Clear Identity

How Kristina Olson’s TransYouth Project is overturning expectations about gender.

Imagine you wake up one morning, certain of who you are and of your place in the world. You are a boy or a girl, with the likes and dislikes associated with that gender. It doesn’t occur to you that you should be any different, or even that you could be. You are who you are.

Then, imagine you get up and look in a mirror, surprised to see a body that does not correspond to the person you are certain you are. You feel trapped in some kind of Kafkaesque reality: The body you inhabit is the wrong one, the opposite one. What do you do? What can you do?

Understanding the Under-Understood

The experience of not connecting with the gender assigned at birth is referred to by the medical community as gender dysphoria, though people who fall into this category often prefer the term transgender. Statistics vary, but a 2017 study in the American Journal of Public Health estimates that 1 in 250 Americans—a total of 1 million people—identify as transgender. It predicts that more-robust studies in the future will find the actual number to be much higher.

Transgender individuals don’t merely deal with a disconnect between mind and body. Many also contend with families and a society that often don’t understand what they are going through, facing high rates of harassment, bullying, and assault. Many live with high levels of stress, isolation, and mental health challenges and often contemplate or attempt suicide. In fact, a survey of nearly 6,500 transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force in 2011 found that 41 percent of respondents reported attempting suicide compared to 1.6 percent of the general population.

We don't know what will happen as the kids get older and move into adolescence. But for now, it seems like most of those who socially transition are very clear about their identities.

–Kristina Olson, PhD '08

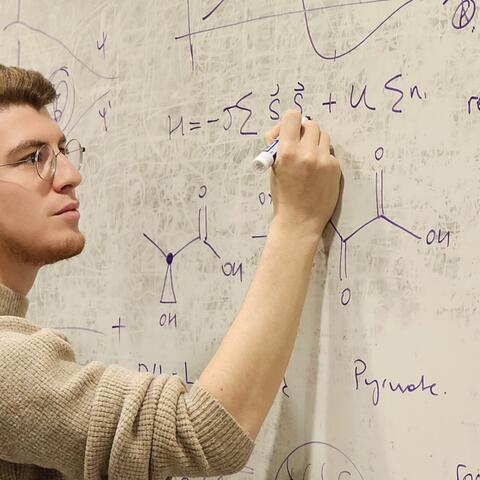

But is it a given that individuals who identify as transgender will necessarily face these challenges? And what role, if any, does nurture and environment play? These questions form part of the work that Kristina Olson, PhD ’08, is addressing through the TransYouth Project, the first large-scale, longitudinal study of transgender and gender-nonconforming children.

“Part of what drew me to study the experience of trans kids was an interest in understanding groups that are under-understood,” explains Olson, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Washington. “Transgender people have unequal outcomes in the world, but at the time I started the project, very little work had been done, especially regarding transgender children.” In many ways, the scientific community had marginalized the study of an already marginalized group, which made the transgender population all the more interesting to Olson. As a developmental researcher, she is intrigued by the dynamics at play when society actively discourages individuals from identifying with a social group to which they feel an affinity.

In her work more broadly, Olson is interested in how children divide the world into social groups and how they think about inequality. “At an early age, children seem to divide the world into people like them or around them and people who are different,” she says. “Your society tells you what kinds of differences matter.” These dichotomous categories—boy or girl, rich or poor, white or not—can become powerful markers for inclusion and belonging on the playground and, if left unchallenged, can be used as tools of exclusion in the adult world.

Through the TransYouth Project, Olson is following 300 transgender children over 20 years. These are children who have socially transitioned at early ages—that is, they are living as a gender other than the one assigned at birth—with the support of their families. “I’m interested in what gender identity development looks like in this unique cohort,” says Olson. She wants to understand how the children think about their gender and track whether their thinking changes as they move through adolescence and adulthood, and as society changes. Given the health challenges often seen in transgender adults, she also focuses on her subjects’ well-being and mental health.

Overturning Expectations

In the United States, the importance of a child’s sex seems a given. Parents-to-be consider whether or not to find out if their baby is a boy or a girl, and often the first words spoken after the birth are “It’s a girl!” or “It’s a boy!” Children who identify differently are thought to be confused or oppositional. Olson has found that the reverse is true.

“The kids that we’ve studied are very insistent about their identities across a wide range of measures,” she says.

“Our results suggest they largely think of themselves in a very binary way, like many non-transgender kids do. For example, on our measures, a transgender girl looks just like any other girl.” These results counteract the idea that a child is pretending to be another gender as a part of imaginative play as, for example, when a child engages in make-believe by acting like a cat or a dinosaur.

So far, most of the children in the study have remained consistent in their gender identification as they’ve aged, though Olson notes that gender can evolve over time. “We don’t know what will happen as the kids get older and move into adolescence,” she cautions.

“But for now, it seems like most of those who socially transition are very clear about their identities.”

Further Reading:

Philosophy candidate Clarisse Wells brings Indian philosophy to the study of race and gender.

Olson’s initial results related to mental health, too, overturn the expectation that transgender individuals face greater challenges. “So far, we’ve found that our kids have pretty good mental health, much better than most studies of trans adults and teens,” she says. But she adds a note of caution: “Children can’t socially transition without their parents’ support at these ages, and the families we work with tend to be very supportive. We certainly want to be cautious about whether these results generalize to children without this early support.”

Fluid Identities

More recently, Olson has expanded the project to include not only children who identify as either a boy or a girl, but also those who think of themselves in a nonbinary or more fluid way. “That’s the group we’re most actively recruiting right now,” she says. “Even though we have very little information about transgender kids, we know even less about kids whose gender shifts over time or who don’t fit into one gender or the other.” Olson believes there is a great deal to learn about these children, and she wonders whether some who currently identify with a particular gender will ultimately develop a more fluid identity or one that is more in the middle. “That’s why it’s important to follow them as they grow,” she says.

The response to the TransYouth Project has proved polarizing. But the importance of the work has been underscored by the number of awards Olson has received since initiating the study: the 2016 Janet Taylor Spence Award from the Association for Psychological Science for transformative early career contributions; the Alan T. Waterman Award from the National Science Foundation in 2018; and in fall 2018, a MacArthur “Genius” fellowship.

“When you study something where public opinion is changing rapidly, of course you’re going to get people who think it’s a great idea and people who are not so enthusiastic,” she says. “Certainly, some say that this issue didn’t exist when they were young.” But, remarkably, as she gives public talks about the TransYouth Project, she meets people in their 70s and 80s who only recently became comfortable enough to share who they really are.

“They tell me that when they were young, they knew two things: that they were a girl and that they would take that knowledge to the grave,” Olson says. “They say, ‘I cannot believe I am alive to see a time when research is being done on this issue, where children are having such a different life than I had.’”

Photo courtesy of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Illustration by Julia Breckenreid

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast