Accessing the Mother Lode of Renaissance Drawings

How a connection between Harvard’s faculty of arts and sciences and the Uffizi gallery helps graduate students make great discoveries.

In the 16th century, Pope Paul III commissioned the Italian architects Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Jacopo Meleghino to build him a citadel atop a hill in Perugia, a city in central Italy. Paul III requested that medieval touches be added—such as battlements and old-fashioned slits for artillery—that served more as symbols of papal dominance over the population than as strictly utilitarian features, at a time when such elements were increasingly obsolete in warfare. In essence, the pope had requested retro architecture.

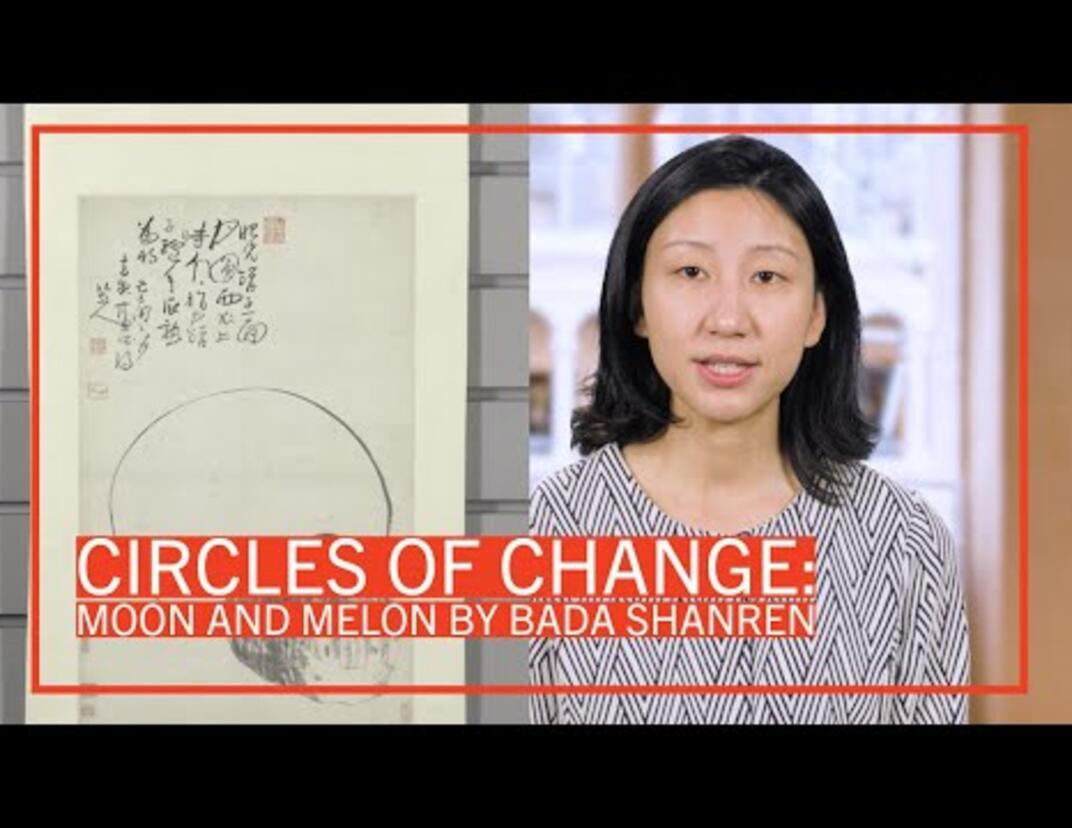

The meaning of these unusual ornamentations lay hidden in Sangallo’s drawings for the commission deep in the vaults of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That is until last year when Morgan Ng, a PhD student in architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning, began an internship at the museum.

“My project was to study a large body of drawings for an important 16th-century papal fortress, known as the Rocca Paolina, with two objectives,” Ng explains. “First, to complete an in-depth museological study—transcribing all the annotations on the drawings, documenting their various mediums, states of conservation, and including an up-to-date bibliography—and to input all this information online. Second, I conducted original research—studying archival records to reconstruct the drawings’ provenance—with the goal of synthesizing the latest findings into an essay available online to scholars.”

In the process of reviewing Sangallo’s drawings—over 30 of them are included in the Uffizi collection—Ng noticed a disconnect between the architecture and the style of warfare at the time. “This was a time of artillery, so it was odd for the pope to request elements that appeared as though they were designed to allow soldiers to pour boiling oil onto attackers or let loose their arrows,” he explains. “These architectural touches, I concluded, revealed that the pope was thinking about fortress design in psychological terms. This Renaissance pope deliberately chose medieval features over cutting-edge technology, because he knew his subjects would immediately recognize them as symbols of political control.”

Ng’s involvement at the museum—and his discovery—came about thanks to a relationship developed between his dissertation advisor Alina Payne, the Alexander P. Misheff Professor of History of Art and Architecture, and Marzia Faietti, director of the Uffizi Department of Prints and Drawings. “As a scholar of Italian Renaissance art and architecture, I have spent a great deal of time in Florence and collaborated with Marzia Faietti on several projects,” Payne says. “I proposed the internship because not only would the museum gain intelligent, motivated students to help inventory its collection but it would also provide an extraordinary opportunity for our students to engage with primary materials in a world-class museum.” Since its establishment more than three years ago, the internship has sent five Harvard graduate students to Florence to assist with the Euploos Project, an interdisciplinary program at the museum’s Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi.

The Euploos Project is dedicated to making available on the Internet a complete computerized catalog of its collection, more than 150,000 works—drawings, prints, miniatures, and photographs—dating from the 14th century to the present. Student interns study the objects directly, guided by project supervisors. They publish their results and develop virtual exhibitions, all of which are incorporated into the Euploos Project website.

The program has received the full support of Harvard’s administration. “This is a valuable internship that allows graduate students in the history of art and architecture to avail themselves of the extraordinary collections in the Uffizi,” says Diana Sorensen, dean of arts and humanities. “We are grateful to Professor Alina Payne and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences for making this opportunity available to our students.”

Because the Uffizi holds so many uncataloged drawings, each student is able to look at materials related to their research. “Faietti and I discuss what our students are interested in, and she collects drawings that will help them move their dissertations forward,” explains Payne. “Since Morgan works on fortifications and military architecture of the Renaissance, he examined sketches related to that.” After intense investigation, Ng created physical descriptions and determined provenance for each piece. He then surveyed the literature to discern where the sketch fit into the architect’s career. “It is very important for students who will be active in this field to understand the materials and the objects themselves,” says Payne. “What type of paper is it, what watermark exists, what kind of ink or pencil was used.” Based on his results, Ng drafted substantial entries that will soon appear on the Euploos Project’s website.

Ng found the internship to be a wonderful way to advance his dissertation, which concerns how the 16th-century culture of stealth, surveillance and deception in warfare came to influence the design of military architecture and, later on, the spatial configuration of palace complexes. “This collection is the mother lode of Renaissance drawings,” he says. “The rare chance to study over an extended period these important and fragile visual documents has provided the nucleus for one of my dissertation chapters.” He also learned how to conduct technical analyses of such documents—studying watermarks and mediums as clues for dating, reading, transcribing, and distinguishing 16th-century handwriting and understanding how such sheets are altered over time. “My knowledge in this area has since paid great dividends in all my subsequent documentary research,” Ng shares. “Every time I discover a new drawing in another archive or library, I am now equipped to do technical analyses of the sort I learned to at the Gabinetto.”

Victoria Addona studies Renaissance architecture as a doctoral student in the history of art and architecture, focusing on intersections between architecture and painting, and the development of art theory in granducal Florence. She had the opportunity to work with Faietti and the Gabinetto’s vice-director, Giorgio Marini, over two summers during coursework. “During my first year, I compiled extensive bibliographies for the first ten plans of the new St. Peter’s,” Addona says. “My second summer built off that experience and involved the consultation of drawings that form the basis of my dissertation topic.” She cataloged approximately 30 pieces by the Florentine architect and set-designer Bernardo Buontalenti, completing entries on three of his major projects: the Porta delle Suppliche, the façade of the Casino Mediceo, and the façade of the Palazzo Nonfinito.

“Before my internship, I was unfamiliar with the technical study of architectural drawings, a genre that is now a primary focus in my dissertation,” Addona explains. “The Gabinetto’s collection of Renaissance Italian architectural drawings is unmatched in Europe, and close study of its material in the context of a rigorous internship helped form a skillset that will be crucial to the development of my future research.” Her onsite exposure to Florentine architecture and the many art historical institutions and resources in the city had the added benefit of shaping possible dissertation ideas at an early stage in her graduate career.

Like Ng, Addona found the internship transformative. “I hope to continue working in academia, teaching and researching architectural history,” she says. “The Uffizi internship provided a key opportunity to become acquainted with museological practices and issues, and specifically, the strong collection of a crucial research institution within my subfield and a broader European network of art historical practitioners.”

Ng’s Uffizi internship experience influenced his plans for the future. “I hope to continue research as a college or university professor, either in an art history department or in an architecture program,” he says. “Research never ends, of course, and the kind of knowledge I acquired at the Gabinetto will continue to serve me when I work on new documents. More generally, I learned the value of patiently studying these material artifacts, and to look closely at drawings for clues into the thought processes of their artists.”

This attempt to gain a glimpse into the mind of a particular architect or artist can seem a bit like traveling back in time. On a visit to the Uffizi late last spring, Payne met with Faietti and two graduate students to review drawings of the Pantheon attributed to Raphael. “We spent hours analyzing them, turning them over to determine which lines were drawn first and which at a later time, arguing about what we saw,” recalls Payne. “In the end, we concluded that there were more hands at work, not just Raphael’s but one of his students as well.” The excitement of this discovery, and the collaboration that led to it, forms an unforgettable experience for GSAS students. With direct access to some of the most famous drawings in the world, they are able to peer into the past and determine what an artist was thinking at the moment he picked up a piece of paper to draw.

Photos by Ben Gebo, Gianni Trambusti

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast