Of Attention and the Great Apes

The ways that dominance shapes who gets recognized—and who doesn't—among primates

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

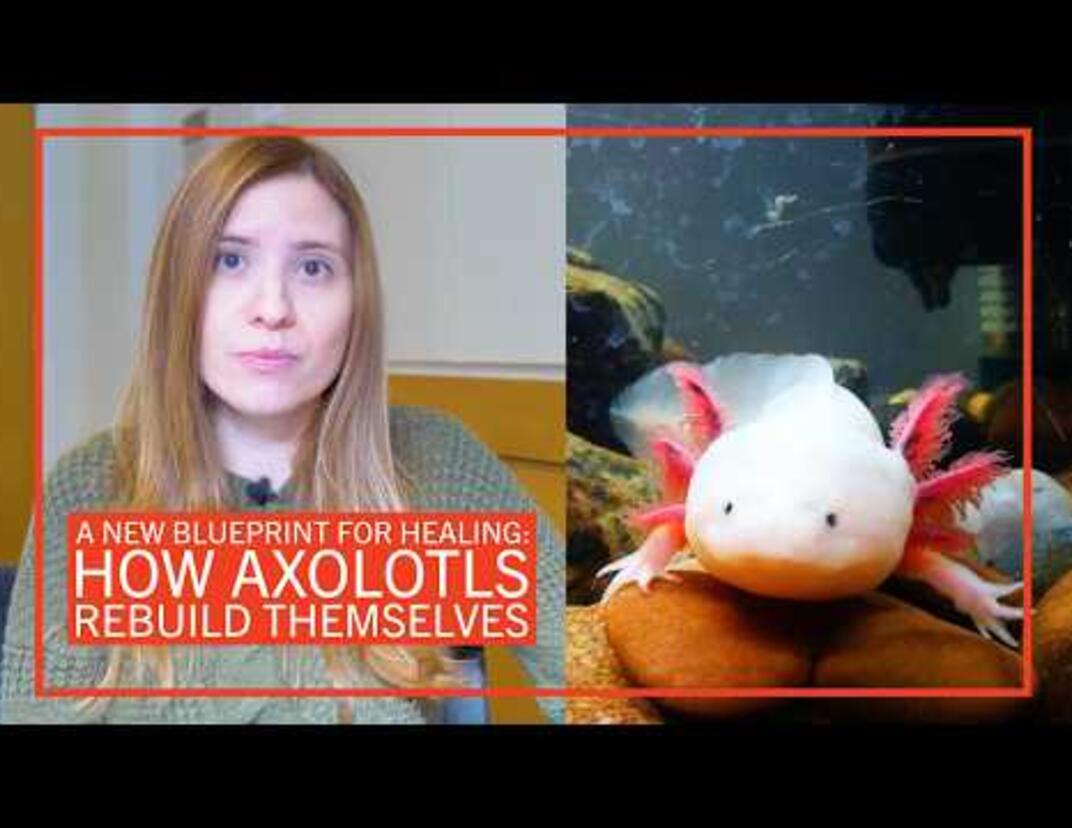

Laura Lewis, who received her PhD in human evolutionary biology from Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) last May, says we can learn a lot about our own behavior by studying the cognition of primates, particularly the way they pay attention to others.

“We know that attention in humans is also driven by dominance and prestige, just like in nonhuman great apes,” Lewis says. “This has really interesting implications for how we think about who we are paying attention to in our environment, who we are giving the biggest platforms to.”

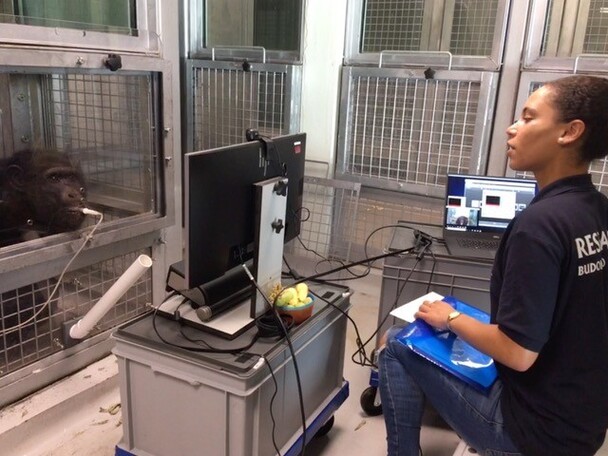

Lewis works with chimpanzees and bonobos in zoos and sanctuaries worldwide to study how they interact with their social environments. By tracking eye movement—an innovative and non-invasive method of study—she explores the ways in which primates attend to one another.

Amazing Brains

Lewis has always been fascinated by animals. As a child growing up near Berkeley, California, she was curious about the coyotes, lizards, and many other types of fauna that inhabited the ranch land that surrounded her home.

“I had this early wonder about animals and the natural world,” she says. “It inspired me to conduct science experiments in school, like testing cat food preferences and seeing whether you could teach an old dog new tricks.”

While an undergraduate at Duke University, Lewis worked at the Duke Lemur Center and the North Carolina Zoo, which fostered her desire to study primates and the evolution of social cognition.

“I fell in love with chimps as soon as I started working with them,” she says. “I’m fascinated by great apes. I want to understand how humans got from their last common ancestor—with chimps and bonobos that lived around six million years ago—to where we are now. How did patterns of evolution shape our amazing brains, which can process massive amounts of information about our social environment?”

Lewis says she decided to come to GSAS to pursue her research on primates because Harvard’s Department of Human Evolutionary Biology was home to faculty from diverse backgrounds studying the question of how humans have evolved to be the way they are today.

“It was the perfect platform,” she says. “The department had plenty of resources to help explore and expand my research to include multiple populations of chimpanzees and bonobos living around the world.”

What we found is that the dominance of sexes really affects attention patterns in these species.

-Laura Lewis, PhD ’22

Attention, Dominance, and Sex

Lewis works with primates by showing them pictures on a screen. While they look, an infrared camera tracks the animals’ eye movements, allowing her to measure the different aspects of their attention—what they look at, how long they look, and whether they pay attention to pictures of certain individuals more than others. “It’s not harmful to the animals at all,” she says. “They probably don’t even know they’re being tracked by the infrared camera.”

Because participation is voluntary, it can take hours before an individual chimpanzee or bonobo will sit quietly in front of the eye-tracking setup so Lewis can run an experiment. “We just have to wait until the animals are done with their social interactions before we can start the experiment,” she says. “We have to be very patient.”

Despite the hurdles, Lewis has uncovered a wealth of information using eye-tracking to explore social attention. During one experiment, for example, she discovered that dominance has an important influence on whether the animals pay more attention to groupmates or strangers.

“What we found is that the dominance of sexes really affects attention patterns in these species,” Lewis says. “For example, chimpanzees are male-dominant, and bonobos are female-dominant. Chimps paid more attention to their male groupmates than male strangers and didn’t differentiate as much between female groupmates and strangers. Bonobos, on the other hand, paid more attention to their female groupmates over strangers and didn’t differentiate as much between groupmates and strangers of the subordinate male sex.”

Lewis also studied the animals’ memory for groupmates that die or leave the group. “We showed them pictures of their former groupmates next to pictures of strangers to see who they would pay more attention to,” Lewis says. “They paid significantly more attention to pictures of a former groupmate, even when he or she had died or left the group up to ten years ago. We also found that both chimpanzees and bonobos looked longer at previous groupmates with whom they had more positive social interactions.”

Lewis says that her findings tell us something about human patterns of attention as well—for instance, why we may pay more attention to people who display dominance or have prestige—and what we can do to ensure that everyone is seen.

“It may be that these individuals have more knowledge and social information that we can learn from,” she says. “In Western societies, men still largely hold the majority of positions of power, and thus our attention may be more skewed toward these individuals. By allocating more prestige and positions of power to women, we as a society can help level this playing field by balancing out who we are paying attention to.”

Important Differences

Now that she’s graduated from Harvard, Lewis will advance her research by using eye-tracking methods with chimpanzees and bonobos in wildlife sanctuaries in Africa as a President’s Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley. She looks forward to working with animals in the sanctuaries, who are not typically born in captivity. “The apes are usually rescued either from the exotic pet trade or the bushmeat trade, or they were orphaned because of these industries,” Lewis says.

By providing more of a voice and a wider platform to populations who have not historically held positions of power, we can diversify who holds prestige in our society and thus to whom we are giving the most attention.

-Laura Lewis, PhD ’22

Although she believes we have a lot to learn about ourselves from the study of nonhuman great apes, Lewis says that there are important differences. A passionate supporter of transgender rights, she says she wants her work not to reinforce restrictive notions of gender and dominance, but to help us understand the importance of including more diverse perspectives that exist throughout the range of identities.

“As biological sex and gender are both on a spectrum in humans, it is important to remember that patterns of attention are likely much more complex in humans as compared to nonhuman great apes,” she says. “By providing more of a voice and a wider platform to populations who have not historically held positions of power, we can diversify who holds prestige in our society and thus to whom we are giving the most attention.”

Photos courtesy of Laura Lewis

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast