Facing African Art

Tracing the connections between art's makers and ourselves

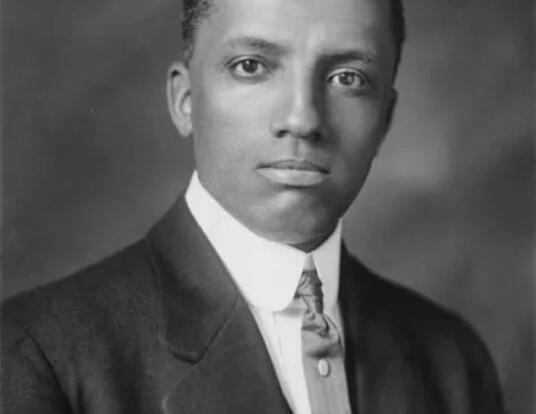

As an undergraduate at the University of Vermont in the late 1960s, Suzanne Preston Blier heard an idea in her very first art history class that cemented her vocation in the field. It came from the great art historian Erwin Panofsky. “In his eyes, everything had a symbol and a meaning, and you could go into a work and decipher it,” Blier says. “It’s like being part of, and also writing, a detective novel.”

It’s appropriate, then, that Blier, who happily cites Nancy Drew novels as one of her life’s inspirations, thinks of herself as a sleuth. Her specialty is African art — a field in which art historians do well to bulk up on forensic skills. Africa is the cradle of humanity; its art is as old as its cultures. But objects that date back before colonial times — and even some that are more recent — come to museumgoers, collectors, and students bereft of much key information. We are given, perhaps, a time period, a region, an ethnicity. But who made the work? Who paid for it? What events surrounded its making?

With little to no written history to turn to — most precolonial African civilizations transmitted knowledge orally — art history for many years essentially threw up its hands, says Blier, the Allen Whitehill Clowes Professor of Fine Arts and professor of African and African American studies. “When I grew up in the field, we focused on works created in the late 19th through mid-20th centuries,” she says. “And it’s a fabulous field. But for the most part, people were not going back in time.” She heard of eminent scholars, pleading the lack of data, saying: Leave it to the anthropologists. It can’t be done.

But Blier had an edge. She’d been to West Africa — to Bénin, with the Peace Corps, before she even completed her bachelor’s degree — and she knew instinctively that its early art deserved better. “I’m a terrier,” she says. “I grab onto something like that. I had fallen in love with Africa, and I decided to dedicate my career to African art history and try to transform it.”

Mission accomplished. Blier, who came to Harvard in 1993 after teaching at Columbia, is not only one of the most honored historians of African art practicing today, but also one of its broadest thinkers. Her books encompass not only issues of form and aesthetics, but also architecture, psychology, representation, and philosophy. She has immersed herself in multiple West African cultures — the Yoruba of Ile-Ife, Nigeria; the Battamaliba of northern Togo; the Abomey kingdom of Bénin — as well as followed the trace of African art as colonialism and commerce scattered it into the West, along the way picking up leads that tell us much about not only art’s makers but its viewers — ourselves.

This year alone, Blier has four books appearing or near completion. They address the spectacular bronze and terracotta sculptures of Ile-Ife and what they tell us about Yoruba civilization circa 1300; the Amazon women warriors of Dahomey (now Bénin) and their representation in the West, including travelling shows at international exhibitions in the early 20th century; and, in a characteristically creative sidebar, a fresh contribution to scholarship on Pablo Picasso’s famous — and at least partly Africa-inspired — Demoiselles d’Avignon.

At the same time, Blier has revealed her techie side. In 2009, she launched AfricaMap, a Web-based tool that allows rich sorting and visual layering of all kinds of existing data: social, environmental, political, economic, historical, linguistic, and so forth. Its success led to an expanded platform, WorldMap, that launched in 2011. Hosted by Harvard’s Center for Geographic Analysis, but open-source and freely accessible to all, these platforms open new horizons for research, teaching, and interactive presentation of ideas to any audience, and for collaboration across locations and fields. As co-chair of AfricaMap and head of the WorldMap steering committee, Blier is the rare art historian blazing trails in technological innovation for all disciplines.

Blier’s work on the Ile-Ife sculptures — a project she began almost 30 years ago and pursued, she says, with the doggedness of a “military campaign” — exemplifies her methods, and also her ambitions. The bronze and terracotta sculptures she considers are, in one sense, well known. They are naturalist masterpieces, so refined and realistic that the German archaeologist Leo Frobenius, who unearthed the first one to come to light in 1910, believed that they could not be the work of Africans. Instead, he speculated, they might have come from the lost kingdom of Atlantis. That theory quickly lost currency, but the figures retained their mystique, anchoring a major exhibition on Yoruba art that toured Britain, Spain, and the United States from 2010 to 2012.

Yet in another sense, these pieces remain unknown — “a challenge to decipher,” as one reviewer wrote, due to the lack of documentation and their provenance from “sites altered over time, resulting in a compromised archeological record.” But Blier took a different starting point. Ife, she notes, is one of the world’s oldest continuous kingships. “One thing that fascinated me was, how does that kind of longevity happen? And how are arts embedded in that society?” Waving aside the lack of written record, she spent time with the objects themselves — in Nigeria, at the British Museum in London, and elsewhere — seeking clues in their materials. Some were pure copper, some were various alloys, resulting in different hues and textures that could convey separate meanings. She immersed herself in Ife, interviewing families that live at the archeological sites, teasing out histories. She connected the period when the key bronzes were made to the aftermath of a brutal civil war in Ife and that war’s stakes, to do with resources and control of trade routes with other African states and across the Sahara. She began to know more about the artists who made these works at massive furnaces — possibly sealing their own death by the use of arsenic — and Obalufon, the king who commissioned them.

Blier’s forthcoming book on the Ife sculptures is titled Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba. “There was enormous risk in manufacturing these life-size bronzes, enormous potential for failure,” she says. “And the risk that people take who have been involved in a great tragedy, such as this civil war: they feel a compulsion to tell it through their arts and their oral literature, so that people know what went on. You can see comparable things in the aftermath of the Holocaust, or the slave trade: this thirst for people to know the story.”

Who tells the story is of course a fraught question when it comes to African culture and arts, where colonial explorers, agents, and scholars have done so much of the talking. Another forthcoming Blier project, Imaging African Amazons: The Art of Dahomey Women Warriors, is as much about Western interpretations of these all-women brigades, which go back to the 17th century, as it is about the warriors themselves. In Abomey, Bénin, Blier became fascinated with a palace bas-relief depicting these Amazons, who were often the first to go into battle. “It shows them doing the devastating work,” she says. “Killing, taking objects, taking slaves.” The Amazons were often captives taken from neighboring kingdoms; Dahomey, where the Vodoun religious system that is now associated with Haiti originated, was heavily involved in the slave trade.

By the late 19th century, with the kingdom fallen and colonial rule entrenched, the Amazons had become the object of European fascination and fantasy, freighted with conceptions about race and sexuality. At the turn of the century, groups of them actually toured and performed at colonial exhibitions in Europe, and also in the United States, where, Blier says, “their guide was a Frenchman who was also involved in contract labor to build the Panama Canal.” Each audience imbued these women with a meaning — about colonialism, military discipline, and more — that reflected local concerns. In America they got portrayed as cannibals and savages, undermining calls for racial equality. “It became about slavery and Jim Crow,” Blier says. “And it’s about women’s rights, women as cannibals and agents of destruction, and God forbid we should give women the vote.”

Blier happily concedes that projects like this spill beyond the borders of art history. “I’m interested in how images construct the world, and also in how the world in which images are made constructs those images,” she says. Looking for clues in geology, economics, or any other discipline is fair game — indeed, it’s necessary. The AfricaMap platform integrates databases on everything from religion to commerce, disease prevalence, climate, and conflict history, making this kind of cross-discipline work feasible, not overwhelming. Blier says it has revolutionized her work, allowing her to collaborate with other scholars and perform fascinating new analyses. “Simply locating people in space is central to my research,” she says. “I’m looking at DNA, architectural forms, trade routes, water availability — it’s taking me into areas I never imagined I would be able to explore.”

Blier thinks big, but she’s just as excited by the small revolutions in academic labor — the way that patient scholarship, and a touch of serendipity, can present an old topic in a whole new way. She lights up when she evokes her forthcoming Picasso project, Decoding Picasso’s Demoiselles, a re-reading of the famous painting in light of material Blier found that, she is certain, influenced Picasso at the time. She is coy, for now, about the details, but gives a hint: “Africa is being brought back into the story of the ‘Demoiselles’ in a central way,” she says. “Picasso had close sources. And he was far more engaged than we have assumed with the major issues of the day.

“This is sort of my late-life love child,” Blier says of the Picasso project, laughing. But it illustrates a theme: from her base in the supposedly obscure and difficult domain of pre-colonial African art, she has presented ideas and developed tools that speak not just to art history as a whole, but to many other fields. “I’m viewed as an Africanist,” Blier says, “but that has given me a huge amount of freedom to come back to central issues and re-engage them in ways that others have not done.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast