China in Africa: Exporting Authoritarianism?

China scholar questions conventional view of China’s “grand strategy” on the continent

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

China-Africa relations are increasingly drawing attention from leaders and policymakers around the world—and for good reason. In 2009, China became Africa’s largest trading partner. Over three dozen countries in sub-Saharan Africa are participating in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a massive global infrastructure project that has been imagined as the modern-day equivalent of the medieval Silk Road trading route. Nations such as Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya have already partnered on high-profile projects and/or purchased hundreds of millions of dollars of technology from China, which offers financing on reputedly generous terms.

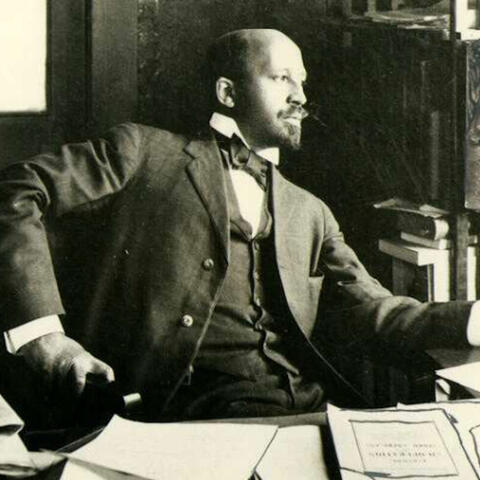

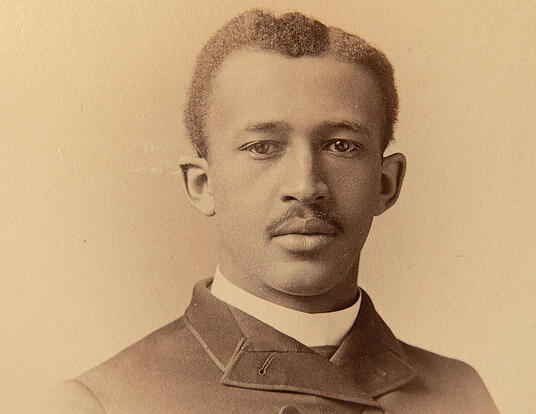

So far, however, analysts have tended to look at the relationships between China and the nations of Africa primarily through the lens of the former’s geopolitical strategy and goals. GSAS PhD candidate Bulelani Jili takes a more critical posture towards Africa-China relations. A cybersecurity fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, a futures fellow at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, and a research associate at the University of Oxford’s China, Law and Development Project, Jili explores what motivates countries on his home continent to engage with China, particularly in the realm of information and communication technology. In a recent interview with GSAS Communications, he asserts that the tendency to see China as “exporting authoritarianism” both portrays African nations as passive and fails to identify the reasons that regimes—both democratic and repressive—have for doing business with their Asian partner.

GSAS: How have scholars traditionally misportrayed the relationship between China and the nations of Africa? How is your work different?

Bulelani Jili: There’s a kind of debris of Cold War logic that assumes that Africa and the Global South are just static stages on which superpowers play. It views China’s engagements narrowly in terms of a “top-down” strategy and obfuscates the particularities of the local environments in which it operates. A racialized and colonial logic is also at work here that determines how we choose to conceptualize Africa and its people. It fragments and refracts how we see and disables our ability to think critically about African volition.

My research aims to draw attention to what’s happening on the ground in Africa as a way to examine the condition of action in relations with China. I am interested in recognizing the agency of African state actors that are generally considered either passive or just mediating instruments and also in thinking through the terms of how African actors themselves negotiate their arrangements with China. That perspective complicates not only the way we conceptualize Africa but also our sense of how China engages with the world.

It takes a lot of time for people to realize that African foreign policy matters—the same way it's very difficult for people to realize that Black lives matter. There's something quite strange about ignoring a continent.

There's something quite strange about ignoring a continent.

GSAS Communications: In a 2019 research brief you wrote for Oxford’s China, Law and Development Project, you discuss the importance of recognizing China’s “supply motivations” in its relations with Africa. What did you mean by that?

Jili: China needs a supply of natural resources to maintain its economic growth: coal, wood, and importantly oil. That was a key motivation for them in engaging with Africa—Angola in particular.

When you look at oil closely, the United States has a firm grip on oil supplies from the Middle East. China was looking for supply in an alternative arena. Africa was a key destination for that. And so, in that sense, it’s a pretty traditional economic supply relationship.

GSAS Communications: Is it that simple? Is economics the driving factor in China’s relationship with African countries?

Jili: There's another aspect, which is more diplomatic. Historically African countries have been quite supportive of China's engagement with the world, specifically at the level of intergovernmental institutions like the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. Africa’s been an important voting block for China, so maintaining those relationships diplomatically is paramount.

At the same time, Africa is trying to move away from being a site of extraction and move along the chain of economic activity to production. China, which is in the global South, has responded with a lot of rhetoric about supporting other global South partners in development initiatives—and with the exportation of infrastructure, investment, and development aid to Africa.

My research tries to understand the balance between motivations that are tied up with China’s domestic supply needs and those that respond to local conditions in Africa. In the tech sector, for instance, African actors are realizing that we’re reaching an inflection point where technology itself is paramount to meeting the demands of the fourth industrial revolution. They look to China as a development partner who will aid in those initiatives.

African actors are realizing that we’re reaching an inflection point where technology itself is paramount to meeting the demands of the fourth industrial revolution. They look to China as a development partner who will aid in those initiatives.

GSAS Communications: How did we get here? What’s the arc of the relationship between Africa and China?

Jili: During the Cultural Revolution and into the 1970s, China retreated into itself. After the big opening under Deng Xiaoping in 1979, China mostly prioritized relations with Europe, the US, and Japan to sustain its development. Beginning in the 1990s, China started to look outwards to expand its economic reach. That’s when you started seeing great activity, not only from the Chinese state but also from Chinese corporations, mostly in East Africa.

Commodities like coal, wood, and oil have always been primary ways that African states have secured the financial means to sustain their societies, so their engagement with China on that front was not particularly surprising. But China’s rhetoric was a bit different from Western actors. To receive aid and support from the West, African states needed to conform either to market or democratic reforms. China maintained a kind of neutrality as relates to some of these key questions. That meant that African nations could engage with China on terms that were politically and economically viable for them.

So, what began in the 1990s with extractive industries led to an increase in investment and aid from China. In 2014, China made the big announcement about the $1T Belt and Road Initiative. Today, nearly 40 countries have signed on. It’s a focal point for them in getting the infrastructure necessary to support domestic development.

GSAS Communications: Neither Kenya nor Ethiopia have the raw materials China wants, nor do they have a big consumer base for Chinese products. Yet China has made major investments in both countries. What happened there?

Jili: To some extent, I think other countries in Africa just need to negotiate better when they engage with China. I mean, if you're a big oil producer or a big coal producer, China may not initially have come in with the ambition of developing your tech sector, but that initial interest doesn’t mean it will be the only interest. These countries need to be able to play on multiple fronts.

But yes, Kenya and Ethiopia are outliers because they didn’t have major extractive industries or large consumer bases. They were able to negotiate investments by China in their information and communication technology sector. Why did China invest? I think that it’s quite responsive diplomatically to the wants of African nations. Success in Kenya and Ethiopia support China’s claims of being a unique development partner and refutes charges that it’s just another colonial power.

GSAS Communications: So, it’s part of China’s “no strings attached” approach to investment, aid, and support in Africa?

Jili: Yes, it’s about distinguishing themselves as a development partner from western partners who did come with prescriptions for democratic and economic reform. It’s about saying, “Hey Africa, we’re not like them.” It emphasizes political sovereignty and political equality among global South actors. And that’s key because China’s engagement can in some ways harken back to the asymmetry that was at the heart of colonialism. That’s why China is trying to distinguish itself from the western actors of the past who spoke about democratic values while undermining the sovereignty of African countries.

GSAS Communications: So, how does that approach work in practice? Are there really “no strings attached”?

Jili: No strings are attached between the financing of the infrastructure projects and political ideology. But a kind of string is attached, for example, when an African country uses oil as collateral in a deal. If a country fails to pay off its loans, the lenders get access to oil fields for a designated period of time. That posture itself is beguiling, but it also obfuscates a kind of economic asymmetry that still does exist between both Africa and China. It presents political equality, but then ignores economic inequality between the actors; it dislocates the actual connection between a failure to pay and using raw materials as collateral in the future.

If you're an African country and you know you don't have anything else beyond your raw materials, offering those as collateral allows you to get access to loans you might be able to use for development. But that’s not necessarily a good thing for every country, especially those with unstable political histories or connections to human rights violations. This is where the responsibility is not only on African actors, but also on China, which goes into deals with countries that are more mismanaged, or where we know there are gross human rights violations. Through its support of these regimes, China is causing harm on the ground.

GSAS Communications: You’re a cybersecurity analyst who’s written extensively about the Safe Cities Project initiated by China’s Huawei corporation, which provides surveillance technology to African countries. Is this one way China could be causing—or at least supporting—“harm on the ground?”

Jili: The Safe Cities Project from the vantage point of African actors is really about providing the technological means to meet development ambitions. These “smart cities” acquire technology that’s necessary to improve domestic capacity on the manufacturing front and function as catalysts that accelerate economic development. But they also provide technologies like facial recognition and social media monitoring to the police to improve surveillance, curb crime, and improve administration.

What my work shows, however, is that a direct correlation doesn’t exist between facial recognition technologies and crime reduction. In fact, that kind of hyperbolic assumption in many ways further obfuscates the sociology of crime. Crime in itself is not tied up with the absence of technical means; crime is connected to questions of poverty, and race, and social factors that surveillance and policing ignore. And when Chinese suppliers ignore that, they exacerbate the situation on the ground.

That in itself does not mean that these technologies shouldn't be purchased or shouldn't be put to use; it raises the question of how they should be best used. Legislative regimes in Africa need to think about how facial recognition can be utilized to meet governance needs while simultaneously attending to the broader sociology and anthropology of crime.

GSAS Communications: So, is the notion that China is trying to export authoritarianism through the sale of surveillance technologies to Africa overblown?

Jili: Indeed. In a lot of ways, I think it is overblown. It assumes that China’s activity in Africa is the expression of some grand strategy. In reality, its activity is contingent on the regime, economic arrangement, and political circumstance in each country. That’s why China is equally willing to work with an authoritarian government and a democratic government. If we don’t put Beijing’s actions in the context of its behavior globally, it is too easy to see it as exceptional and ignore the local conditions that induce its actions.

At the same time, China’s “neutrality” is not benign. It’s simply contingent on the promotion of state sovereignty and the absence of political conditions. It frames relations in a way that does not disrupt economic activities, which remain asymmetric, while eagerly promoting political equality. This obfuscates the fact that, while offering aid and loans, Chinese support enables state-led surveillance. So, its supposed “no strings attached” approach does not result in neutral outcomes but is a camouflaging mechanism that maintains China’s image as a generous development partner, while also deemphasizing economic inequality and its impact on local political environments.

[The notion that China is exporting authoritarianism] assumes that China’s activity in Africa is the expression of some grand strategy. In reality, its activity is contingent on the regime, economic arrangement, and political circumstance in each country.

How long China maintains this posture of “neutrality” matters as it further expands its geopolitical footprint in Africa. Unfortunately, the few publicly available Chinese state documents remain vague in regard to regulating African investments. They lack explicit direction, legally enforceable obligations, and effective accountability measures to mitigate the misuse of digital surveillance. It is this blind spot that enables Chinese corporations to adapt to host country ambitions, even at the expense of civil liberties.

Photos by Tony Rinaldo and Courtesy of Bulelani Jili and Shutterstock

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast