Harvard’s First Black PhD: Part 1—W.E.B. Du Bois the Student

By 1897, the hopes of Reconstruction after the US Civil War had been dashed by Jim Crow and white supremacist terror. But the young Black social scientist, writer, and intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois pushed back, asserting that Black folk were central to the American project. “We are the first fruits of this new nation,” he wrote in 1897, “the harbinger of that black tomorrow, which is yet destined to soften the whiteness of the Teutonic today.”

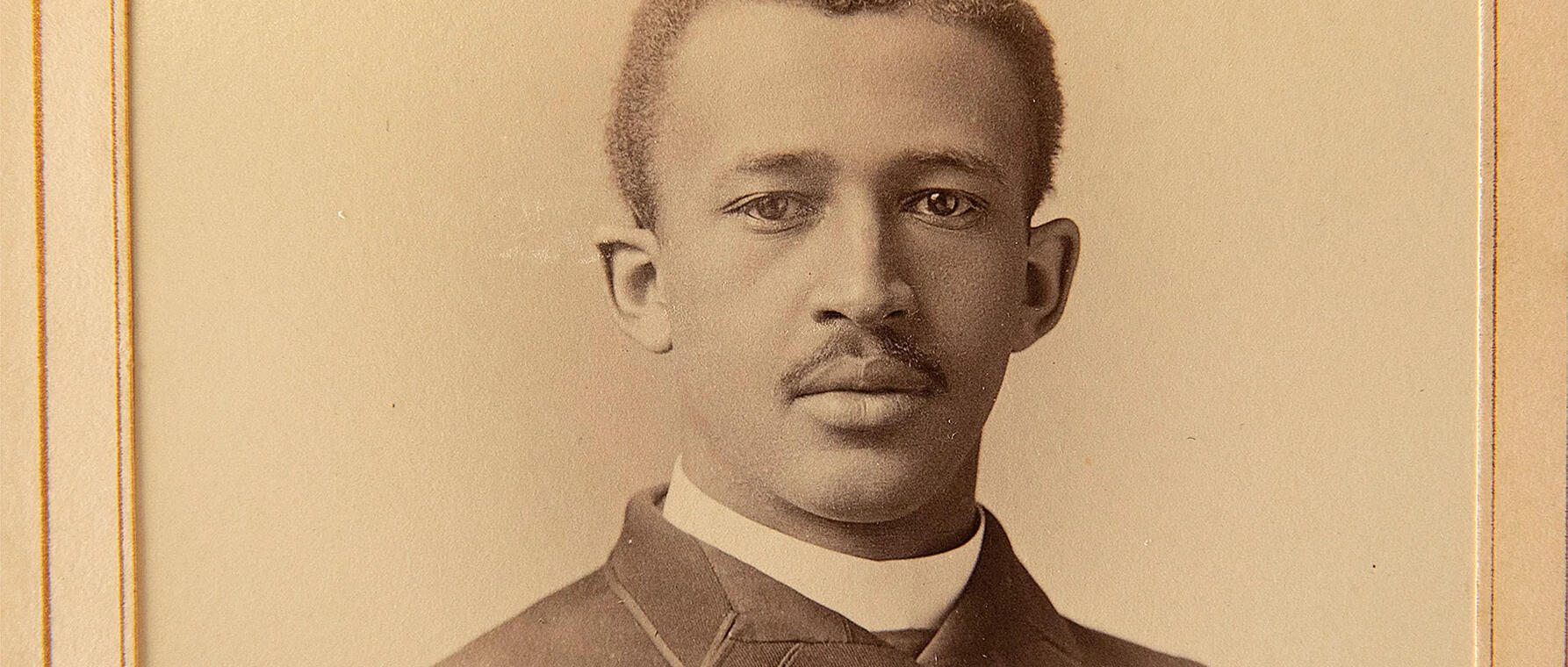

Only two years before, in 1895, Du Bois had become the first Black man to receive a PhD from Harvard. How did that experience shape the man who would become one of the leading Black activists and intellectuals of the 20th century? And what connections did he make in the vibrant Black community outside of campus? Join us as we explore these questions in the first of a two-part conversation with New York University professor and National Humanities Medal recipient David Levering Lewis, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for each of his two-volume biography of W.E.B. Du Bois.

The transcript below has been edited for clarity and correctness.

I want to get to your research. But first, a personal question: Your mother worked for Du Bois at some point. Did you ever meet him?

Yes, I did. My mother was a very smart young woman, a student at the first Atlanta University. And so when [Du Bois’s] studies were being made in 1908, 1909, and so on, she was just a freshman student. And so, it was a bit of vanity on the part of a mother to say I had an input in those who asked me to do something, and so I did.

But I did meet him. I met him with my father when he went before the Sigma Pi Phi—a professional organization hereditary, of African American men of achievement.

When was that?

1948.

In a recording he made toward the end of his life, Du Bois said that his years at Harvard were a time of great intellectual activity and a new freedom of thought and action. I wonder if you could just unpack that a little bit. Why was it such an exciting time for him?

It was the time of the presidency of Charles Eliot, and that was really quite revolutionary. It seems as we look back, for example, electives became the choice of the entering class; the compulsory chapel was certainly mandated. Eliot said in his inaugural address, I believe, that the University was no longer a finishing school for the wealthy. So, locals know it was a national institution, and therefore it was class-blind. And it welcomed all voices that could meet the merits of the opportunities on offer.

And it was certainly reflected in the new faculty. Santayana, a favorite of William James’s, had been hired just as Du Bois arrived. You had others who, and William James himself, who were returns from exploring something or other, with a new view of what ethics mean—a fascinating challenge to a temperament like Du Bois, who was so much an idealist throughout his life. I think fair to say, there was Hart, his finally, his major professor, Albert Hart, who had been there for a while.

Du Bois finished Fisk in 1888, June. And he, it seems to me, betrayed an idealism combined with force. That was really quite interesting in that his graduation speech was a tribute to [German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck]. In any case, it’s a new day at the University, with new people coming.

Du Bois actually entered the University as an undergraduate, even though, as you mention, he earned his bachelor’s degree from Fisk University in 1888. Why was that?

One should note that it was rather customary for the University to require graduates of even quite fine liberal arts colleges to repeat part of their trajectory in residency. And so Du Bois arrived in his junior year and will perform quite well. It’s a good time to be at Harvard. He will not be residential, however; he will live at 28 Flag Street for the duration of his residency—a house that still stands. But he took his meals at Memorial Hall.

Du Bois found William James immediately appealing. There is some debate about how close they were. Yet, I think the that day—date that I cannot identify precisely—that he and William James went together to visit the hearing-impaired Helen Keller suggests a kind of companionship, at least that must have been significant and significant in this way that Du Bois said that he was a regular of the Philosophical Club.

The Philosophical Club was anterior to the Metaphysical Club, which was more significant in this: had a number of scholars write about it, but to get to the metaphysical, you had to go through the Philosophical Club. And Du Bois says that he indeed was a regular. And there is a note from James saying something about “don’t forget the meeting Sunday or Monday or whatever”. And so I think so. And so philosophy excites Du Bois. It’s not surprising that he’s reading the Critique of Pure Reason [with faculty] and others.

You’ve talked about the relationships that Du Bois formed with University faculty, particularly philosophers like William James, Josiah Royce, and George Santayana. And yet Du Bois said that he never felt himself a “Harvard man” the way he was a “Fisk man,” and that he didn’t have a lot of relationships with his classmates. What was his experience of student life at the University?

Yes. Of course there was Clement Garnet Morgan, who was the other African American in the entering class of 1888. They were close. I don’t believe that they worked together at Lake Minnetonka to earn tuition. Du Bois arrived with Price Greenleaf [grant] money. But it was insufficient for the total expenses that confronted him. He inherited from his interesting grandfather, Alfred—father—a sum of money as a bequest. But it, too, was rather modest.

And the landlady at 28 Flag Street allowed him to pay as he could for residency. So it was hard duty in an environment of great quality—that is to say, financial security on the part of the overwhelming number, even though Eliot broadcasted it, the University’s doors were open to everybody. Not everybody could come. Du Bois was therefore a specialty, he thought.

Now, also, the old Harvard lived on, and many Harvard men were there because of their right to be there—their name to be there. But they welcomed a student who was so intense as was Du Bois. And I think that certainly was a bonding link with the faculty.

You said that Du Bois lived off campus. What sort of connections did he make outside of the University?

He found a community outside the Yard—a community very distinguished—that African Americans who, at a time when exceptions were the rule, really, distinguished lawyers, a woman who presided over a salon that Du Bois was regularly present at. I think indeed he inspired a lovely woman who later married the other Harvard man, as a matter of fact. And Du Bois always kept a relationship with that woman, Josephine Ruffin—I think her name was—presided over a newspaper of sorts, I think. So she was a protest feminist of great significance. And that was a learning experience for Du Bois, certainly. Not to think women were not also very modern. But here was a woman, really, who received the respect of the larger community, white and Black.

And then there were other African Americans at nearby schools who would pass through Boston and be present at the dinners and the salons. I think one of them was a man named Lewis, who they had finally in the first Roosevelt presidency, the curious designation of being the attorney general of New England. He had been a Dartmouth man who was a football player and later became a Bookerite. That is to say, his appointment was sanctioned by Booker T. Washington, which later would be an element perhaps there, interrelated. The Yard was very white, perhaps, but there was another one: Boston.

You mentioned in your biography of Du Bois that the curriculum at the University was transformational for him. Earlier in our conversation, you talked about the opening up of the curriculum and the opportunity to take elective courses. But are there other ways in which the coursework was particularly powerful in shaping Du Bois’s intellectual character?

Yes, because it wasn’t always a sunny day for Du Bois. And there were two courses in which he stumbled badly. One was Barrett Wendell’s famous class—was it English C or I? I perhaps don’t remember exactly what, but it was quite demanding. And Du Bois—and it was oversubscribed so that new people, new faculty were doled out the essays that had to be answered by these men.

And Lyman Kittredge had just arrived—a name in Shakespearean studies that still echoes, I think, to us. And Kittredge received a blue book answer from Barrett Wendell’s English class, and he exploded with “Egads!” “Egads!” as he read this substandard essay. And he said, “You know, you commingle so many thoughts that, yeah, there’s no lucidity, and you got to trim it back,” and what have you. And he got a C—his only C—that was devastating.

And so he struggled and improved. And Kittredge finally began to say, “Yes, the language now flows. That’s what we want; more of it”. But for a man who had such a gift at language, it’s worthwhile remembering that you learn to have that gift. It is not innate—perhaps for some people, but not even Du Bois. And so there was that.

Then there was the economics that he took seriously. But he later regretted, as you would expect, a Du Bois who becomes a Marxist. Frank Taussig and Economics 1—or whatever—was as capitalist-affirming as any professor could be. And so he soon thought that he had been blinded by Taussig’s economics, not to appreciate the labor movement, not to understand that when people succeed, it is perhaps because of the advantages that are part of the system. And all those things will come later.

Du Bois’s doctoral dissertation at the University was titled The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States. You call it monumental? Why? What ground did it break? And what aspects of his research and his writings stand out as a contribution to scholarship?

It is a monumental achievement. He did a number of things, and he made some connections that still are striking. He understood that the Haitian uprising had indeed changed American history; the attempt to suppress that uprising by Napoleon and the failure of it allowed slavery to prosper in ways that otherwise it might not have.

He is the first to say that without the Haitian Revolution, the American Revolution would have a different outcome. But the outcome is really that by preventing the reoccupation of Haiti by the French, it opened up the possibility of a delay in what seemed to be a momentum to have slavery go away. People in the North thought that it was not an institution that would be eternal. No. And so, in Massachusetts, in Connecticut, in states in the North, there were gestures legal for the emancipation of the enslaved. Usually you did not get it overnight; you had a period of service yet to fulfill.

But as Leon Litwack, I think, predicted it, the North would have been free pretty much of that institution. What happens, though, is quite the reverse—the ability of the South now, because of the Haitian Revolution and things that were consequential from it, like the purchase of the Louisiana, of the entire new area, which Thomas Jefferson called an “empire of liberty”. It was not to be that. It was to be the empire of slavery in which even whites would only serve as police power, perhaps, for this enormous expansion of that institution.

And so Du Bois sees that the 1808 closure—slavery from the transatlantic phenomenon—was a “fatal bargain,” as he calls it. Had it happened in 1798 and 99 with the convention—had they said, “No, no, we’re going to end it now”. But no, the Pinckneys from South Carolina, the Pierce Butlers from Georgia, Jefferson himself, with his hypocrisy—all of that resulted in the delay of the termination.

I believe, though, that Du Bois also thought that there was a greater input of slave traffic even after the closure—to go back, I think that he did not see that it would, by natural reproduction, continue to boom alone. But it is, it seems to me, his connection of political pusillanimity to Jeffersonian deviousness and the power of the slave South to delay this institution’s termination that was a tragic atrocity that would be ongoing and never, ever really be remediated.

Learn more about Du Bois's experience as a student—including why he thought himself “in Harvard but not of it"—at the Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery website.

Banner photo courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast