with the sociologist from Haverford and a number of other New England-trained PhDs.

Finally, we talk about the final decades of Du Bois’s life, beginning with his experience with the American Historical Association (AHA) and the House Un-American Activities Committee, known as HUAC. How were Du Bois’s views shaped by the politics of class as well as race, and what can we learn from them today?

In 1943, Du Bois attended for the first time an AHA meeting since the one way back in 1899. And so people were prepared to welcome Du Bois back into the mainstream. But unfortunately, HUAC had come along, and it had resulted in the NAACP having to purge itself of suspect members as a result of a curious piece written by Arthur Schlesinger. Indeed, and there's this great panic.

And Du Bois also had gone before the people who were created by the Talented Tenth concept. And there he had said in 1948, “I abjure the idea of the Talented Tenth because it has become elitist, and history moves with the input of the people.” And we must add that kind of organization. And it is Karl Marx who tells us what we must do. And it was a great shock to the Talented Tenth hearing this.

And they thought—and this is just the moment when Fifth Amendment declarations are becoming mandatory, when Americans right and left are going before a committee—Du Bois then became toxic. And it will be a period of time in which he's unwelcome except on the left. And that suits him fine. But it'll be a long time before he comes back once he's indicted as a foreign agent by the Truman administration. And though he expected to have Einstein come from Princeton to be a character witness, the judge decides that this whole indictment was a mistake and annuls the trial.

And Du Bois has no passport, however, until it's restored and he can go back to Germany—a new kind of Germany. And we're seeing that honorary degree in economics that he didn't get many years earlier given by a German Democratic Republic decision. He goes on to Czechoslovakia and on to China. Now, his birthday will be a national holiday decreed by Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai.

And then, of course, finally, he leaves and goes to Accra, Ghana, to finish the Encyclopedia Africana, as it is called. Du Bois has a kind of mixed achievement that perplexes many people, and yet is so valuable at a time when the understanding that capitalism, as he said, can never benefit the great mass of people. It's not supposed to. And I think we see that if you don't know the history, this bloody history that we've all gone through down through the centuries, then we will, of course, repeat it.

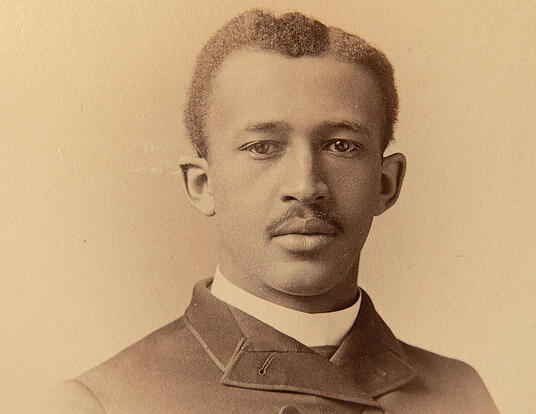

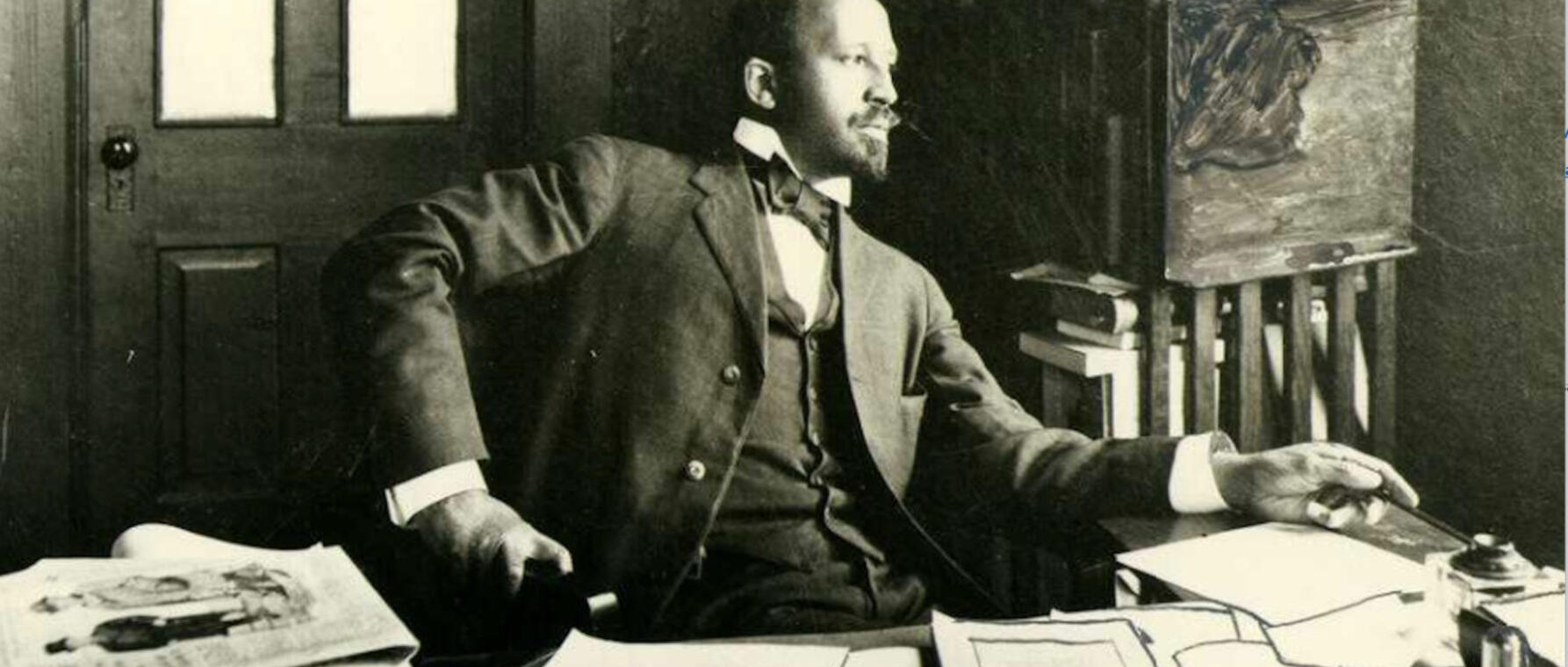

Thumbnail photo courtesy of UCCS Kraemer Family Library / Banner image courtesy of UMass Archives.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast