The Generosity of Being You

Notes from a Writer's Desk

The fall term is winding down, the holidays are right around the corner, and you find yourself at a festive gathering on campus. You meet someone from a different department, and immediately after the introduction, they ask the inevitable question: “What do you do?” In this setting, you can only interpret the question to mean one thing: “What do you research?” How do you respond, and how do you feel about your response?

While research is particular to academia, the question, though vague on the surface, likely prompts a parallel reaction from most people; unless there is a final qualifying phrase (e.g., “What do you do in your free time?”), we assume the questioner is referring to our line of work. It’s true that jobs, in general, do take up much of our waking time. But for academics, deep intellectual inquiry is not simply what we do; it’s who we are. Indeed, it is pervasive both in our waking and sleeping states. In this sense, it’s more of a vocation than a job. You cannot simply leave the office and turn off your mind, the single most important tool of the trade.

There are positives, to be sure, from being able to carry our work with us. Yet we also risk becoming consumed by it, burning out, and losing any sense of joy that we may have had. At this time of year, especially, it’s common for enthusiasm to lag and easy to feel like you’ve lost the bigger picture of what it is that you’re doing—whether you’re caught up in the frenzy of meeting deadlines or deep in the weeds of dissertating. The winter break, however, offers a perfect opportunity to step back, reset, and reflect not only on what you’re doing, but on how and why you’re doing it. To reflect on what matters to you.

For one thing, giving yourself some distance from actual research—and from the mental grind—can be a reminder that you are more than your work and that you can find joy and meaning in other kinds of activities. To this end, the break allows you to pick up old hobbies or to try new things. Perhaps you enjoy cooking and baking and now have more time to experiment. Perhaps you are a scientist by day, and a musician or poet or artist by night. Perhaps you enjoy hiking or other outdoor activities. Regardless of what you do, having some balance in life is important.

But I am not suggesting a complete detachment. The downtime also provides an opening for metacognition, which implies something different, something active; if there is a distancing, it is only to get understanding. Part of your joy can and probably does derive from the intellectual work itself. It’s just easier to let that joy in when you remember why you care about your research in the first place. Consider the social situation described above. Are you excited by the opportunity to talk about your research? Reluctant? Neutral? When you think of other professional settings or activities, such as conference or seminar presentations that may be looming, do you feel nervous about sharing your work? Do you have conviction in your ideas?

If you are hesitant, you are not alone. Perhaps you don’t want to sound pretentious or perhaps you are worried that senior colleagues in the field will dismiss your ideas. Overcoming these concerns could be a matter of believing in what you do, and of altering your perspective. As a colleague from another university recently expressed, it can be helpful to think of presenting your ideas not as a stressful task or a burden unto others. Rather, speaking is an act of generosity. Tell yourself: I have particular information that others may not have, and I am generous enough to share it.

Hearing this advice, I worried that such an attitude could devolve into, or be interpreted as, arrogance. Indeed, there is a fine line between the generosity of sharing knowledge—which includes both enthusiasm and respect—and outright condescension. But the distinction is in the way you describe your research, the story you tell and the tone with which you tell it. Just as important as what you say is how you say it. It’s also where your own investment makes a critical difference—do you have a genuine passion for what you do and a desire to share that with others? Passion is a four-letter word in academia, so let’s dial it back and ask a simpler question: do you care about what you’re saying? If not, it will be obvious to listeners. You can’t really expect others to care if you don’t.

This, again, is where metacognition can be so valuable. We do this all the time in an informal manner, but reflecting intentionally on your intellectual autobiography and process entails thinking carefully about what sparked your initial interest in the field, about why you pursue certain questions, and about why those questions are meaningful in both a microcosmic and macrocosmic sense. On a practical level, this practice translates directly to things like personal statements and interviews, but it also helps you rediscover why it is that you got into your area of research in the first place. The exercise, moreover, becomes an act of narrativizing, of storytelling, and this, in turn, informs how you might tell a story to others. It is through storytelling that we persuade, that we guide our listeners or readers on a journey to a shared moment of discovery.

The generosity of sharing takes on its true significance when you understand why the content you’re sharing matters and when you are able to convey that message to others in an effective manner. Being a generous conversationalist means including others, not lecturing; as long as you keep that in mind, you should embrace opportunities to talk about your ideas, to brainstorm, to see what questions or feedback you get. The winter break is a good time to engage not only in metacognition, but also in conversation with different interlocutors. How would you talk about your research with family members or old friends, for example? What would resonate with them? What story would you tell?

These informal settings can be great practice for more formal presentations, even if the register and detail might change. In the end, both are important because both accomplish a fundamental premise of intellectual pursuits: sharing knowledge with others. It is an act of generosity that adds to the collective wisdom and well-being of humanity. And it is an act of generosity that is particular to each individual. What better time than the holidays to remember how to be generous?

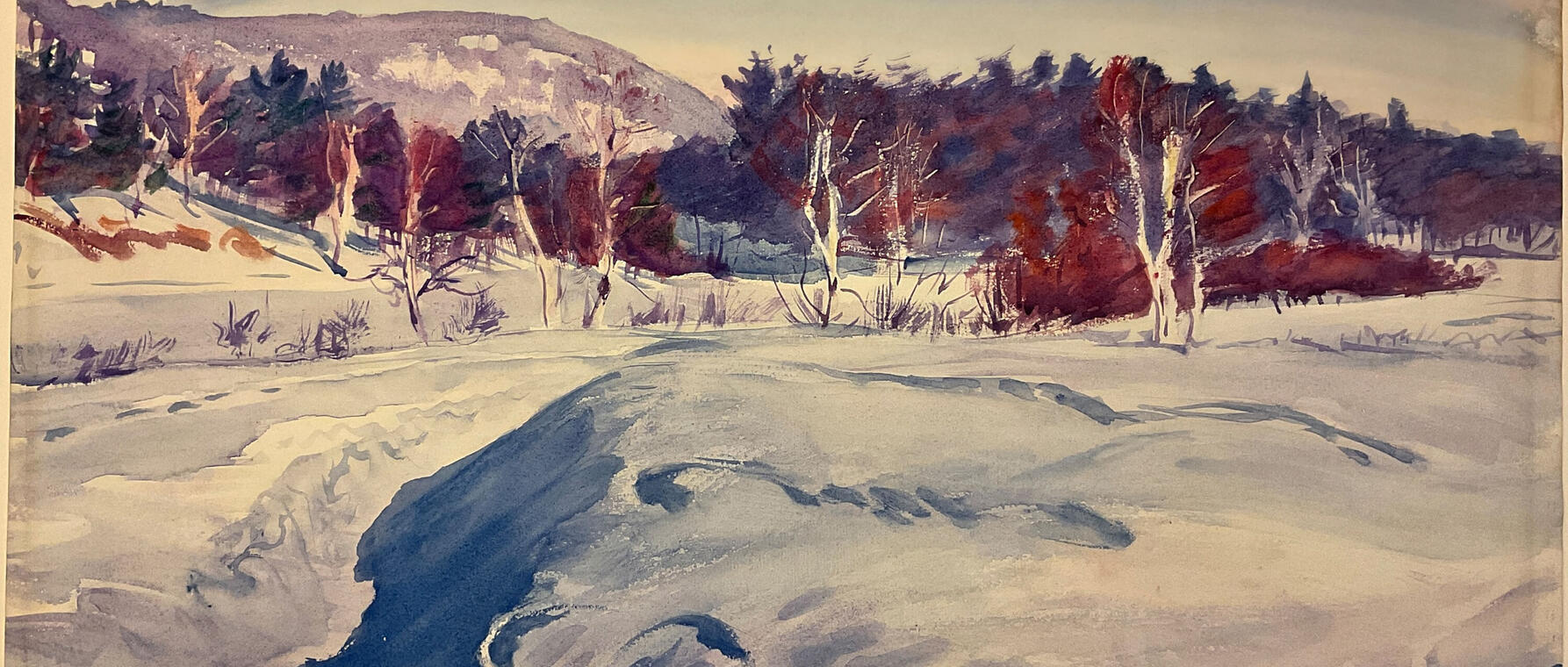

Banner Image: Dodge Macknight, Winter Landscape, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum (1917.9).

Ready to book an appointment with FWC staff? Access the FWC intake form.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast