Beyond the Dogmas of Life

José Del Río Pantoja, PhD Candidate

José Del Río Pantoja is a PhD candidate in chemical biology at Harvard Griffin GSAS. A member of the Mostoslavsky Lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, he is challenging long-held assumptions about the way proteins are formed in cells—and uncovering how missteps in that process may underlie disease. Del Río Pantoja reflects on his unexpected path to a PhD, the mentors who shaped his journey, and the power of rest in scientific discovery.

Parsing Proteins

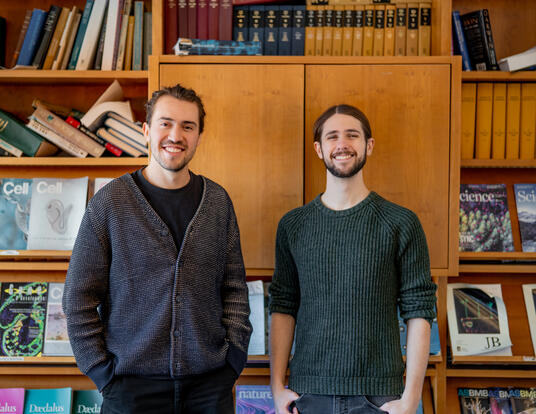

I’m now a member of the Mostoslavsky Lab at Massachusetts General Hospital under my advisor, Raul Mostoslavsky. Raul is Argentinian and the most supportive person you could meet. He gave me the space to do the kind of science I believed in and most enjoyed doing—basic, foundational, and bold.

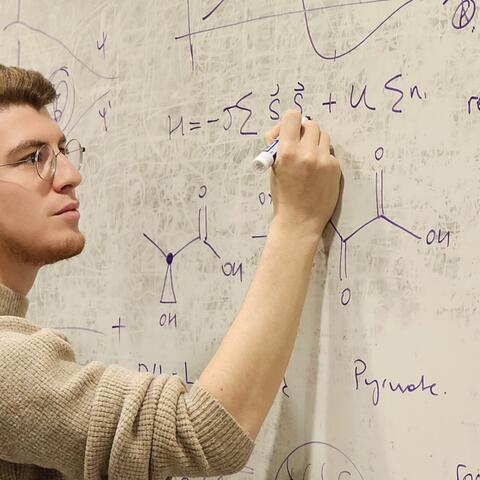

Canonically, biology follows the “central dogma”: DNA makes RNA, RNA makes proteins. And if you know the DNA sequence, you can predict the amino acid composition of the protein it encodes. But I had a hypothesis that pushed against that idea. What if proteins can contain more amino acids than are actually encoded in their DNA? What if the coding sequence of a gene isn’t the whole story?

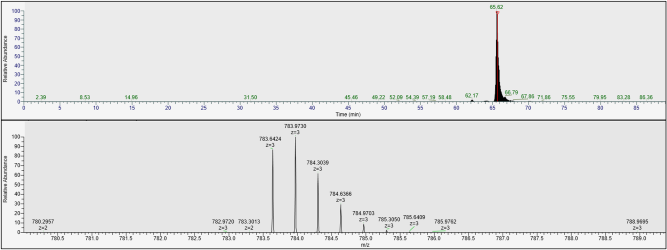

I proposed a project to detect proteins that have these additional amino acids. To our surprise, it worked. We found many examples in human cells. Now, the first part of my thesis focuses on the technology we developed to detect these additions. The second part asks why they happen. We’re finding that the process—evolutionarily conserved all the way from bacteria to humans—may help control how proteins are made, stabilized, and broken down.

Even more exciting is the link to disease. We’re discovering that certain cancers and some inherited retinal dystrophies are sensitive to disruptions in the enzymes that add or remove these extra amino acids. In other words, this novel process isn’t just happening in healthy cells—it may be going wrong in disease.

One of our big questions is: What exactly happens in these diseases when this regulation is disturbed? If we can figure that out, we may be able to target it and offer better treatments or care.

“Life Is the Bubbles, Under the Sea”

I changed labs in the middle of my PhD. It was a tough decision, and one I made with the help of my closest friends and Dr. Sheila Thomas, then dean for equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging at Harvard Griffin GSAS. Sheila was a true mentor. She helped me see that switching labs wasn’t a failure—it was the right step for my growth.

Raul welcomed me without hesitation. Maybe it’s our shared Latino background, but he’s become like a work father to me—caring not just about my science, but my well-being. He gave me room to think creatively and the connections and support to make my vision a reality.

In my time in Raul’s lab, one of the most important lessons I’ve learned here is the value of rest. I used to think productivity meant constant work. But the idea that led to my assay for detecting extra amino acids? That came while I was watching The Little Mermaid in a movie theater. I saw the bubbles in the water and thought of hydrogen bonds and ion-dipole interactions. That spark led to the method we use today. Now I see rest as a vital part of my scientific process. When I’m calm, ideas come more easily. I sit with a cup of iced coffee, let my mind relax, and the answers start to form.

A Change of Plan

I was born and raised in Vega Baja, a town on the north central coast of Puerto Rico. My mom stayed at home with my three brothers and I—though she had a science degree, she never practiced—and my dad was a business-minded entrepreneur known for making things happen. I like to think I inherited some of that spirit. While science is often seen as structured and methodical I want to make science extremely creative and disruptive, and that's exactly what I've been doing throughout my profession.

I moved to Pennsylvania for college and started out on the premed track. At first, research was just something I did to check a box on my med school application. But in the summer before I applied, I went through a difficult personal time and started to question everything and see life through a radically different lens. I remember sitting in front of my laptop with my applications ready to go, staring at the price tag to submit them—over a thousand dollars. I had the MCAT score, the letters of recommendation, everything. But I paused and asked myself, “Do I really want this?”

The answer was no. I closed the laptop.

That decision created a void. I was a rising senior and president of the healthcare honor society at Penn State. I had always been a planner. Suddenly, the plan was gone. I decided to take a gap year after graduation and continue doing research. Then one day in November, sitting in a molecular genetics lecture, the professor was explaining how to clone DNA fragments. Something clicked. I remember thinking, “I really love this.” Right then and there, I decided to apply to PhD programs.

I knew I wanted to aim high—Harvard, MIT, Yale. But when I checked the deadlines, I saw all the applications were due the next day. (Yes, that’s right: the next day!)

I stood up in the middle of class and walked out. I found my research mentor and asked if she could revise my letters of recommendation so they would apply to PhD programs, not med schools. She and my teaching mentor got to work that night. I rewrote my essay, called the schools, and asked if I could submit the GRE later. Most said no. But when I called Jason Millberg, the chemical biology PhD program coordinator at Harvard, he said yes.

He still jokes that he thought I was a prank call. But I took the GRE in Puerto Rico that December, submitted my scores, interviewed, and was accepted. That’s how I ended up here at Harvard Griffin GSAS.

The Power of Clarity

Before Harvard, I thought being convincing meant using technical language. But in my teaching—and in conversations with my family and friends, who aren’t scientists—I learned that using complex terms often makes ideas harder to understand.

Now, I try to meet people where they are. I explain my work using metaphors they can relate to—machines, factories, societies. Instead of saying “post-translational modification,” I describe the protein as a product on an assembly line that gets customized along the way. I’ve learned that empathy and clarity are more powerful than jargon and thus the path to bridging science and humanity.

As a research mentor and undergraduate teaching fellow myself now, I remind my students that failure is a critical part of learning. It’s not always easy to step back and let someone struggle. But I think about what Sheila—and life itself—taught me: that sometimes the hardest choices are the ones that lead to the best outcomes.

José Del Río Pantoja’s PhD research was funded by an NIH F31 grant (National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant Number 5F31GM143896-03).

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast