Of God and Globalization

Harvard Griffin GSAS Voices: Hillary Kaell, PhD ’11

Hillary Kaell is an associate professor of anthropology and religious studies at McGill University. Kaell discusses her work on Christianity in North America, conversations with Christians about climate change, and how her time at GSAS prepared her for a professorship at one of the world’s leading universities.

Christian Globalism

I’m an anthropologist of religion. I ask big questions about what it means to be human, to act in this world and with each other, and whether there are powerful, other-than-human presences like God. The response from my interlocutors would be to say that we never act purely as individuals and that there is an other-than-human presence—God, or the spirits of one’s ancestors—that guides us, provides help, and shapes our actions and futures.

In my research, I bring this focus on religion into conversation with another subfield in anthropology—multi-species studies—that examines how we can rethink human agency with respect to other living beings. What would it mean to see plants and animals acting as agents in the world, maybe even thinking?

I work mainly with North American Christians or people of Christian backgrounds who self-define as spiritual. I explore the way they adapt to and interact with different facets of globalization. In North America, Christianity is such an important component of society and culture, even for people who don’t go to church. It plays an immense role in what we think is normal, what is moral, what is good. Our institutions and laws and policies are affected by a historic Christian majority.

In my research, I think about the links between North American Christians who don’t travel much, or at all, and the rest of the world—how they think in global terms that are less obvious at first glance. I’ve looked at people who go on visits to Israel-Palestine and how they reckon with that experience after a lifetime of imagining the Holy Land from afar. I learned, for example, that pilgrims—most of whom are women—often understand the trip as tied to their relationships with people at home. Previous studies of Western Christian pilgrims assumed that motivations were very individualistic, mainly because no one had worked with pilgrims before and after the trips as I did.

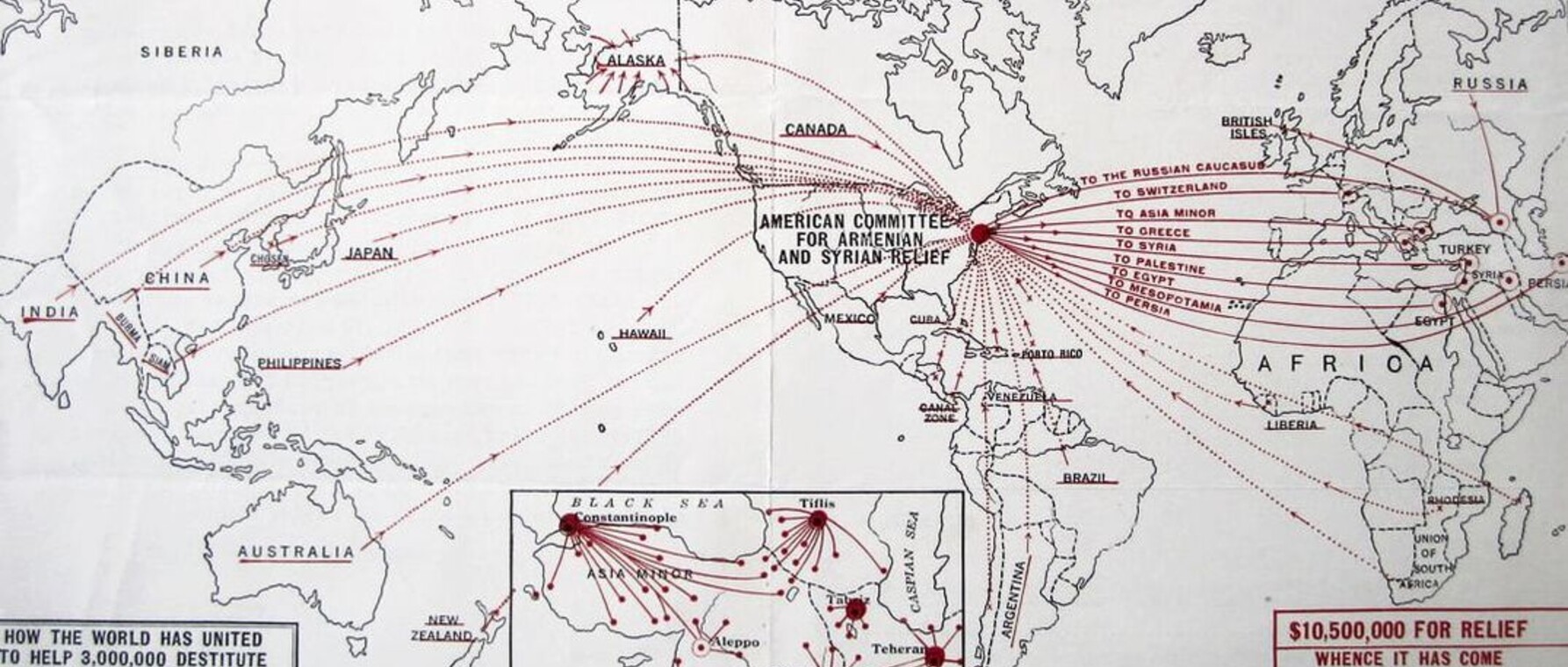

I have also studied how people give money to NGOs that connect them to faraway places despite never leaving their homes. I examined how global identities were forged through repeated practices that tacked back and forth between universals and particulars. For example, singing hymns over a globe to see the world as a whole followed by studying very specific facts about one child abroad.

Hurricane Path

I came to my current project because I was intrigued by hurricanes that start off the coast of Africa, make their way across the Atlantic, move through the Caribbean, and finally bump into the United States. We don’t think of the wind as operating on a global scale, but it does. Following it, I ended up working on barrier islands off the coast of North Carolina. What brought me there was how quickly the landscape could change, particularly in the context of a hurricane. There are also a lot of Christians and places of Christian worship on the islands.

I am trying to create a properly complex picture of the shifting ecological landscape there. To do that, I involve a lot of humans from different backgrounds—from local fishers and coastal scientists to migrant laborers and mold experts—alongside the other-than-humans that matter to them, like plants, animals, microbes, God, the spirits of the dead, and the spirits of their ancestors. So, for example, I’m following a project to build a “living shoreline” that uses intertidal grass to control erosion.

One of my goals is to nuance the conversation about religion and ecological change beyond broad surveys that ask US Christians if they ‘believe’ in climate change or not.

To get a holistic sense of it, I include in my description of events the role of humans—contractors, coastal scientists, volunteers—and non-humans—such as the grass, a snail that lives in situ, and oysters. I also include other-than-humans that people involved in the project have told me are present: God, a deceased loved one, and spirits that inhabit the plants. One of my goals is to nuance the conversation about religion and ecological change beyond broad surveys that ask US Christians if they “believe” in climate change or not.

Ecological degradation is such a pressing issue. Our planetary future is at stake, and I hope more academics across a variety of fields will incorporate relevant questions into their research. Humanistic and social science research can make an impact on how we think about our past and present—and thereby open new possibilities for imagining the future.

Kindness and Rigor

Harvard was a culture shock for me. I had never lived in the US and I had also never been at a private university like Harvard. It was difficult for me at times but it also got me excited to bring what I learned back to my home country of Canada and the public institutions there.

Religious studies was a completely new field for me when I came to Harvard. I hadn’t worked on Christianity so I had to master new topics. I was struck by the fact that a lot of the work on globalization and Christians had to do with what we might think of as the usual suspects: missionaries, pastors who were traveling abroad, and migrants. It had a lot to do with borders and human movement across borders. In my work, I try to include voices—and species—that go beyond those actors.

The kindness and the rigor of the professors on my committee and the general examination process shaped me into the scholar that I am today and gave me a base from which I could move forward. Even today, many of the books and articles that I read during my time at Harvard are the same ones I assign my students as a professor.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast