Aging Poetically

What three nonagenarian Slavic-language women writers reveal about the creative potential within the experience of aging

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

While attending a Catholic high school affiliated with the Society of the Sacred Heart, Alex Braslavsky spent time with a retirement-age community of nuns living on campus. She developed a close personal and writerly friendship with one member of the group, Sister Carol Duchesne Bialock, who was an active poet and educator in addition to her religious work. The two met each week, wrote, and talked about poems they’d created and read. Sister Bialock also shared her worries about getting older. “I remember her saying that her biggest fears were to lose her memory and to not be able to read anymore,” Braslavsky says.

Sister Bialock died in 2020. Her poetry, a large body of work, was collected in a book that included many she had read to Braslavsky. “That experience, as well as others before, has always been in the back of my mind as I consider my work,” Braslavsky says. “I want to write about women who wrote poetry for a very long time, who aged with their poems, and whose poems aged with them.”

As a PhD candidate in Slavic Languages & Literatures at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS), Alex Braslavsky explores the ways art and poetry can provide unique and powerful insights into how humanity responds to old age––and to all stages of life. Her 2025 Harvard Horizons project, “Embracing Twilight: Older Women Poets and the Unfurling of Their Voices,” focuses on three women poets writing in Slavic languages, whose later works reveal the experience of aging to be a source of creative possibility. As lifespans increase around the globe, Braslavsky’s work shows how old age can be a time of new vitality—and how art can be a place for spiritual reckoning in old age.

Aging With Agency

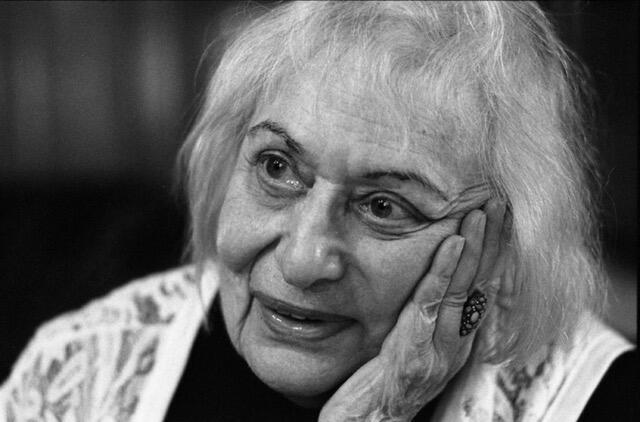

Braslavsky’s project draws on her current dissertation research. Through a comparative study of poets writing in three different Slavic languages—Krystyna Miłobędzka (b. 1932) in Polish, Bohumila Grögerová (1921–2014) in Czech, and Elizabeta Mnatsakanova (1922–2019) in Russian––Braslavsky reveals the experience of aging to be a source of inspiration in their works, many of which feature experimental, avant-garde elements. She also hopes to challenge mainstream ideas of weakness and decline in old age, instead emphasizing these poets’ creative decision-making in response to the conditions of advanced age.

By studying these three innovative poets together as a trio, Braslavsky aims to highlight how they treat the experiences of aging as motivation for developments in their artistic work. As Harvard Professor Stephanie Sandler, one of Braslavsky’s dissertation advisors and the Ernest E. Monrad Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures, explains, “The poets she has chosen combine formal difficulty, curiosity about all of life’s stages––from childhood to old age––and multiple innovative practices.” Accordingly, explains Braslavsky, “these women are making decisions, and there is an agency that accompanies their aging, rather than the stereotype of decline that we often succumb to when discussing artists in older age.”

In Miłobędzka’s case, the need to question the reliability of her own memory enabled the development of a new style of poetic narration in which the poet wrote with an ambiguous sense of personal identity and also honed in on the intricacies of the present moment. “Miłobędzka reaches for a self beyond the self in her later poetry,” Braslavsky says. “The self is very confluent with natural surroundings, and it fuses and melds with natural emblems, trees, and the sky in her late work. Miłobędzka also uses language more and more sparingly as she ages, cutting out extraneous bits of language and abiding by her belief in the resonance of the ineffable. She, in effect, reaches towards a language beyond language.”

Likewise, the experience of age-related visual impairments became a source of powerful poetic influence for the Czech poet Bohumila Grögerová, who began losing her eyesight in her eighties. “Previously she had written concrete poetry, where the spatial arrangement of the typeface text on the page creates a visual image that resonates with the poem’s topic,” explains Braslavsky, “so the shape of the text really mattered to her on the page. That poetry was very visual.”

These women are making decisions, and there is an agency that accompanies their aging, rather than the stereotype of decline that we often succumb to when discussing artists in older age.

—Alex Braslavsky

Focusing on a collection of Grögerová’s poetry written while her vision was declining, Braslavsky has observed how vision loss inspired an aesthetic shift for the writer. “Instead of concrete and visual poetry, she ended up writing about the warpings and discolorations in her sight, and claiming those as images in their own right in her work,” Braslavsky explains. “She began to formulate a new kind of vision––and then that turned into a sort of inner vision, giving her late work a new quality. So, the visual was still important to her in her late work. It just transmogrified, and she began expressing visual images differently.”

The idea of stylistic development is closely linked to that of aging, Braslavsky explains, because both processes unfold over large spans of an artist’s lifetime. The Russian poet Elizabeta Mnatsakanova, Braslavsky notes, is remarkable for how she aged in time with some of her artistic works, creating multimedia “albums” comprising poetry, photography, calligraphy, and watercolor painting that she continuously produced and revised over the course of multiple decades.

“One text I’m studying is called The Book of Childhood,” Braslavsky says. “There are several manuscripts of this text, and she continued to rewrite or radically revise this text. The first version is dated to 1973, and she revised it until 2018––so, that’s about five decades of work on one manuscript poetic sequence.”

Mnatsakanova’s manuscripts, held at Harvard’s Houghton Library, reveal developments in her aesthetic and techniques over the years, which Braslavsky sees as crucial traces of the evolution of the poet’s artistic voice as she grew older and, with age and time, learned to take risks within the styles and methods she had developed.

“I argue that the versions of The Book of Childhood are all one work, radically revised again and again and again, and there is no single final version,” Braslavsky explains. “And what’s important about that is that Mnatsakanova grew in her experimentation over the years. There’s a sense of her experiencing liberation in her art, which is brought about solely because of this longstanding foundation, and the long-term experience of the personal predicaments of her art forms.” In other words, the experiences of both personal and artistic growth over time were intimately linked in Mnatsakanova’s work, revealing how the perspective and depth of experience offered by age can enable new expressive possibilities.

Expanding Slavic Studies––and the Philosophy of Artistic Style

The poets Braslavsky studies reveal that artworks representing all life stages make powerful statements worth appreciating––about their artists and about the human experience. This idea stands in contrast with the typical notion that an artist, honing their craft over time, follows a direct path towards a “mature” stage when they create their best work. Harvard Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures Aleksandra Kremer, who is also one of Braslavsky’s dissertation advisors, notes, “Within the humanities, the poets Alex has chosen to study complicate and supplement what better-known thinkers and theorists (such as Adorno, Said, de Beauvoir, Sontag, and others) have said about aging and late style in literature and arts.”

In addition, Braslavsky’s perspective on these issues is informed by her own experience as a literary translator. “In my work as a translator of poetry, I have found that there's an expectation to curate the masterworks––like in an edition of selected poems––and to not showcase any vulnerability on the part of the poet, only the best pieces,” she reflects, “and I take issue with that because, in that case, we can't see the development of how the poet got to where they were trying to go, and what the germinating aspects of their creative processes were as they aged.”

[Alex’s] commitment to multiple Slavic languages is deep, and she sees herself as part of a generation of scholars who are diversifying the field of Slavic studies, a welcome trend.

—Professor Stephanie Sandler

Finally, in addition to considering issues like age, gender, and ability, Braslavsky hopes to expand methods in the academic field of Slavic studies by adopting a comparative approach, considering works across multiple Slavic languages. Doing so has required sustained, intense language study. As Prof. Sandler says of Braslavsky, “Her commitment to multiple Slavic languages is deep, and she sees herself as part of a generation of scholars who are diversifying the field of Slavic studies, a welcome trend.”

Intergenerational Friendships

Braslavsky’s research interests take inspiration from her own experiences connecting to members of older generations like Sister Bialock. Her choice to pursue Slavic languages specifically stems from Russian familial roots, and she began learning the Russian language through visits with her grandmothers in Moscow. “In college, I saw my grandmothers every summer––at a time when it was possible to go to Moscow safely––and I would go back and forth between their two apartments, speaking Russian with them, while they would playfully compete as to who was the better grandma, and who cooked the best dishes,” she recalls.

In addition, Braslavsky says, this language learning experience itself connects to her interest in studying age: the challenges of expressing herself with limited vocabulary in the earlier days of learning Russian brought her back to what felt like a childlike state, while her grandmothers’ old age made it urgently important to learn to communicate with them. “It was very formative for me to really be mothered through language again,” reflects Braslavsky, “and I also felt that time was pressing. Since these were my grandmothers, I knew they wouldn’t be around forever. Then, in my senior year of college, because I had studied Russian, I began to write a thesis on Russian poetry, and that was an important beginning for my academic research.”

The challenges of age are eternal issues we’ve been grappling with for a long time. The arts are incredibly important as we try to make sense of why we’re on this Earth, and to comprehend things beyond understanding.

—Alex Braslavsky

However, Braslavsky’s beginnings as a writer and poet extend earlier into her childhood––and, again, were markedly impacted by connections to older generations. “Some of the most formative experiences that made me a writer had to do with intergenerational friendships,” Braslavsky says. As a seven-year-old, Braslavsky remembers, she began writing regular letters to an elderly woman, known to her as Mrs. Morello, and their written exchange continued for four years. Braslavsky was put in contact with Morello by one of her parents, who worked as a handywoman and had made repairs in Morello’s home. “I never once met Mrs. Morello, but I wrote her countless letters,” Braslavsky recalls, “and it was important that I was writing to someone, who was encouraging me to write.”

Through her research on poetry and artmaking throughout life’s various stages, Braslavsky hopes to change how we think about old age by shedding new light on the creative potential bound up within the experience of aging. “The reality of our aging global population is obviously an interdisciplinary discussion,” Braslavsky says, “and I want to speak with people across disciplinary divides. The challenges of age are eternal issues we’ve been grappling with for a long time. The arts are incredibly important as we try to make sense of why we’re on this Earth, and to comprehend things beyond understanding. And poetry is something that can accompany you throughout life.”

Don't miss this year's Harvard Horizons Symposium in Sanders Theatre on Tuesday, April 8, 2025. Free and open to the public.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast