Fighting Breast Cancer in Rural America

Research recognizing the diversity of rural communities offers new solutions to public health challenges

When Jennifer Cruz was 13, she lost her mother to brain cancer that had metastasized from late-stage breast cancer. In their small hometown of Wapato, Washington, the scarcity of public health resources turned an otherwise preventable or treatable illness into a tragedy.

“It wasn’t necessarily because she was predestined—she didn’t have the genetic stuff,” Cruz explained. “It was really lack of access, late detection, and limited treatment options.”

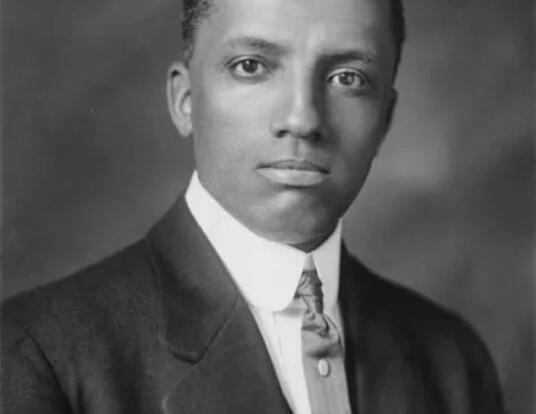

This realization ignited a lifelong passion for addressing health inequities. Cruz, who graduated from Harvard’s Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in May 2025 with a PhD in population health sciences, arrived on campus with the explicit goal of improving health care access in communities like Wapato.

“Given the opportunity to study and be at one of the most elite institutions in the world, I really had the choice to do anything. But if I was going to pour resources into something and have obligations back home, it made sense to do some work that was relevant to that,” she says. “I focused on breast cancer because of that direct tie. While going through higher education and having access to resources, I’ve always stayed rooted in where I’m from and the people and the communities that raised me.”

[My mother’s death] wasn’t necessarily because she was predestined . . . It was really lack of access, late detection, and limited treatment options.

–Jennifer Cruz, PhD ’25

Beyond John Deere

As she dove into social epidemiology, Cruz was disheartened by the lack of emphasis on rural communities. “No one was talking about rural settings or rurality overall. There’s this assumption that when we’re talking about people and populations, we’re talking about urban settings—we’re talking about neighborhoods, we’re talking about cities,” she explains. “We’re not thinking about these small rural towns or really anything that’s outside of them. It’s just not what comes to mind.”

On the flip side, Cruz says, when researchers and policymakers do highlight rural communities, they emphasize a stereotype of rurality rather than representing the diversity of rural America. “They’ll put up a picture, and it’s like a guy on his John Deere tractor, and he’s probably white, and he’s got on overalls and an old hat,” she jokes.

Cruz knew from her own experience that this image was an inadequate representation of rural America. The goal of her PhD research was to translate this lived intuition into innovative, mixed-methods research that would establish a system for classifying different types of rural communities. According to her adviser, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Professor of Social and Behavioral Sciences Karen Emmons, Cruz’s research instincts were spot-on.

“Jen grew up in a rural setting and understands from her own experience that where one lives influences one’s health,” Emmons explained. “She felt that, just like the differences observed across urban neighborhoods, there are many differences across rural settings. But rurality has always been defined based on population density, and not characteristics of the environment, economy, or people who live there.”

Unique Traits, Unique Challenges

To create a more fine-grained definition of rurality, Cruz’s research involved three interconnected projects. Her first step was to use latent class analysis, a computational modeling technique that clusters entities into distinct groups based on shared characteristics, to systematically identify different types of rural places.

“I used publicly available information from nine different sources and built this enormous data set to look for patterns across every rural census tract in the U.S.,” she says. “A lot of it came down to the geography of how concentrated folks were. Were they in smaller towns, or were they far and stretched out? And then within that, are they more remote or centralized? Do they have resources or not?”

Her analysis, which was also published as a standalone paper in the journal Social Science & Medicine – Population Health, revealed four distinct types of rural communities: outlying, developed, well-resourced, and adaptable. Each is defined by a unique combination of demographic traits and structural features—such as plumbing access, poverty rates, walkability, and homeownership—and exhibits distinct public health challenges. To assess the validity of this classification structure, Cruz then returned to her hometown in the Yakima Valley to conduct interviews and focus groups with local stakeholders.

“The aim was to take the quantitative differences and say, okay, statistically that means one thing, but on the ground, does it hold?” she says. The qualitative results corroborated her initial quantitative analysis, affirming the diversity and complexity of rural areas even within the same county or region. “Depending on where you’re at, you need to think critically—there are these differences, but there are a lot of overlaps.”

Her third and final step was to connect this typology of rural places back to the public health issues that initially motivated her dissertation. She used agent-based modeling, a type of computer simulation that models interactions between people over time, to predict how interventions designed to improve breast cancer screening rates might play out in different types of places.

“If we do have these four different types and we don’t have a lot of resources to intervene, we should probably figure out which interventions or what types of interventions might make the biggest impact,” Cruz explains. Using breast cancer screening as the desired outcome, she built a prototype model to explore how communities with various demographic characteristics might respond to different changes to their context, such as increased social connectivity or decreased insurance coverage.

Social and Structural Strength

Across the different types of rural communities, Cruz found that social connectivity was essential for overcoming structural barriers to breast cancer screening, including a lack of insurance. “Social connectivity can function as a pathway for sharing information, reinforcing norms, and facilitating care access,” she says. Despite the importance of community ties, Cruz emphasizes the continued need for structural solutions. “Strengthening social connectivity should be seen as a complementary strategy, most effective when paired with efforts to expand insurance coverage, reduce poverty, and ensure equitable health care infrastructure across rural settings.”

Jarvis Chen, the associate director of graduate studies for the Population Health Sciences PhD program, praises Cruz’s work for highlighting the importance of social connections. “It’s contributing to an assets-based framing for rural health—one that acknowledges the challenges facing rural communities but also the strengths and resilience factors communities build through their social relationships and connections,” he said. “I see this work contributing to individual and community-based interventions that build on the diversity and strengths of communities to improve health outcomes, in particular around cancer screening and prevention.”

Social connectivity can function as a pathway for sharing information, reinforcing norms, and facilitating care access. Strengthening social connectivity should be seen as a complementary strategy, most effective when paired with efforts to expand insurance coverage, reduce poverty, and ensure equitable health care infrastructure across rural settings.

–Jennifer Cruz, PhD ’25

Emmons agreed that the simulation model was one of Cruz’s most novel and impactful contributions, with potential applications that extend far beyond the specific case of breast cancer screening. “It is a really innovative way to try out possible intervention approaches, letting one figure out which approaches have the greatest potential for impact before large intervention studies are launched,” she notes. “This approach can be applied to a wide range of health care outcomes, beyond breast cancer screening. For the first time, the field is able to consider rural settings as heterogeneous entities, and to make selections for intervening that may provide the best likelihood of improving health.”

Listening for Solutions

In addition to proactively modeling the impact of interventions, Cruz’s dissertation research offers a powerful accountability tool for monitoring the distribution of resources to rural communities. “We know that the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) gives money out, but are they giving it to one type of rural, the affluent place that probably has a more well-functioning health system?” Cruz questioned. “To focus on health equity and more broadly health justice, you have to be thinking about where these resources are going. If you are agnostic to it, then you’re going to actively disadvantage people when the goal of HRSA is to invest in rural infrastructure.”

Cruz is now the associate director of noncommunicable diseases at the New York Academy of Medicine, where she has continued to work on high-impact public health issues afflicting rural and urban communities in New York City and across the country.

I see [Cruz’s] work contributing to individual and community-based interventions that build on the diversity and strengths of communities to improve health outcomes, in particular around cancer screening and prevention.

–Jarvis Chen

Senior Lecturer on Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

“It’s all work that’s directly tied to things that matter,” she says. One of her current projects investigates the impact of de-implementing race-based clinical algorithms, a move toward closing racial health inequalities. “Even when you do have access, the systems are actively disadvantaging communities of color. So that’s some of the stuff I’m doing now. I’m still doing some rural health and trying to build that out actively.”

In this new role, Cruz hopes her PhD from Harvard will help legitimate the solutions that communities have already found for their own problems. “I don’t value being the smart person. I value working with communities . . . uplifting what they’re saying,” she says. “People know what the solutions are—it’s just that no one’s listening.”

As for her research, Cruz hopes that policymakers and community organizations will continue to make use of the rural classification system to better plan and assess public health interventions. “My intention was never for this to sit in an institution. It was made to be used.”

Jennifer Cruz’s research was supported by a National Institutes of Health T32 training grant (2T32CA057711-28).

Banner image from Wikimedia Commons

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast