Foundational Leaders

The 2025 Centennial Medalists established the basis for new knowledge and new fields of study

The 2025 Centennial Medalists established the basis for new knowledge and new fields of study. They include a co-founder of Partners in Health and former president of the World Bank, and a paradigm-shifting evolutionary geneticist whose work informs criteria for evaluating extinction risk. All of this year’s honorees are renowned for building the foundations of their disciplines.

Lorraine Daston, PhD ’79, History of Science

Lorraine Daston, a leading historian of science and director emerita of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, developed her passion for books as a child—just like her father, who grew up in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston and was determined to read through the shelves of Boston Public Library “from A to Z,” by Daston’s account.

Daston experienced the same impulse when she arrived at Radcliffe College in 1969. “Should there be a heaven for scholars,” she says, “it is surely Harvard’s Widener Library,” home to a wealth of scholarship on astronomy, mathematics, physics, and the sciences, where Daston was destined to make her mark as a historian.

A first step on that journey came by way of Katharine Park, PhD ’81, Samuel Zemurray, Jr. and Doris Zemurray Stone Radcliffe Research Professor of the History of Science, emerita, who befriended Daston when they were both undergraduates at Radcliffe and recommended that she take Natural Sciences 9: “The Astronomical Perspective,” a legendary course taught by Harvard historian of science Owen Gingerich, PhD ’62.

“Raine has a gift for friendship,” says Park, “and—it’s not coincidental—a real commitment to collaborative work, to the idea that you get ultimately much farther working with people, particularly people whose fields are not necessarily congruent with your own. It’s one of the reasons Raine’s scholarship is so extraordinary: she’s brought people together and opened herself up to collaborations with people from very different fields.”

After completing her PhD in 1979 and teaching at Harvard, Princeton, Brandeis, the University of Göttingen, and the University of Chicago, Daston became one of the first directors of the Max Planck Institute. In that role, she built one of the world’s leading centers for the history of science from the ground up after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War.

“I think that it’s a myth that the humanities are in some way unsuited for collective scholarship,” Daston observes. “My experience, thanks to the possibilities afforded by the Institute, was exactly the opposite. For me, the best way to think is in conversation with someone, and I’ve been lucky to have superb interlocutors.”

Daston’s distinguished body of work focuses on what she calls the “history of the self-evident”: concepts and ways of thinking—such as probability, objectivity, wonder, and rules— that we take for granted in everyday life. “What is thinkable?” Daston encourages us to ask. “What is unthinkable? Why is it that we have such difficulty imagining our way into different systems of thought, be they past or simply of different cultures?”

I think that it’s a myth that the humanities are in some way unsuited for collective scholarship. My experience, thanks to the possibilities afforded by the Institute, was exactly the opposite.

—Lorraine Daston

Director Emerita, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

Understanding and analyzing these differences feels more urgent than ever, and Daston’s current projects reflect issues that loom large in global consciousness today. One project traces the history of the concept of natural disasters, which, Daston startlingly observes, recently drew to a close. “We have lost the category of a natural disaster for which no one is at fault,” Daston points out. “We do not believe human beings create Category 5 hurricanes, but we certainly believe that people fail to maintain dikes and levees to make proper preparations for the worst—and of course, in an age of global climate change, none of us are innocent of the disasters that have struck people all over the world.”

Her advice for students who dream of following in her footsteps? “Learn as many languages as you can,” Daston urges. “And go to Widener!”

Jim Yong Kim, PhD ’93, Anthropology

For Jim Yong Kim—the first student in the history of Harvard’s dual MD/PhD program to pursue a doctor of philosophy degree in the social sciences, who revolutionized global health care delivery when he co-founded Partners In Health with his classmate, the late Paul Farmer, PhD ’90—graduate study in anthropology laid the groundwork for everything he would go on to do.

“I use my medical training not infrequently, but I use my anthropology training every day,” Kim explains. “In anthropology, the task is understanding what it means to be human, and how cultural difference and social class shape what it means to be human in a particular place at a particular time. For me, it doesn’t get better than that: to be able to contemplate these enormous issues with some of the smartest people you’ve ever met. Graduate school was one of the great periods of my life.”

With Partners In Health, Kim and Farmer proved something previously unimaginable: that it is possible to move beyond disease prevention and bring state-of-the-art, life-saving treatment to some of the poorest areas of the world. Partners In Health tackled HIV/AIDS and drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) in Haiti and Peru, success stories that paved the way for Kim’s appointment as a director of the World Health Organization and his leadership of the “3 by 5” initiative, which set a goal to treat three million people in Africa for HIV/AIDS by 2005 and more than tripled access to antiretroviral medication on the continent.

This was only the first of many dramatic transformations that Kim was destined to effect. In 2009, he became president of Dartmouth College, where he founded a new program in health care delivery science, a field now well represented across universities worldwide. Three years later, President Barack Obama nominated him to serve as president of the World Bank, where Kim set an ambitious goal for reducing global poverty, secured financing for climate change response, and emphasized mental health as a global priority.

In anthropology, the task is understanding what it means to be human, and how cultural difference and social class shape what it means to be human in a particular place at a particular time. For me, it doesn’t get better than that.

—Jim Yong Kim

Co-Founder, Partners in Health

Kim’s work today includes serving as vice chairman of Global Infrastructure Partners, bringing private equity investment to critical infrastructure projects in developing countries, and as chancellor of the University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda, established in 2015 by Partners In Health, now ranked as one of the top four universities in sub-Saharan Africa.

“There’s a rarity to Jim: a uniqueness, a singularity to his career,” says Kim’s MD/PhD advisor Arthur Kleinman, AM ’74, Esther and Sidney Rabb Professor of Anthropology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and professor of medical anthropology in global health and social medicine and of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. “He’s moved between radically different institutions, and he’s done transformative work at each place. He gets institutions to do things you would never, ever think they would do. He’s an astonishing figure, and he’s achieved at the highest level. He shows you what a leader is.”

Kim encourages today’s students to fully leverage the power of their education. “We were still trainees at Harvard when we took on enormous global issues like drug-resistant TB and HIV, and we gained so much strength from the fact that we were at Harvard,” Kim observes. “We made the best possible use of our connectivity to the university to speak up on behalf of people who didn’t have a voice. Anyone who has the good fortune of being a graduate student at Harvard should ask themselves, ‘Given the ridiculously wonderful, elaborate nature of my education, what is my responsibility to the world?’ Paul and I came up with one particular answer; everyone will have a different one.”

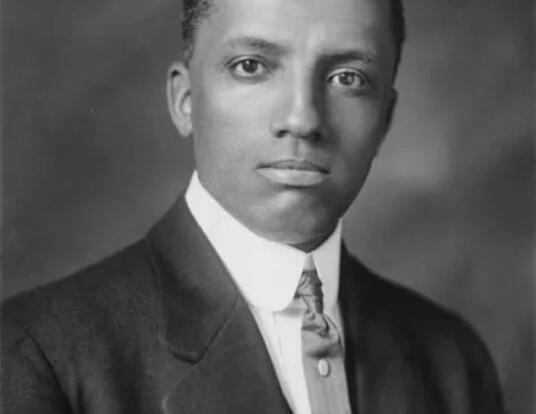

Russell Lande, PhD ’76, Organismic and Evolutionary Biology

Russell Lande works on some of the biggest questions you can ask in science: How did we get here? How can we understand the complexity of life on Earth? And where are we going?

“From very early on, I always thought that evolution was one of the most fascinating subjects that humans could possibly consider,” says Lande, an acclaimed population biologist and professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego, and Imperial College London. As an undergraduate at the University of California, Irvine, Lande started out as an organic chemist but took classes for majors across a broad swath of disciplines—physics, chemistry, biology, and math. After going on field trips with graduate students in deserts and mountains across Southern California, he turned his attention to theoretical ecology.

Lande spent a year in graduate school at the University of Chicago before making the move to Harvard with his adviser Richard Lewontin. Lande began studying evolution, and in the process, he connected the dots across different areas of science—and across time—in a way that would revolutionize the field.

The story stretches back to the early twentieth century, when the work of Gregor Mendel was rediscovered after languishing in obscurity for decades, leading to intense debates about the mechanisms driving genetic inheritance. These debates were resolved by the development of quantitative genetics—which enabled the statistical analysis of genetic variation—as well as modern statistics itself, now ubiquitous across the sciences and social sciences, but invented first and foremost to answer these questions about genetics and evolution.

After learning about the existence of quantitative genetics, I realized fairly quickly that nobody in ecology or evolution, broadly speaking, knew the first thing about it.

—Russell Lande

Professor Emeritus at the University of California, San Diego, and Imperial College London

Remarkably, in the decades that followed, these insights were largely forgotten in academic circles. “After learning about the existence of quantitative genetics, I realized fairly quickly that nobody in ecology or evolution, broadly speaking, knew the first thing about it,” Lande explains. This put him on a path to establish new foundations for the field, including a landmark paper in 1983 with S.J. Arnold on continuously varying “correlated characters”: traits, like height and weight, that are influenced by many genes and a wide variety of environmental factors.

“This was a major advance in the field and got people thinking about correlated characters and evolution in a completely different way,” says John Wakeley, professor of organismic and evolutionary biology. “It spawned subfields of evolutionary thinking that would not have happened otherwise.”

Lande has had a similarly powerful influence on high-stakes environmental conservation efforts. His work serves as the basis for the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List Criteria for extinction risk, and he has provided expert testimony on the importance of land conservation and biodiversity—leading, most famously, to the protection of the northern spotted owl in the Pacific Northwest in the late 1980s.

“As a student, I was interested originally in the stability of ecological systems in the face of human perturbation, because it was pretty clear even then that the human population was on course to destroy the planet, its environment, and its own civilization,” he says. “We are now in one of the great waves of mass extinctions in Earth’s history, and very little is being done to stop it.”

Lande offers a stark reminder: “Certain things can’t be compromised, or else they just disappear,” he observes. “You cannot keep compromising.”

Mary Beth Norton, PhD ’69, History

Historian Beth Norton has been blazing unexpected trails her entire career. A former president of the American Historical Association and the first woman to be appointed to the history faculty at Cornell University, where she taught for 47 years, she played a leading role in establishing the field of colonial American women’s history—but she began her journey as a historian with neither women nor colonial America in mind.

“As an undergraduate at the University of Michigan,” Norton says, “I thought the colonial period was the couple of weeks you got through before you got to the interesting stuff in the nineteenth century.” But in her second semester of graduate school at Harvard, she had what she calls a “conversion experience” in a seminar on colonial America. “There was something about that material that just grabbed me,” Norton reflects. “The people of the mid-eighteenth century in Boston reached out to me over the years and said, ‘Why didn’t you ever pay any attention to us before?’”

Norton’s dissertation, on Loyalists who fled America for England during the Revolution, won the Society of American Historians prize for the best dissertation on American history that year. “When I did my dissertation, I wasn’t very interested in women,” Norton says, “but because the Loyalists that I worked on had gone to England and had female relatives in America, I read a lot of letters from women.”

This put her in a perfect position to notice statements that rang false about colonial women in early scholarship on American women’s history, a field that began to emerge shortly after she completed her PhD in 1969. “The first articles focused on the early 19th century, and the authors made assumptions about women in the 18th century that I thought were incorrect,” Norton explains. By painstakingly reviewing archival materials from the period, she was able to set the story straight, producing scholarship that defined the fledgling field, including Liberty’s Daughters in 1980; Founding Mothers and Fathers, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, in 1996; and Separated by Their Sex in 2011.

Mary Beth Norton was first out of the gate in the 1970s and 1980s with her books on Loyalists and on women in the American Revolution. But she also surprised lots of people by taking on a topic that had been pioneered by others.

—Laurel Thatcher Ulrich

300th Anniversary University Professor, Emerita, Harvard University

“What most impresses me about Mary Beth Norton—other than her relentless energy and enthusiasm—is her capacity to pioneer new topics and give new life to old ones,” says Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, 300th Anniversary University Professor, emerita. “She was first out of the gate in the 1970s and 1980s with her books on Loyalists and on women in the American Revolution. But she also surprised lots of people by taking on a topic that had been pioneered by others—New England witch-hunting—and saying something new.”

Norton won the Ambassador Book Award in American Studies for her 2002 book on Salem, In the Devil’s Snare. “I thought I was going to write a feminist reinterpretation of the witch trials,” Norton says. The project changed direction when she realized, through close examination of the chronology, trial records, and published and unpublished materials about Maine in the 1680s and 1690s, that key players had experienced trauma in recent Indian wars: a neglected yet essential lens for understanding the crisis.

To aspiring historians who want to blaze new trails, Norton says, “Keep an open mind about sources. Keep an open mind about taking on projects. Keep an open mind about what the possibilities are.” “It’s only when we check our own assumptions and really listen that the voices of the past can speak to us authentically.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast