How Growth Happens

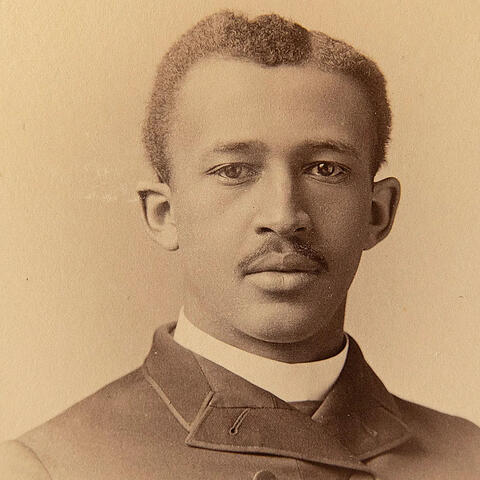

Aghion, PhD ’87, wins Nobel Prize in Economics for work on "creative destruction" and innovation

Philippe Aghion, professor at the Collège de France and INSEAD, Paris, and at the London School of Economics and Political Science, slept well the night before the announcement of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics.

Since then, not so much.

“I was totally sure that this year’s prize would have nothing to do with me,” he says. “So I was very surprised when I saw the Swedish country code—46—on my phone. Then they told me, ‘Look, good news for you,’ and so on. It’s still unreal for me. I haven’t gotten much sleep since.”

Aghion joined colleagues Peter Howitt and Joel Mokyr as winners of the 2025 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth.” The 1987 PhD alumnus of the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Harvard Griffin GSAS) and longtime Harvard economics faculty member hopes his insights will help policymakers better understand the dynamics of “creative destruction,” as well as the need to manage that process so that incumbent firms don’t stifle new innovations—and workers aren’t left out in the cold.

Creating Growth

“Creative destruction” is a term coined by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter to refer to the process whereby new innovations displace old technologies. Aghion and his Brown University colleague Peter Howitt won their share of the 2025 Nobel for a 1992 article that “constructed a mathematical model” for the process.

“It’s a world where new entrants and new talents constantly challenge existing ones,” Aghion explains. “They expect that if they innovate, they will get innovation rents—extra earnings firms get from an advantage others can’t yet copy.”

[Creative destruction] is a world where new entrants and new talents constantly challenge existing ones.

2025 Nobel Laureate Philippe Aghion

As an example, think of your smartphone. Fifty years ago, consumers almost exclusively had landlines. Twenty-five years ago, cellphones began to displace them. Today, the smartphone has displaced both—along with the photo and video camera, the CD player, and even the radio. “So many products have become obsolete with the advance of the smartphone,” Aghion says. “That’s creative destruction. Those who invented new products were seeking rents, of course.”

Pol Antràs, Harvard’s Robert G. Ory Professor of Economics, says that Aghion and Howitt formalized the notion that Schumpeter’s process of creative destruction generates long-run growth. “In their theoretical framework, profit-seeking entrepreneurs innovate and, by doing so, render previous technologies obsolete, ‘destroying’ the rents of incumbent firms. This ‘creative destruction’ mechanism captures Schumpeter’s idea that progress requires the replacement of old technologies by new ones. Relative to other theories relating innovation to long-run growth, their theory generates a tight and realistic link between market structure and innovation.”

Barriers to Entry

But Aghion’s work also highlights a contradiction in the creative destruction process: firms on the winning end are inevitably tempted to use their rents to defend their dominant position in the market and prevent new innovation. “Microsoft was involved in antitrust cases, as were Amazon and Facebook—superstar firms that initially harnessed the IT revolution so well,” he says. “Initially, these firms boosted growth in the U.S. between 1995 and 2005, but since 2005, growth has been dampened because they became so pervasive that they ended up discouraging new firms. The entry rate of new firms has fallen in the U.S. since the 2000s.”

The solution, Aghion says, is for governments to regulate market economies so that they strike the right balance. “We need to provide incentives for future innovation, but also ensure that innovators don’t deter the entry of new talents and new firms. Fast-growing economies are those that manage this contradiction well.”

Relative to other theories relating innovation to long-run growth, [Aghion and Howitt’s] theory generates a tight and realistic link between market structure and innovation.

Pol Antràs, Robert G. Ory Professor of Economics

If countries want to pursue industrial policy or pro-innovation policy to help incumbent firms innovate more, Aghion says, they have to make sure not to deter new entry. “When you design industrial policy, you have to factor in entrants. That’s a direct implication of our approach.”

Aghion cites DARPA, the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, as an example of a well-designed industrial policy that both preserves the incentives of rent and allows for entry. “In defense and space, the money comes from the government, and they pick team leaders from industry or academia,” he says. “For a three- or five-year period, those team leaders can elicit competing projects. So, there’s a top-down part and a bottom-up part. That was the case with DARPA, and also with BARDA—the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority—which supported competing labs producing mRNA vaccines.”

Winners and Losers

The Nobel Committee’s announcement also noted that “when a new and better product enters the market, the companies selling the older products lose out.” Creative destruction means new firms and exiting firms, job creation and job destruction. So, just as governments need to regulate markets to ensure incumbent firms don’t discourage new innovations, Aghion says, it’s important to have a system that supports those displaced by the churn of technological change.

“The Danish ‘flexicurity’ system is a model,” he says. “In Denmark, when you lose your job, for two years you receive 90 percent of your salary, and the state retrains you and helps you find a new job. That makes creative destruction work better, which is good for innovation, but it also protects individuals.”

In Denmark, when you lose your job, for two years you receive 90 percent of your salary, and the state retrains you and helps you find a new job. That makes creative destruction work better, which is good for innovation, but it also protects individuals.

Philippe Aghion

As an example of his research’s ongoing relevance, Aghion points to The Future of European Competitiveness, the 2024 report authored by former European Central Bank president and Italian prime minister Mario Draghi. The report showed the European Union (EU) lagging behind the U.S. and China in technological innovation and recommended greater integration of Eurozone markets, the development of an innovation ecosystem, and significant increases in funding for research.

“The Draghi Report reflects much of the kind of work I’ve done,” Aghion says. “If you want innovation rents, you need a big market and more competition, because firms innovate at the frontier to escape competition. You also need venture capital, institutional investors, and a culture that encourages risk-taking. And we need something like DARPA in Europe, and more support for basic research. The European Research Council is not enough. Universities need better funding and more investment. A flexicurity system like they have in Denmark is something I would add to the report.”

Hurrahs from Harvard

Aghion’s colleagues at Harvard were thrilled by the announcement of his Nobel. “I was delighted to hear the news,” says Lewis P. and Linda L. Geyser University Professor Oliver D. Hart. “Philippe has not only done pathbreaking work on growth but also pioneering work in my own area, the theory of contracts and organizations.”

Aghion taught at Harvard from 2000 to 2015 and is remembered warmly by the faculty here. “Philippe was a wonderful presence in the Economics Department,” says Xavier Gabaix, Pershing Square Professor of Economics and Finance. “We all remember his booming voice, always filled with boundless enthusiasm. He was constantly bubbling with energy, thrilled by the connections between new ideas he was forever generating.”

Antràs was particularly excited to hear of his old colleague’s honor. “I shared a wall with Philippe when I first joined Harvard in 2003, and we became close friends,” he says. “He actually attended my wedding in Spain in 2005. More generally, he was a great mentor and was very supportive when I was trying to navigate being a junior faculty member at Harvard.”

Aghion says that the Nobel is an acknowledgment of a new model—one that puts firms at the heart of the process, in which growth is driven by a continuous flow of new entrants and new innovations challenging existing firms. He hopes the work recognized by the award will further promote its understanding and use by new generations of economists and policymakers.

“There is now a new growth paradigm—the Schumpeterian growth paradigm,” he says. “Peter Howitt and I did the original model, and younger economists have since developed extensions and tested them. Joel Mokyr brought in the historical perspective. Already, major reports such as the World Development Report and the Draghi Report are built on this framework. Younger generations studying growth mainly use our approach. The Nobel recognition will give it a new boost.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast