The Ascent of Chinese Education

Author Interview: William Kirby, PhD ’81

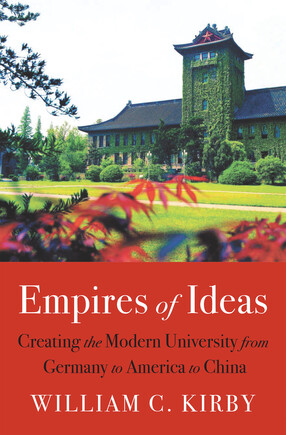

Will Chinese universities threaten the global preeminence of those in the United States? In his new book, Empires of Ideas: Creating the Modern University from Germany to America to China, William Kirby, PhD ’81, Harvard’s T. M. Chang Professor of China Studies and Spangler Family Professor of Business Administration, turns to history for answers. Looking at the trajectory of German universities, the world’s best until they were supplanted by those in the United States, Kirby says that China’s internationalism and passion for higher education could similarly propel its schools past great American institutions—including Harvard.

You’ve been a China scholar for most of your academic career. How does this new book on the future of global higher education follow from that work?

My research has largely centered on the study of China, specifically China’s return to a position of global power and the importance of internationalization in its ascent.

Chinese history is inextricably bound up with global economic, cultural, intellectual, technological, and political systems. I remember being told by an elder scholar at the Central Party School of the Chinese Communist Party, “You Westerners don’t understand China.” I said to him, “Thank you for this education because I had always thought that Marx was German and Lenin was Russian, but now I know they were actually Chinese!”

Along those lines, China’s rise should be top of mind for anyone thinking about the future of higher education. German universities, specifically the University of Berlin—today’s Humboldt University— were the models for all modern research universities, including Harvard. Eight of the top 10 universities in the world as late as the 1920s were German. Now, it’s rare that any German university cracks the top 50 worldwide. This is the crux of Empires of Ideas, which traces the modern university from Germany to America to China and poses the question that, if German universities defined the research university in the 19th century, and if American universities, without question, did so in the 20th, what are the prospects now of Chinese universities setting global standards?

One of my conclusions is that American educators have much to be proud of and a lot to worry about, especially because of the serial defunding of public higher education and public universities. Another area of concern is that American universities, despite having grown eminent by importing international ideas and scholars, no longer look abroad for new ideas. Isolation is the opposite of what makes great scholarship; it is a death sentence for higher education.

You make the case for the centrality of internationalism in China’s ascent over the past 50 years. How does that play out in the country’s higher education system?

The dust jacket of Empires of Ideas has a picture of a lovely ivy-covered campus building in China. It has a big red star at the top now because it’s under the Communist Party, but it was founded as a missionary college in 1919. It was designed by an American architect building in a Chinese style for a Chinese American cooperative project called the University of Nanking. Intellectually and architecturally, every Chinese university is international in origin and orientation.

[Chinese President] Xi Jinping has talked about how Chinese universities should not compare themselves to the rest of the world but should be their own great exemplars, and he’s encouraged some universities to withdraw from global rankings. At the end of the day, though, these schools have grown up like other Chinese institutions—business and otherwise. They have matured in an international environment. It is the great universities of Europe and North America from which they have learned and with which they now cooperate and compete. This is the company that they wish to keep and the company that they wish to lead.

The one thing that US politicians on the right and left seem to agree on is that China's rise is a threat to American primacy. How do you make sense of the increase in hostility?

I think the attitude of political leadership in both countries does a lot to shape public opinion. After Nixon went to China, for instance, there was a great wave of what I would call “sinophilia” in this country. Everything China did was wonderful and interesting, particularly compared to the Soviet Union. China was our new friend—and it had been our old friend during World War II against Japan. And yet the China that people admired in the 1970s was one hundred times more repressive, massively more poor, with a truly totalitarian political system compared to the China with which we work today—and in which so many American companies are invested and, indeed, make money.

In an editorial for The Wire China magazine, I wrote: “The United States and China each privilege self-interest over common concerns. Mutual paranoia has taken precedence over mutual benefit. Each country imagines a future of greater ‘self-sufficiency’ even if neither has ever gained from it.” There is xenophobia in both countries, but in the United States, we’re in a little bit of a new red scare with racialist tones in which the Chinese—even Chinese American citizens—are often seen as disloyal or not to be trusted.

What are your concerns about this trend? What might the impact be on higher education—specifically a place like GSAS?

The rise in tensions has potentially very bad consequences for Harvard and all the great universities in the United States. All have benefited extraordinarily over the decades from waves of Chinese students coming to our shores into our universities: in the 1950s fleeing the communists, after the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989, and then increasingly in our graduate schools today.

China is home to more of the best human capital in the world than any other country. It has extraordinary school systems and extraordinary universities. Harvard’s graduate schools have been the beneficiary of this talent—GSAS in particular because the School is entirely meritocratic. We choose our students because they’re the best in their field, and they’re chosen by the faculty, not by a central admissions committee. When we cease to have the capacity to bring the best and the brightest to a place like the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, then we will decline. There’s no doubt about it.

History shows that a self-isolating China is a danger to itself and a loss to the world. The same may be said about the United States.

Photo Courtesy The Harvard Center, Shanghai

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast