New Research Reveals Super-Black Feathers' Light-Absorbing Properties

A PhD student in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology shares her latest research.

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

What do birds and aerospace engineers have in common? Both have invented incredibly dark, “super-black” surfaces that absorb almost every last bit of light that strikes them.

Of course scientists worked intentionally to devise these materials. It’s evolution that brought this amazing trait about in birds. My co-lead author Teresa Feo, our colleagues Todd A. Harvey and Rick Prum and I recently investigated the super-black feathers in some of the most outlandish animals on earth: the Birds of Paradise.

These are resplendent birds native to Papua New Guinea and surrounding areas. Males are brilliantly colored, with complicated mating dances. Females, who are drab and brown in comparison, carefully inspect the ornaments and dances of males before choosing their mate.

We wanted to know more about these birds’ super-black plumage and how it works. What mechanism do these feathers employ to be so effective at absorbing light?

Fanciest Feathers, Under the Microscope

The Birds of Paradise have evolved many remarkable traits, but none are more mysterious than the males’ velvety black plumage.

This black is so dark that your eyes cannot focus on its surface; it looks like a cave, or a fuzzy black hole in space. Using optical measurements, we found that these feather patches absorb up to 99.95 percent of directly incident light. That’s comparable to human-made very black materials such as solar panels, the lining of space telescopes, and even the “blackest black” material: Vantablack, which absorbs 99.96 percent of light.

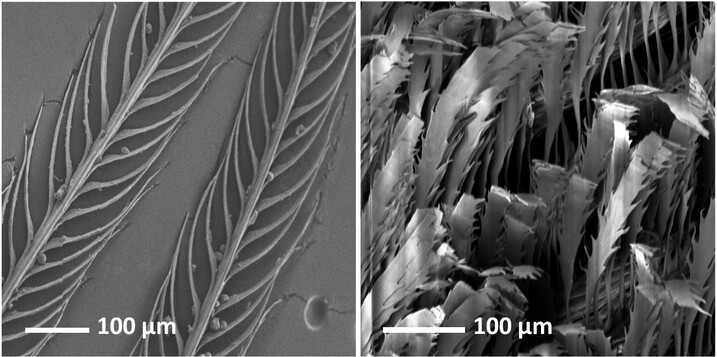

Normal feathers are flat, and look like fractals; when you zoom in using a microscope, each branch of the feather looks like a tiny, flat feather. Under a powerful scanning electron microscope, we were surprised to see that the super-black feathers look like miniature coral reefs, bottle brushes or trees with tightly packed leaves.

These tiny, specially shaped bits stick up to form a jagged, complex surface; together they act as microscopic light traps. When light rays strike these surface microstructures, they repeatedly scatter around the shapes and are absorbed, rather than being reflected back to an observer. It’s an iterative process: Each time a scattering event occurs, a portion of the light is absorbed until it’s almost completely absorbed.

Human-made super-black materials such as “black silicon” also rely on what materials scientists call structural absorption. Like the super-black feathers, their microscopic “light traps” are due to a rough surface that scatters light repeatedly, but the actual surface shapes they use are different. Rather than the feathers’ bottle brush shapes, human engineers designed regularly spaced microscopic cones and pits. With almost no exposed flat surface, these structurally black materials are the opposite of a mirror.

The Birds of Paradise’s super-black feathers are so good at absorbing light that even when we coated them in gold, a shiny metal, they still looked black. That’s because it’s not the inside of the feather making the color via pigment or ordered nanostructures; instead, just as with human-made black silicon, the super black comes from the physical surface structure. Evolution and human ingenuity arrived at the same solution.

Advantages of Super-Black Feathers

But why do these birds have such incredibly dark black patches? What selective advantage caused this trait to evolve? It’s tempting to think that super black somehow helps with camouflage, to keep predators away. In fact, some snakes have super-black scales that mimic shadows between leaves, helping them blend into the forest floor. The snake example illustrates evolution by natural selection – “survival of the fittest.”

But other factors can also influence evolution’s course, including random chance or sexual selection. As my colleague Rick Prum points out in his new book “The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World – and Us,” mate choice is a powerful force driving evolution. In Birds of Paradise, super-black feathers help male birds look more beautiful to a female’s eye.

To understand how, it helps to look at Bird of Paradise mating dances. Males vigorously display their super-black patches to females, making sure that females can’t get a view from the side. This is because these feathers are highly directional, and they look darkest from straight ahead.

And super-black patches always sit around or next to brilliant color patches. A super-black, anti-reflective frame makes nearby colors appear brighter, almost glow. In other words, super black is an evolved optical illusion that relies on the way animal eyes and brains adjust our perceptions based on ambient light.

In the high-stakes game of choosing a mate, a single feather that isn’t quite blue enough could be enough to turn off a female Bird of Paradise. Clearly, female Birds of Paradise prefer males with super-black plumage. As females pick the most impressive males to mate with, those dazzling feather genes are passed on to future generations while the genes of less splendid males, overlooked by females, are not. Sexual selection drove evolution toward super-black plumage.

Evolution is not an orderly, coherent process; evolutionary arms races can produce great innovation. Perhaps these super-black feathers with their unique microscopic structure could eventually inspire better solar panels, or new textiles; super-black butterfly wings already have. Evolution has had millions of years to tinker; we still have much to learn from its solutions.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast