Why Pandemics Don't End

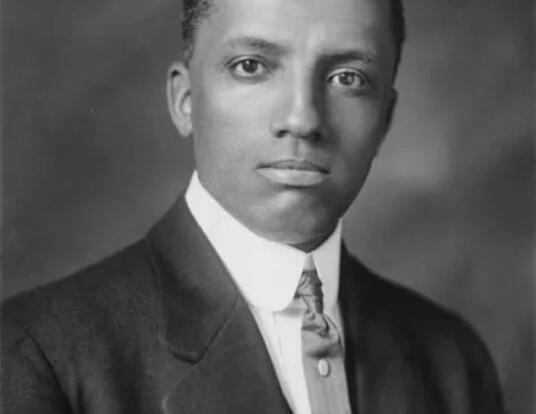

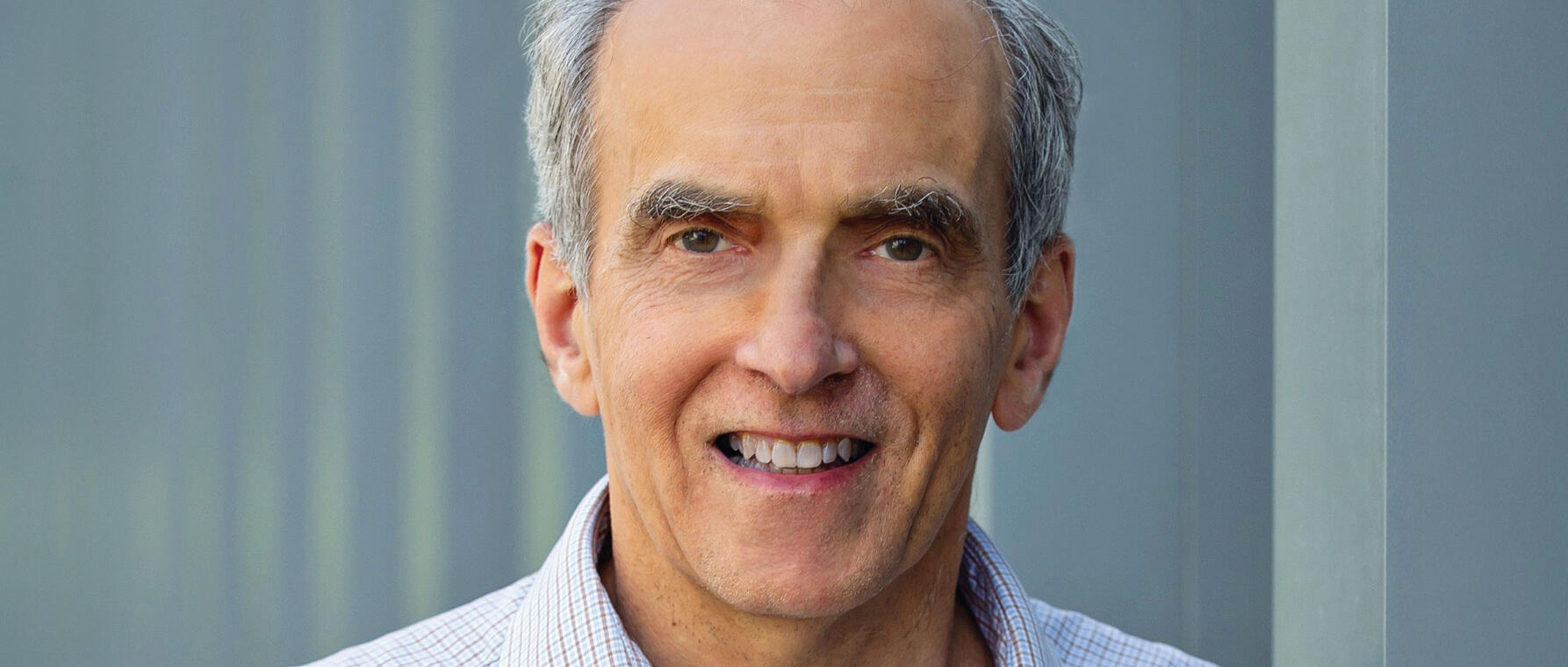

Powel Kazanjian, AM ’02, is a professor of history and internal medicine (infectious diseases) at the University of Michigan and the author of Persisting Pandemics. In the book, he draws on his training in both medicine and the humanities to explore why diseases like syphilis, AIDS, and COVID-19 continue to afflict populations despite major biomedical advances. Kazanjian argues that public health efforts fall short when they fail to address the persistent social, political, and economic inequalities that shape how pandemics unfold and endure.

You begin your book with the myth of the Greek hero Herakles fighting the nine-headed Hydra, cutting off a head only to see two more sprout up in place. Is humanity’s fight against infectious disease that futile?

I chose the Hydra because the ways that the pandemics persist or recur are different than when they first start. Either the pathogens become resistant, or there’s some new issue, like problems with trust in science. These new aspects change the task at hand of eliminating the epidemic that has changed after you first tried to solve it.

Is it really futile to think you can end these epidemics? I think that you can come close to ending some of them. Very few of them have indeed ended, like smallpox. But most often, an epidemic persists, often along socioeconomic divides and in a different sort of capacity. For instance, most people now consider COVID a thing of the past, no longer a problem. But it still kills over 2,000 people a month around the world and can cause severe disease in the elderly or infirm.

You write in the book about the syphilis and AIDS epidemics. For readers who didn’t live through them, what was the impact of these diseases—and of the scientific advances that made them treatable?

Before treatment was available in the 20th century, syphilis was a significant cause of disability and deformity: blindness, strokes, loss of memory, things that aren’t seen that often anymore. Similarly, AIDS almost always progressed to death within three years after diagnosis. They were terrible deaths where people would walk around appearing emaciated and withdrawn. And these were people in the prime of their lives who had productive roles in society as wage earners for families or workers in factories or agriculture and or schools. The impacts of these epidemics went way beyond the individual. They impacted families, communities, education, and nations. Developing countries became weaker because of the loss of economic productivity and of troops able to serve in the military.

Syphilis became treatable early in the 19th century, but particularly so in the 1940s, with the advent of penicillin, a safer drug that was a one-shot cure. The emergence of anti-retrovirals in the 1990s as a treatment for AIDS was seen as almost a miracle. They not only prevented death but also restored people to health. People looked at these drugs euphorically: “We’re going to cure the individual and eliminate the disease from the population.”

You note that despite scientific breakthroughs, these diseases continue to persist. To what extent and why?

I’ve already mentioned COVID. There are presently about eight million new cases of syphilis a year globally. There are 39 million people worldwide living with AIDS, which still kills about 630,000 a year.

One factor is poverty. It can force, for instance, women into commercial sexual activities where they lack the authority to negotiate for condom use, in situations where they get more money if they have condomless sex. Social factors are also important. People can be afraid to be tested still, particularly in conservative societies where they feel they’ll be discriminated against. When they do test positive, some are reluctant to reveal the names of their partners. Government neglect plays a role by not consistently prioritizing funding for elimination programs and cutting funding for programs like USAID (United States Agency for International Development). And there’s public mistrust of medical science. That came through the loudest with COVID. We were never able to reach the necessary amount of vaccine uptake because of this mistrust, which also extended to behaviors like social distancing and masking up.

So, what’s the way out? How can societies combine science with social policy to fight persistent pandemics?

Medical science today is unmatched in terms of treating pathogens, restoring health. But to stop disease, you have to do more than that. It’s important to address longstanding social, economic, and political problems with structural solutions. These include programs to reduce the shame of having a disease so that we can increase the number of people being tested. We’re not going to “solve” poverty, but things like cash transfers could provide sex workers with the capital to invest in less risky businesses. Peer education could also empower them to negotiate for condoms in their work. And we need to resist anti-science appointees in government, as well as the implementation of regressive public health measures, and cutbacks. Sustained funding for science and public health efforts across political administrations is very important.

Finally, there needs to be a change at the individual level. We often think first about how wearing a mask or avoiding crowds interferes with our liberties and our enjoyments, rather than how they protect our society from harm. I think that mindset needs to be interrogated in both conservative and liberal societies.

Banner photo courtesy of the University of Michigan Department of History.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast