A Terrible Freedom

Stewart studies Friedrich Schiller, vulnerability, struggle, and the sublime

If the 18th-century German dramatist and aesthetic philosopher Friedrich Schiller were alive today, he might see in the invasion of Ukraine an instance of life imitating art. Referred to by some as the German Shakespeare, Schiller wrote plays about heroes—and, more often, heroines—who face oppression, enslavement, and war, and yet muster the strength to resist despite their vulnerable position.

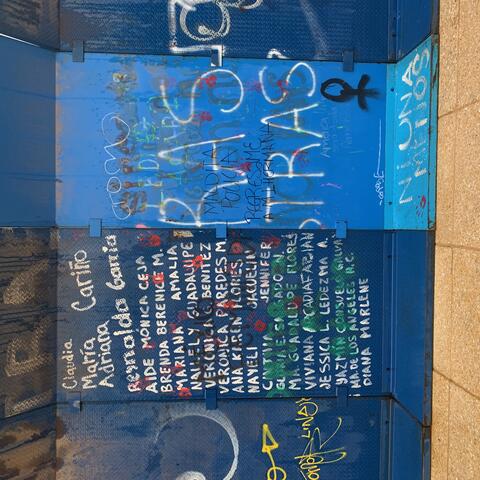

“He’s the hero of the underdog—the poor, the disenfranchised, the oppressed,” says Schiller scholar Rebecca Stewart. “In his tragedies, most often it’s women who choose liberty and resistance over acquiescence or even their own lives. He calls this choice "entsetzliche Freiheit," which means ‘terrible freedom.’”

As a PhD student in German language and literature at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Stewart explores this “terrible freedom.” Looking at Schiller’s art and thought with fresh eyes, she finds in his work a trenchant critique of power and a championing of the marginalized. Moreover, Stewart says that Schiller’s concept of the sublime and its execution in his works is an idea from which the people of Ukraine—and oppressed people everywhere—may draw strength.

The Greatest Struggle

Schiller’s aesthetics engage with the British philosopher Edmund Burke and later the German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s notion of the sublime—the feeling of pleasure mixed with fear that we experience when we encounter something too great to imagine: the vastness of the ocean, the limitlessness of the cosmos. But as early as 1779, when Schiller was nineteen years old, he bound the concept of the sublime to what he calls “the greatest struggle”: the effort to go beyond our most basic instincts.

“Schiller believes the strongest inclination humans have is toward life,” Stewart explains. “We want to survive. We want to be comfortable. Most of all, we want to avoid pain. But we also possess the capacity to resist this inclination for the sake of some higher aim. The sublime is the feeling we get when we observe such an act. It’s the pleasurable recognition of our capacity to overcome our physical limitations.”

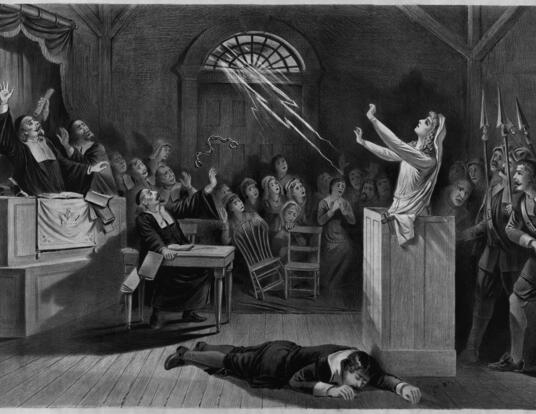

Schiller wanted his audiences to contemplate this capacity after they left the theater. To get them to do so, he portrayed the sublime in his plays as the struggle of the oppressed for liberation.

“Schiller grew up very poor,” Stewart says. “In his dramas, he features the poor, the disenfranchised, and, in one very interesting case, a person of color. But, more often than any of these, it's women who are put in the situation of having to choose between coercion—usually sexual violence—enslavement, and life or liberty, resistance, and death.”

[Schiller’s] sublime is the pleasurable recognition of our capacity to overcome our physical limitations.

—Rebecca Stewart

In Schiller’s The Robbers, for instance, a young woman is threatened with assault after her betrothed is presumed dead, but instead resists, grabs her tormentor’s dagger, and chases him away. In Fiesco's Conspiracy at Genoa, the daughter of the leader of a republican plot is raped by the tyrannical heir of the doge, an act that sparks a rebellion. And in The Maid of Orleans, Johanna D’Arc (a Germanization of Jeanne D’Arc), resists the demand that is made of her––that she submit to a marriage that she does not want or face the threat of assault––from her very first scene until her death at the tragedy’s conclusion.

“Schiller adapts figures of resistance from all periods of history for an audience of his time, 18th-century European society,” Stewart says. “In his era, it is largely the female figure who faces the greatest pressure to fall into line with society's expectations. And when that dramatic figure chooses resistance in Schiller’s plays, she demonstrates the human capacity for freedom. That’s the argument I’m making in my PhD dissertation.”

The Theater of the World

Encouraging resistance among the oppressed was risky business in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The shock of the French Revolution of 1789—and the series of sham trials and executions that followed it—reverberated throughout Europe. French armies occupied German states on the west bank of the Rhine for 20 years beginning in 1793.

“Schiller remains committed to the republican ideals of the revolutionary era,” Stewart says. “But when French forces occupy neighboring states under the banner of freedom, it doesn't look so much like freedom to the people who live there. He writes of the terror that followed the French Revolution and the French Republic’s turn toward imperialism that ‘a moment of such great potential finds itself confronted with an unreceptive generation.’”

For this reason, Stewart says that Schiller would find the tumultuous 21st century very familiar—particularly the invasion of Ukraine. Putin rather than Napoleon is the aggressor in this case. The people of Ukraine are the classic Schillerian underdogs, defending their autonomy in the face of aggression. In the United States, we as observers experience first-hand the playwright’s idea of the sublime.

“The key thing is that the rest of the world is watching this unfold from afar,” Stewart says. “Ukraine’s supporters are not in immediate danger. The theater of the world is what we're observing online, but this is brutal reality for people in Ukraine. Still, it puts us observers in this deep state of awe to witness their bravery.”

What makes the freedom that the Ukrainians are exercising now so terrible, of course, is the cost. Stewart says that Schiller understood the horrible toll of wars and revolutions and did not glorify the “greatest struggle” even as he recognized its sublimity.

“Although he often portrays scenes of wars in his drama and talks about our capacity to overcome the constraints of our physical limitations, Schiller does not glorify violence,” she says. “Rather, he recognizes that it's happening all the time, in particular to the vulnerable. He thinks that self-sacrifice is neither desirable nor sustainable. It's the stuff of tragedy that should ideally be confined to the theater because, as he writes, 'True suffering [...] allows for no aesthetic judgment because it overrides the mind's freedom. Therefore, the terrifying object may not exert its destructive power upon the judging subject…we must not suffer ourselves; rather, we must suffer merely sympathetically.’ However, we live in a less than ideal world, and we see, as Schiller saw, how tragedy spills onto ‘the stage of life.’”

Stewart points to one of Schiller’s most famous works, Letters on the Aesthetic Education of the Individual, in which he argues that, while we strive to pursue concepts like freedom, love, and autonomy, they ought never (but often do) come at the expense of human lives—or as the result of inflicting harm on others. Above all, self-sacrifice must be a choice, freely made.

“Schiller writes that reason, separated from physical conditions, does not care about anything beyond what it determines is right, whatever the cost may be. ‘But,’ he continues, ‘in entirely anthropological terms, where both form and content are of importance and living sensation also has a voice, this difference becomes all the more important.’ The moral law exists to serve humanity, not annihilate it. Since the definitive characteristic of the human being is moral freedom, the moral law does not allow the coercive sacrifice of one's independence and physical well-being for its own sake. Any act of coercion robs the individual of freedom itself.”

Nicole A. Sütterlin, an assistant professor in Harvard’s Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures and one of Stewart’s dissertation readers, says that the PhD student’s scholarship on Schiller has implications for how we think of art, justice, and citizenship today.

“Schiller was a freedom fighter,” Sütterlin says. “For him, ‘aesthetic education’ was key in achieving the ideals of social equality that the French Revolution had promised. Rebecca’s work, by highlighting the importance of women and marginalized communities in Schiller’s texts, shows us how his notion of aesthetic education matters today in our own struggles for democracy.”

“Yeah, right”

Given Schiller’s popularity with 19th-century European composers including Donizetti, Rossini, Tchaikovsky, and, especially, Giuseppe Verdi, it’s not surprising that Stewart has a passion for opera. But she says that her love of music predates that of German literature. Singing, in particular, has been a mainstay for as long as she can remember. She recalls singing in children’s choir and belting Toni Braxton at home with her grandmother when she was a toddler.

“In high school, I sang in the choir and played in the band,” Stewart says. “It was very important to my mother that I got good grades and she knew that the way to motivate me was to tell me I’d have to quit if I got too many low marks. Nothing else would have threatened me, but that did!”

Stewart returned to the Dallas-Fort Worth area to attend college at Texas Christian University (TCU). She began by majoring in vocal performance with a minor in German but flipped the two after classes with some dynamic, supportive German professors. She felt conflicted about whether to pursue her love of language and literature or her dream of being a professional singer. Then she attended a summer German immersion program in New Mexico, where her head was turned again by some brilliant faculty—in particular Professor Jeffrey L. High from California State University, Long Beach (CSULB).

True suffering…allows for no aesthetic judgment because it overrides the mind's freedom. Therefore, the terrifying object may not exert its destructive power upon the judging subject…we must not suffer ourselves; rather, we must suffer merely sympathetically.

—Friedrich Schiller

“I met some of the smartest people I know,” she says. “CSULB was one of the sponsors of the school. Professor High told me I would be a great teacher and invited me to come to California to get my master’s. I did and it completely changed my life. The first class I attended was a Schiller seminar.”

Stewart continued to study voice and perform while at Long Beach. Then one day her advisor suggested she apply to Harvard’s GSAS for her PhD.

“Yeah, right,” she responded, doubtful of her ability to gain admission.

With the professor’s encouragement, Stewart followed through. Now at GSAS, she says that her faculty mentors are as supportive and enthusiastic about her work as those she met at TCU and CSULB. One, William R. Kenan Professor of German and Comparative Literature John T. Hamilton, says that Stewart’s focus on women encourages scholars to reconsider an artist they thought they knew.

“In focusing on relatively minor female characters in Schiller's dramas,” Hamilton says, “Rebecca's work addresses a blatant gap in the scholarship, which tends to reduce the characterizations to mere stereotypes. Her close readings instead demonstrate how these figures play an instrumental role in each drama's unfolding, which calls for revising and reassessing our understanding of Schiller's reflections on aesthetics and politics.”

Just as at TCU and CSULB, music is still a central part of Stewart’s academic and creative life at GSAS. With a secondary field in musicology, she has taught and written about the works of Mozart, Beethoven, and Richard Wagner. As an intern for an LA Opera in 2020, she also co-produced a podcast series to accompany the virtual presentation of all four operas in Wagner’s Ring Cycle, part of the company’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its cancellation of summer programming. She is now working with the Ziering-Conlon Initiative for Recovered Voices at the Colburn School in Los Angeles to research and promote the music of composers who were suppressed due to Nazi policies.

In the winter of 2020, just before the global pandemic forced students off-campus, Stewart worked as both a performer and German diction coach for the Harvard College Opera’s production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. She says that, for sheer joy, the experience may have been the musical high point of her time at GSAS.

“It was maybe the most fun thing I've done at Harvard,” Stewart says, “I played the First Lady. We rehearsed and rehearsed and rehearsed. The show was completely student-run—music and stage direction, sets, everything. I think we blocked the opera in about two weeks over Winter Break and then we had six shows. People loved them.”

Stewart (at left) takes part in the Harvard University Choir’s performance of Judas Maccabaeus by George Frideric Handel.

For Stewart, the study of German literature and opera reinforce one another. She says that studying Schiller’s aesthetic philosophy enables her to better understand the power of works like Verdi’s Don Carlos and Luisa Miller, and Tchaikovsky’s The Maid of Orleans, all based on the German writer’s plays. At the same time, the operas help her better appreciate the ways that Schiller’s dramas deploy his aesthetics and transform the philosophical into the sublime.

“I think in particular of the figure of the Princess Eboli in Don Carlos,” Stewart says. “In her aria, ‘O terrible gift, o cruel gift,’ she expresses her deep pain of regret for having betrayed the queen and Don Carlos. It made her character accessible to me in a way it hadn’t been before. Works like Don Carlos also exemplify Schiller’s belief that art allows us to exercise the imagination in all of its vastness. It enables us to transcend the limitations of physical existence. Philosophy happens in the realm of the conceptual. It becomes real through the art that we make.”

Photos courtesy of Rebecca Stewart

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast