Colloquy Podcast: African American Encounters with Property and the Long Shadow of Slavery

In advance of Juneteenth 2024, a conversation with University of Texas Professor Shirley Thompson, PhD '01, author of the forthcoming book No More Auction Block for Me, about how the experience of being treated as property has shaped the way that African Americans understand and relate to property themselves. Acknowledging the trauma of racism and white supremacy, Professor Thompson looks at the ways that community, creativity, and resilience enabled Black folk to assert their humanity in the face of objectification.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and correctness.

Shirley Thompson, how did race and property become so intertwined?

Thanks for that question. The short answer is they're interwoven because of the history of racial slavery, the commodification of Africans and their descendants, their subsequent transportation across the Atlantic as commodities, and their sale into slavery in the Americas. All of this yokes together the concept of Blackness as a racial category and a status as an article of property in the practice of enslavement and the slave trade.

In the territories that would eventually become the United States, the entanglement of Black racial identity and property status becomes institutionalized really early. In the mid-1600s in Virginia, you get a series of laws passed, which are race-based and they bind people of African descent laborers—well, they distinguish them from indentured servants—and then make those categories racial. They bind Black enslaved people to their masters for life and then bind their children and their children's children to this long line of masters who will own them. So it's the racial nature of that distinction between indenture and slave that begins to tie the status of slave to the identity of Blackness.

The kind of binding you describe, lifelong and then in perpetuity, down through generations, is that one of the things that distinguishes American slavery from other types of Western European slavery throughout history?

I would say there is some distinction between different colonial regimes at the level of law. The Spanish regime, for example, had a lot more provisions for manumission and self-purchase. However, how colonial law looks from the level of law on high and practice on the ground is very different. Often on sugar plantations, which was the dominant plantation in Latin America and the Caribbean, the work was so grueling and brutal that people didn't actually live more than a few years anyway.

How is the relationship between race and property embedded in the US Constitution?

Deeming enslaved people three-fifths of a person, you build that tension and relationship into not just the legal status but in the experience of enslaved people that gives them recognition for being persons in three-fifths of their body, and then they're consigned to the status of property in the other two-fifths of their body. And so there's a tension, a conundrum, I think at the basis of Black being in the US context and in other contexts, but the US's Three-Fifths Clause is particularly suggestive of that tension.

And then in practice, that tension can be drawn on or expressed to emphasize one aspect or the other of that personhood or property status. So when the Supreme Court rules in Dred Scott versus Sanford, Judge Taney is able to say that Blacks have always been considered items of merchandise. They have no rights as persons. So he can lean into that property designation and thereby erase the personhood elements as well.

So my research focuses on the period in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—a generation removed from formal enslavement—to look at the emergence of Black institutions, Black sociality, African American attempts to protect themselves and extend mutual care to each other in an effort to extend their lives as far into the future as possible.

How did the relationship between race and property change and develop in the late 19th and early 20th centuries after the abolition of slavery?

One of the earliest sites that I've been looking at—and this an example of the kind of questions that I hope to continue asking in this book—is African American life insurance companies that grow out of mutual aid societies and eventually transform themselves into mainstream corporate entities offering insurance, life insurance, to African Americans. So this is an example of Black capitalism, of how African Americans try to build institutions that will allow them to participate in these really important financial markets and to tap into the kind of potential, an economic potential, that exists within African American communities.

The thing about life insurance is that it measures people—the kind of actuarial method is to measure each individual according to a standard, and that standard was very racialized in the emergence of this industry in a way that valued whiteness and white maleness, in particular, and devalued people who didn't measure up to that standard. And Black people were considered too risky to insure. And you can see why that is the case because they're being faced by white supremacist violence in this period— lynching, rape. You don't have access to healthcare. You could do a very objective analysis of lifespans in this period and come up with the same calculation.

That said, African Americans have always had traditions of mutual care in order to create some community safety nets for each other to tap into if people needed money or help or anything, such as burial insurance. There are these informal networks and practices that have been in place. You could argue before the transatlantic slave trade and emerging out of the transatlantic slave trade that people banded together in ways that they were able—in the completely inadequate ways that they were able—to provide safety and comfort for one another in those circumstances.

You mentioned that mutual aid societies were the precursors to Black life insurance companies. How did they work?

As a means of providing for one another and establishing mutual trust among one another. They pool resources so that people in dire straits could tap into those resources when they needed to. And it's not unique to African Americans, obviously. There are other immigrant communities that establish these informal networks of care that connect communities, people who are more than family but less than strangers, in these often-secret associations.

Or they have elaborate rituals that solidify that trust and can often look like a secret society, but the function is to provide mutual care and support. At some point in the early 20th century, there are a number of laws that are passed that really constrain these informal associations, and a number of them scramble to try to find ways to reconstitute themselves. And so what I found with a lot of Black insurance companies is that they have their origin in leaders of mutual aid organizations reaching out to them—to business leaders, to people with capital in the community—to ask them to help them reconstitute themselves in a way that will conform to these new laws that are forcing them to look more like small insurance companies.

And from there, these Black institutions begin to build themselves up to develop so-called best practices and really expand what they're able to do to make these smaller concerns more large scale until they eventually look like mainstream insurance companies. In the process, though, they begin to diverge from the mutual care model and reinforce some of the same violence of commoditization of human life, making people fit the numbers, those kinds of things that echo the same logics of enslavement.

So that was my next question. Once these companies started to emerge, to what extent were they breaking through the systemic racism that dominated the insurance industry? And to what extent were they reproducing it?

They do both in a way that sometimes cancels out their goodwill and their good intent. But in some cases, they're able to tap into the original mission and extend it in spite of what the market demands are.

For example, Atlanta Life, one of the largest of these companies, created a foundation within its company structure that acted as a fund that would support racial justice projects. It was one of the main funders of the defense of the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s. So there's a mixed legacy there, but more than that mixed legacy, there's also ways in which informal practices or even oppositional practices to this market-based mutual care still continue to be a strategy—an important strategy for ordinary people in their communities.

So people did things like play the numbers. They often used their insurance policies in ways that insurance companies didn't intend for them to use by using them as credit, drawing on their policies for cash when they didn't have cash. So I'm trying to think about ways people maintain their dignity around the institutionalization of property in spite of the indignities that those kinds of practices carry with them.

You mentioned the attempts of Black folks to preserve their dignity in the face of a system that objectified them. What role did expressive culture play in that struggle?

Expressive culture, literature, Black expressive culture is a fraught set of practices that are continually trying to outpace efforts to appropriate them. And I'm talking in vague terms, but I'm thinking of things like the recording industry and how the attempts to capture Black speech and the Black singing voice or Black dance or Black music or other kinds of expressive culture and to appropriate it, to enclose it and make it available to the market, and how Black expressive culture is continually trying to be a step or two ahead of that process in defying those market logics but also still trying to make a living. So Black artists are in continual struggle with this process that seeks to strip them of ownership of their own bodies, of their own creativity. So it's this fugitive relationship, this fugitive process.

So let's take Black Swan Records, a jazz and blues label founded in 1921 by Black entrepreneurs Harry Pace and WC Handy. Was a company like that ahead of the curve or riding it?

That's the tension that I think I'm really trying to explore, and it's the same tension that I find in the insurance company example, which is in order to participate in this market, you accept some of the practices. And not only that, but the way in which race or the expression of the Black voice signals potential value is something that whether you're Black Swan Records or Atlantic Records, you're chasing the same value.

What about the artists themselves? Your first book was about New Orleans. That's the birthplace of jazz music. By the time Pace and Handy are making it big, jazz has spread to big cities around the country and it's starting to sell records. How does the music try to stay ahead of the commodification? Does it?

Well, I would go back to the streets of New Orleans and the larger communities to which the music is responsive and accountable. These mutual aid benevolent societies that I've been talking about is forming a network of mutual regard that conveys dignity to or are established to maintain the possibility for dignity for African Americans. These mutual aid societies are very closely bound up with the production of music and the creation of new music and new musical forms and contexts in which that music makes sense and in which that music begins to evolve to meet the needs and to express the tastes of that particular community.

So while all this is happening in the recording industry, none of this puts an end to the context for making music in New Orleans, the second lining, the funerals. So I think New Orleans is a great incubator for thinking about these issues or thinking about how Black expressive artists have challenged these market logics because the music continues to function in these non-market ways, in these communities of care and support in ways that fly under the radar of the music industry, of these national and global companies.

And I would say that continues. You can chart the evolution of this music through various genres in New Orleans. So whereas jazz is institutionalized, you get communities there forging new forms and ways of playing music, ways of singing, ways of dancing. You have a strong tradition of New Orleans funk music, R&B, and then hip-hop and bounce music that has recently become popular but had function in New Orleans long before its national popularity as a lingua franca in some ways for people in relation to one another in New Orleans.

Without historicizing, is there a way to make some observations about how race and property continue to be interwoven in our society and culture today?

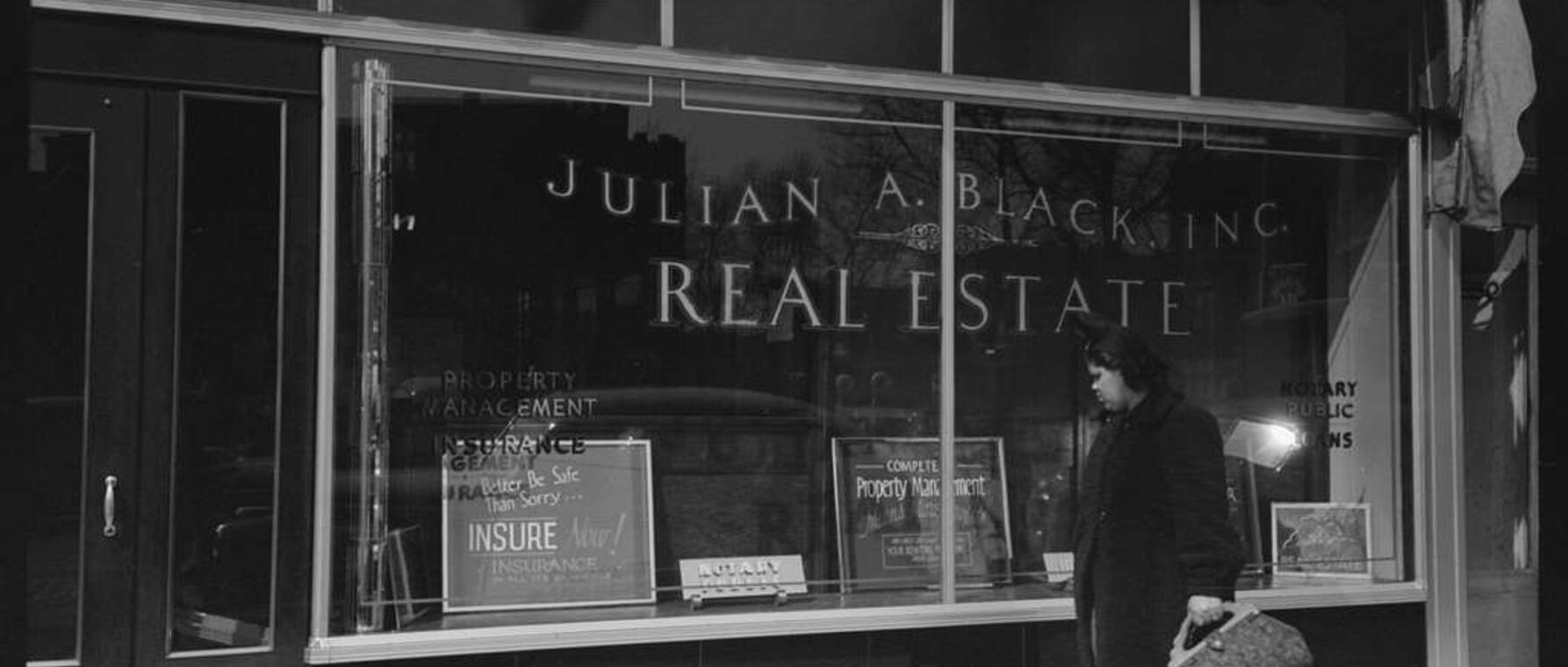

Yeah, I think a lot of people have done a lot of really interesting recent work on the real estate markets, especially in the aftermath of 2008 and the mortgage crisis and how that devastated Black communities, Black property ownership, in places where a lot of African-American wealth was bound up in real estate, and that crisis erased a lot of that.

But I think charting real estate, the ebb and flow of property value through the movement of racialized populations, is very revealing. For example, thinking about suburbanization in the 1950s—'40s and '50s—and how that created value for white property owners but threw up all of these barriers for Black access to mortgages, to suburban homes, because they were forcefully kept out and also because they were economically not able to invest in those properties, and how that whole process in the aftermath of World War II set the wheels of inequality and just amplified practices that had been longstanding to keep Blacks confined to certain regions and then to devalue the property within those spaces.

This suburbanization moment just injected those longstanding processes with steroids almost and then set in motion this larger and more deeply unequal real estate regime that you can trace and see the ebbs and flows happening. When Blacks move into a neighborhood, you have white flight and that sets in motion the deflation of property values in the neighborhood. And so it's a series of cycles.

Finally, Austin, Texas, where you live and teach, is one of the hottest real estate markets in the country right now. How is the relationship between race and property playing out right in front of you?

City ordinances, the restructuring of zoning laws, all these things work to favor developers who then come in and deem these previously so-called blighted or sketchy areas ripe for reinvestment. So there's an economic and political set of decisions that put these processes in motion, and, yes, African Americans are the first to go. In fact, I have some colleagues here at UT Austin who looked at this phenomenon as it was really getting underway in early 2010 and noted that among all the very rapidly growing cities in the country, Austin was the only one that was losing Black population. People were fleeing to nearby suburbs and nearby towns and couldn't afford to live in Austin anymore because that property, which is in town or close to downtown, all of a sudden began to look attractive.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast