Media Wars

Alexander L. Fattal, PhD ’14, examines the role of media in the decades-long military conflict between the Colombian state and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)

In Guerilla Marketing: Counterinsurgency and Capitalism in Colombia, Alexander L. Fattal, PhD ’14, assistant professor at UC San Diego, examines the role of media in the decades-long military conflict between the Colombian state and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Fattal’s ethnographic analysis of the Colombian Ministry of Defense’s demobilization program reveals how slick ad campaigns “weaponized advertising” as a means of persuading leftist fighters to demobilize and inform on guerrilla operations. As the Colombian government rebranded counterinsurgency as a humanitarian effort to rescue guerrilla combatants, the military conflict between the state and the FARC also became a “brand war.” Fattal shows how techniques of consumer advertising became part of an arsenal of counterinsurgency tactics for the Colombian government and a form of expertise to be exported around the world.

What drew you to Colombia?

As an undergraduate at Duke University, I spent a semester abroad in Chile, and I had studied Spanish since high school. At Duke, I was influenced by the Center for Documentary Studies and wrote a thesis on the role of photography in the South African liberation struggle. I was very interested both in the politics of the image and in Latin America. I put together a proposal for a Fulbright in Colombia with no expectation that I would get it. Lo and behold, I get the grant and started teaching photography to kids in Bogotá, many of whom had been displaced by the armed conflict in 2001. That project became Shooting Cameras for Peace, which ran as a nonprofit between 2001 and 2009.

There’s a scene in the book where you’re in the library questioning the need for another study of Colombia. But you write that fieldwork changed your mind.

I was in Harvard’s Widener Library among rows and rows of books on the Colombia conflict—a conflict that in many ways has been over-diagnosed going back at least to the 1950s. What was my marginal contribution going to be? Then I realized there was a lack of work that takes seriously the role of media representation. For me, the media is not an ancillary dimension of the conflict, but rather fuels it by providing a discursive frame that allows it to continue. When I got access to the Colombian Ministry of Defense’s Program for Humanitarian Attention to the Demobilized, there was something very pointed about discovering the dynamics of information warfare. In the field I could see there was something to the inkling I had when I was wandering the stacks.

What makes Colombia such rich ground for the synthesis of marketing and militarism?

For starters, extraordinarily close geopolitical connections to the United States. It’s a historical relationship—Colombia sent frigates to South Korea to fight beside the US in the Korean War. But when the decision was made in the late 1990s to step that up, it wasn’t only with Black Hawk helicopters, but also with a parade of advisors specializing in black ops and the fusion of propaganda and military intelligence. In 2007, the RAND Corporation published a report, Enlisting Madison Avenue, as the US was clearly flailing in Iraq and Afghanistan. The thinking was, “well we need to do some concerted learning from the advertising world” as a way of dealing with insurgency. This grafts onto what historian Greg Grandin calls “empire’s workshop”—the idea that Latin America serves as a testing ground for American military tactics and strategies. If you look at the trajectory of some recent US ambassadors, they return to Washington, DC, from Colombia and then head off to Kabul. There’s a general sense that lessons gleaned from the Colombian counterinsurgency can be applied in the Middle East. It’s the combination of an experimental yet deeply conservative, market-oriented context that makes Colombia so interesting.

The book has a very elegant structure, with your ethnographic analysis of media and advertising campaigns interwoven with testimonies from demobilized guerillas. How did you arrive at that structure?

I wanted to be careful not to give the impression that the conflict could be reduced to media representations. The testimonials do important work in fleshing out the dynamics of the conflict: why people join the guerrillas so young; the depressed economy in many rural areas; income inequality; the kind of push factors that drive people to join the FARC and the National Liberation Army (ELN). I wanted the book to be layered—that’s what anthropology does so well.

Your book reads as if it were written by someone who has read George Orwell on politics, David Ogilvy on advertising, and Marshall McCluhan on media. Who are some of your influences?

Orwell is definitely an interest: In Homage to Catalonia, he writes about the propaganda of soldiers shouting across the trenches about what they’re eating at Christmas time. Under the sheen of the marketing campaigns, a basic message can often be reduced to “You’re hungry. We’re not hungry.” But the way Orwell describes it, his prose is just extraordinary, it’s direct.

I also love Jon Lee Anderson’s reporting and his dispatches from Latin America for The New Yorker.

What’s next?

I’m about to premier a short film. Limbo is drawn from one of eight interviews I did with former guerillas in a truck I turned into a camera obscura. This dark space of the camera obscura becomes a confessional chamber, a kind of psychoanalytic space for the former guerrillas.

The film profiles one guerrilla fighter, also named Alex. He has this recurring dream in which the devil is trying to take him away, and he challenges the devil to a duel. He’s wrestling with his own conscience for “working with a pistol.” It’s only upon taking yagé that he excises his dreams. What comes across in the film is a life stuck between a military past and a civilian present, between being a victim of all sorts of structural problems and also clearly being a perpetrator as well.

My other major project is a bilingual photography book, Shooting Cameras for Peace: Youth, Photography, and the Colombian Armed Conflict, to be published by the Peabody Museum Press. It examines the archive of photographs taken by the young people who photographed their lives in Los Altos de Cazucá, southwest of Bogotá.

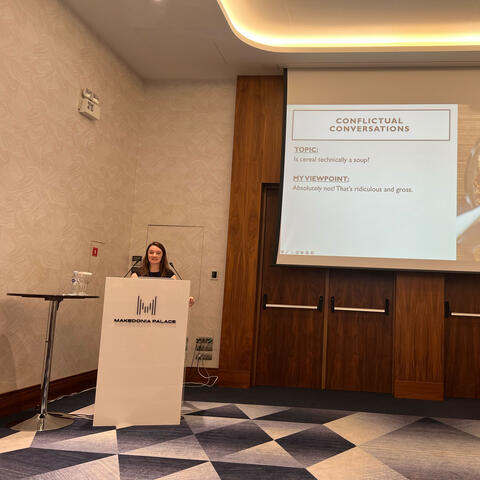

Watch Alexander Fattal speak at Harvard Horizons 2013:

Photo by Ben Gebo

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast