A Long, Strange Trip

LSD’s path from miracle drug to social menace

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

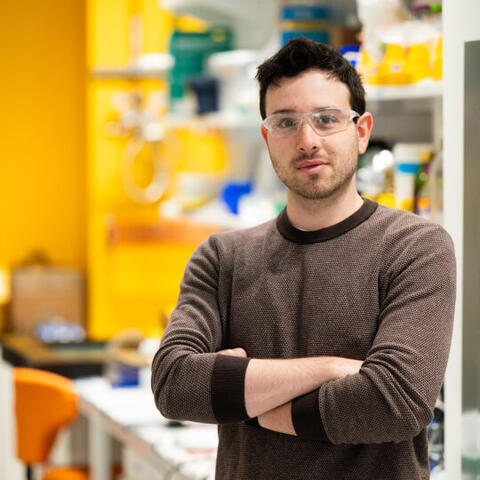

For Alexis Turner, the story of lysergic acid diethylamide’s (LSD) changing place in the culture of the United States is almost as colorful, eclectic, and disturbing as the visions that the psychedelic drug induces in its users.

“At different times throughout its history, LSD has been a psychiatric wonder drug, a means to world peace, a distraction from political progress, and a poison corrupting the youth of the country,” Turner says. “Intellectually, I want to know how it can be all those things—sometimes simultaneously.”

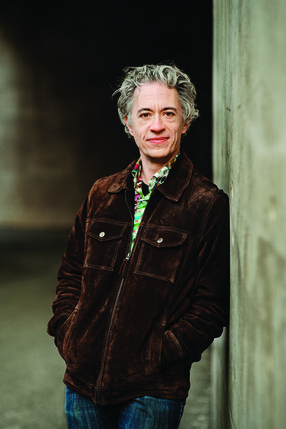

As a PhD student in the history of science at Harvard’s GSAS, Turner studies LSD as an example of how technologies get politicized—and how attitudes about them become polarized. Moreover, by exploring the psychedelic’s history from the dawn of the Cold War through the Nixon Administration, Turner not only sheds light on who used LSD, who opposed it, and why, but also on the ways that race and class shape the nation’s policies on drugs.

Searching for the Manchurian Candidate

Albert Hofmann, a chemist for the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Sandoz, first synthesized LSD in 1936. The drug didn’t make it to the United States until the late 1940s, however, after researchers began to consider its potential to advance the study of psychotic states. Almost immediately, LSD became the object of intense study. Research proliferated so rapidly that, by the early 1960s, Sandoz discontinued its annual bibliography of papers published on the drug because their number had risen into the thousands. Before long, clinicians had discovered LSD as well and began using it to treat alcoholism and psychological trauma.

“For the first 20 years of its history, researchers and clinicians were excited about LSD,” Turner says. “It was being used in therapy essentially to create a waking dream state to surface and interpret the unconscious in real-time. The idea was to smash seven years of therapy into one seven-hour drug trip. Psychiatrists gave it out like candy. I think [the actor] Cary Grant had it over 100 times.”

As enthusiastic as some in the medical community were about LSD, Turner says that no researcher, clinician, or organization was more interested in the drug than the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Referencing the 1975 report of the Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (the Church Committee), Turner says that the CIA was interested in psychological manipulation rather than expanded consciousness.

For the first 20 years of its history, researchers and clinicians were excited about LSD … Psychiatrists gave it out like candy. I think [the actor] Cary Grant had it over 100 times.

“Brainwashing was a big question at the time during the Cold War,” he says. “Think of the movie The Manchurian Candidate. US intelligence agencies believed that the Chinese had learned how to brainwash people, so they thought, ‘We better figure out how to brainwash people too.’ LSD was one of the drugs that they hoped might be able to do this.”

Turner says that the CIA had other hopes for LSD as well.

“They thought of using it to engineer bloodless coups,” he says. “The idea was to dose everyone in a city and incapacitate them for seven or eight hours while US or US-backed forces went in and took over. They also thought it might be useful as a truth serum because people relax and tend to become more talkative when they’re tripping. My favorite, though, is that the CIA tested subjects to see if LSD increased people’s capacity for extrasensory perception—essentially, whether it could make them psychic."

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out

By the early 1960s, LSD was transitioning from miracle drug/weapon of mass delusion to countercultural touchstone. While a couple of former Harvard psychology faculty—Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, who later assumed the name Baba Ram Dass—are often given credit for popularizing the drug with the youth culture of the era, Turner says that Oscar Janiger, a California psychiatrist who “administered almost 3,000 doses of LSD to 1,000 volunteers,” played a more direct role in its spread.

“Janiger gave the drug to more people than anyone else,” he says. “And he gave it to well-known people, famous people, creative people. Not just Cary Grant, but also the writers Anaïs Nin and Aldous Huxley; Jack Nicholson, who made movies about LSD; and Rob White, who wrote the first screenplay that explicitly mentioned LSD. He gave it to the British philosopher Alan Watts who wrote The Joyous Cosmology: Adventures in the Chemistry of Consciousness in 1965, a whole book on LSD.”

The members of the creative class—and others of means and influence who experienced LSD both in and out of treatment—raised awareness of the drug and its possibilities for expanding consciousness. Publicized by figures like Alpert and Leary—who famously encouraged Americans to "Turn on, tune in, drop out"—LSD migrated to the center of a utopian vision that was increasingly unsettling to middle-class society.

“All of these writers, actors, producers, and artists…those are the kinds of people that the counterculture learns from,” Turner says. “Then you have Leary saying, ‘If everyone just takes LSD, there will be world peace.’ Meantime, youth culture was like, ‘We’ll have sex in the streets!’ Adults thought they were going wild with it, totally out of control.”

In 1962, Congress passed the Drug Efficacy Amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, creating strict guidelines for the certification of new drugs and empowering the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to enforce them. Turner says the measure was a turning point in the history of LSD, one that solidified its move out of the medical establishment and into the counterculture.

“The 1962 law essentially created the modern clinical trial as we understand it today,” he says. A drug had to show medical promise, and it was very difficult for LSD to justify itself for continued research and development as the FDA defined that requirement. It wasn’t illegal, but it was much harder to get, which drove it underground and made it both more attractive and more available to youth culture.”

Not everyone who wanted to transform society believed that LSD was the path to revolution. Some saw it as an obstacle—a way to keep people docile and submissive instead of militant and active. Turner tells the story of Timothy Leary’s brief relationship with the Black Panther Party. The Weather Underground (WU), a militant leftist group, broke Leary out of prison in 1970 and smuggled him and his wife to Algeria to stay with the International Section of the Black Panther Party led by Minister of Information] Eldridge Cleaver. Turner says that the episode contributed to the schism that led to the Panther’s dissolution.

“The WU wanted to create an alliance between the hippies and the radical left, but Leary was taking drugs and behaving in ways that could have gotten the Panthers kicked out of Algeria. Cleaver was outraged. He said, ‘If you think that by tuning in, turning on, and dropping out you’re improving the situation, that you’re changing society, it’s very clear that you’re doing nothing except destroying your own brains.’ He ended up putting Leary and his wife under house arrest. The FBI used the incident to exploit existing rifts in the party, which eventually led to the Panthers splitting apart.”

Lies, Coke, and Disco

The election of Richard Nixon in 1968 on a law and order platform signaled the decline of the counterculture and a ramping up of the war on drugs. LSD was one casualty. Turner says that Nixon’s campaign and then his administration tied recreational drug use to social disorder and fear of the racial other to defeat the American left. He points to the account of Nixon Administration White House Counsel John Ehrlichman in 1994:

We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the [Vietnam War] or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.

“Historically, it has been very easy to make drugs the centerpiece of a ‘tough on crime’ approach in the US,” Turner explains. “It’s deeply wrapped up in the country’s history of racist discourse. LSD users were mostly white, so the right associated it with the Beats, white poets known for hanging out with Black people. Beatniks were the ‘bad’ white people who were too close to the communities of color that threatened to infiltrate middle-class, white suburbs.”

Congress criminalized possession of LSD in 1970 when it passed the Controlled Substances Act, which categorized it as a substance with “no currently accepted medical use” and a “high potential for abuse.” Turner says the drug was also the victim of a shift in youth culture.

“When the Church Committee released their report in 1975 and revealed all the links between the CIA and LSD, that was really a death knell,” he explains. “LSD became ‘The Man’s’ drug. Then, with the rise of the disco scene, cocaine became the drug of choice going into the 1980s.”

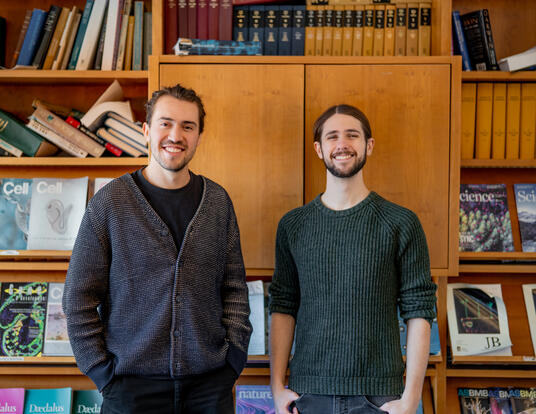

While history never repeats itself, as the saying goes, in the case of LSD it does indeed appear to rhyme. The writer Michael Pollan’s 2015 New Yorker article, “The Trip Treatment” and subsequent book, How to Change Your Mind again presented psychedelics as miracle drugs that “could revolutionize mental healthcare and our understanding of the mind.” Earlier this year, Massachusetts General Hospital launched its new Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics led by Jerrold Rosenbaum, Harvard Medical School's Stanley Cobb Professor of Psychiatry. Because of this renewed interest in the potential of LSD, Turner’s adviser, Professor of the History of Science in Residence Elizabeth Lunbeck, says that his research project is particularly timely.

I am a little concerned that some of the [efforts to rehabilitate LSD] rely on the ‘good science versus bad science’ distinction that got it into trouble in the 1960s.

“Alexis wants to use the LSD story to work through issues around science, democracy, and the public sphere that engage us as citizens: the nature of expertise, the obligations of the scientific researcher, and the racial and class politics of drugs,” she says. “At the same time, he is digging deeply into the archival evidence, finding all sorts of surprising testimony to the drug’s ubiquity and normalization in the run-up to its demonization. As LSD is being recouped for science and therapeutics proper, Turner’s decision to take on this exemplary ‘fall and rise’ story is proving prescient indeed.”

While Turner is intrigued to see LSD come out from the shadows, he worries that scientists are repeating some of the mistakes of the past.

“I am a little concerned that some of the current [efforts to rehabilitate LSD] rely on the ‘good science versus bad science’ distinction that got it into trouble in the 1960s,” he says. “That leads to medicalization and heavy regulation, which tends to create black markets because of the high prices that pharmaceutical companies charge for new drugs. And in this country, the people who often bear the brunt of criminalization are Black and Brown, queer, and poor.”

Rather than incarcerating everyone who uses LSD or consigning the drug again to the control of the medical establishment, Turner hopes policymakers will pursue a simpler solution: decriminalization.

“It’s more of an uphill battle,” he admits. “The people pursuing medicalization are pretty savvy. Their strategy takes into account the fears of the public and the misinformation around LSD. But when you consider the potential impact on social and racial justice, I believe that decriminalization is a better option in the long run. Let people purchase and use LSD safely as they choose.”

Banner courtesy of Shutterstock; Photo by Jared Leeds

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast