China by Way of Cambridge

Michael Cerny, PhD student

Michael Cerny is an incoming PhD student who studies US-China relations. Cerny discusses the changes in the two countries’ relationship over the past decade, his path to Harvard Griffin GSAS, and his plans to frequent Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies.

Confrontation and Competition

Over the past decade, a stunning shift has occurred in how the Washington foreign policy establishment views the Chinese state, its ruling party, and its relationship to the United States. My research seeks to understand how we got here.

The US-China relationship has waxed and waned between confrontation and reconciliation over the past seven or so decades. When the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, Washington was dominated by fears about the balance of power with the Soviet Union and its communist allies. Consequently, the relationship between the US and China was at first defined by hostility. As the relationship between the Chinese and the Soviets began to unravel, it created an opportunity to establish US-China relations, which were productive for many years.

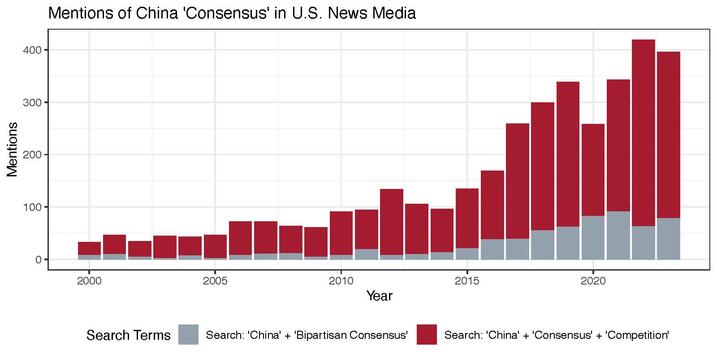

Over the last 10 or 15 years, however, US-China relations have experienced a downturn characterized by confrontation and competition. Some even worry about the prospect of violent conflict. Many see three forces driving this downward trend: the changing balance of power between the two countries, China’s political and ideological challenge to the US-led international system, and the alleged failure of previous policy to “liberalize” China and shift it away from single-party rule. Intrigued by the emerging “consensus” on China among policymakers, my research with [Princeton University Professor] Rory Truex examines whether professional and social dynamics in Washington might encourage policymakers to adopt more confrontational attitudes toward China. We hypothesize that US policy might not accurately reflect the broader debate on China’s behavior and might therefore encourage greater confrontation.

At Harvard, I hope to continue this research by examining the decision-making environment in Washington and Beijing, such as how institutional and staffing changes may have contributed to this shift in bilateral relations.

A Chance to Learn from the Experts

When I arrived at Emory University as an undergraduate, I bumped into Tonio Andrade, a professor of history, whose book on Chinese military innovation I had read in high school. We got to talking, and he strongly encouraged me to enroll in Chinese language alongside my political science major to effectively study the US’s most consequential relationship. Convinced, I enrolled later that afternoon. I eventually studied abroad and conducted research in China, which was a fascinating opportunity to get direct experience with the country—from surveillance in everyday life, to the university system, to the perspectives of Chinese citizens. That firsthand insight is hard to develop from the outside.

After graduating from Emory, I continued my study of Chinese politics at the University of Oxford and eventually started working and researching at the Carter Center. All of my experiences led me to appreciate how much Cambridge and, specifically, Harvard is a premier place to study China. I’m particularly looking forward to spending time at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. The center invites researchers to speak on topics ranging from the history of the Opium War to the current status of US-China relations. There’s just a huge range of scholarship. I’m excited to learn from the experts who converge at the Fairbank Center—including those who work directly on Chinese politics and US-China relations.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast