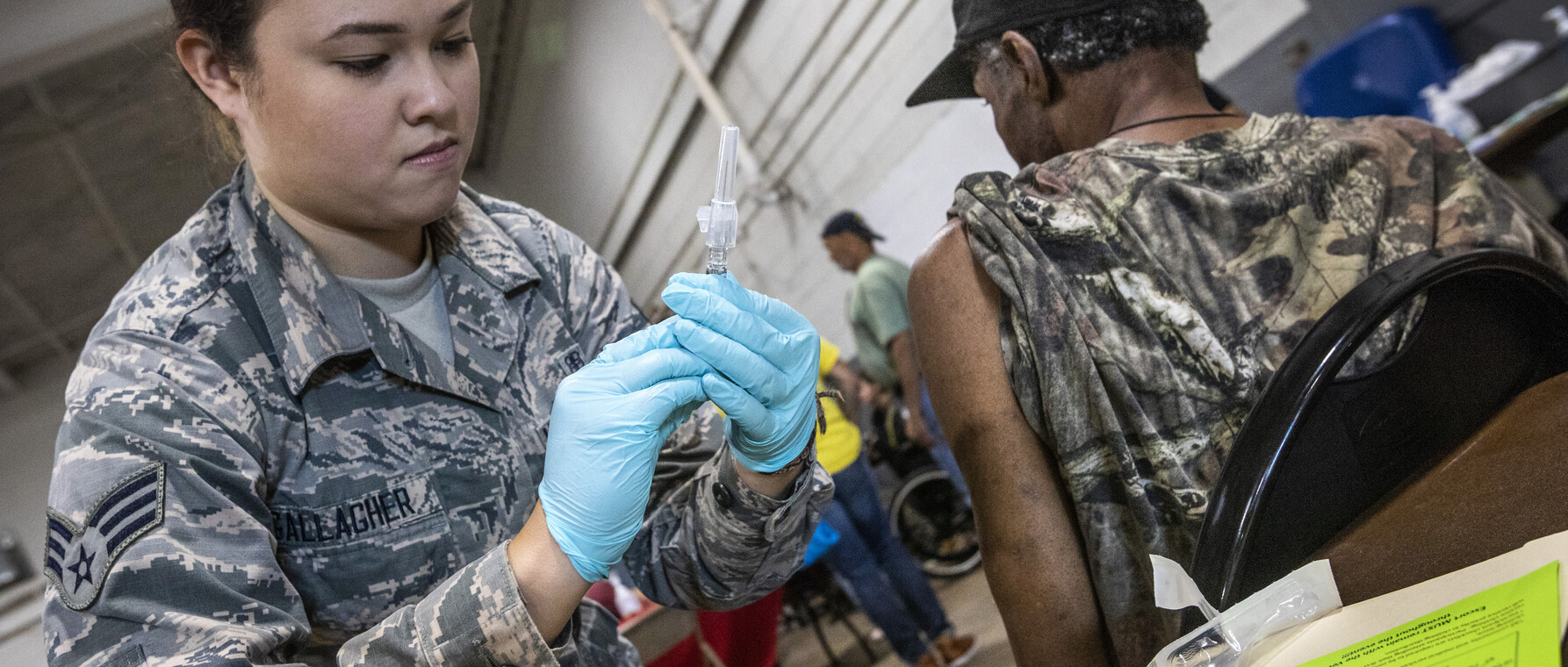

For Healthy Veterans—and a Healthy America

By improving care for wounded warriors, Guerra learns how to improve care for all

As a PhD student at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Steph Guerra was living her dream. She was working to develop new precision therapies for the treatment of cancer. Her mentor was Harvard Medical School Professor Karen Cichowski, co-director of Harvard’s Cancer Cell Biology Program and a leader in her field. The lab was based at one of the nation’s top hospitals—Boston’s Brigham and Women’s. What more could a student in Biomedical and Biological Sciences want?

Still, something wasn’t right. Guerra knew that the treatments she was helping to develop would be an important advance in medical technology. They would be costly, though, and not widely available. Who would actually get them?

“I was working at my lab bench,” she remembers. “I thought, ‘Precision medicine can save a lot of lives.’ But I wanted to make sure that my work didn’t worsen the health disparities that already exist. I didn’t want it only to reach people who already got the best care in the world and not anyone else.”

Today, Guerra, PhD ’18 works at the largest and most accessible integrated health system in the country—the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). As an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology Policy Fellow in the Office of Research and Development (ORD), she leads projects designed to improve health care for members of vulnerable populations whose financial resources are sparse. With the knowledge and experience she gains, she hopes to help make care better for all Americans.

A Crash Course in Real-World Impact

After her epiphany at the Cichowski Lab, Guerra decided that she wanted to focus on health policy—specifically, how to make emerging treatments available to a wide swath of the population. She landed at the VHA because, she says, there is no better place to learn about increasing access to treatment.

“Veterans have lots of comorbidities and pre-existing conditions,” she explains. “They live in places where it’s hard to get access to care. At the VHA, I’ve learned so much about how to get treatment to vulnerable populations. It’s been a crash course in real-world impact.”

From the administration’s central office in Washington, DC, Guerra and her colleagues work with VHA hospitals around the country, providing data and collaborating with them to develop new policies. She says that one of the things she most admires about the system is the way that researchers connect with clinicians in the field.

“A VHA national program office will come to us,” she says. “They’ll tell us where they see a problem and ask for research that can help them understand it. It’s our job to give them that support.”

One big problem that Guerra and her colleagues address is the opioid epidemic. In the 1990s, clinicians began to understand the importance of treating pain as a fifth vital sign—along with temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure. Veterans as a group experience a great deal of physical pain from combat injuries. Opioid use rose—sometimes because of good faith efforts to treat pain, sometimes because pharmaceutical companies aggressively promoted the drugs, sometimes because illicit drug traffickers targeted rural communities. Whatever the constellation of causes, the impact was devastating. From 1999 to 2018, opioid overdoses claimed the lives of nearly 450,000 Americans. In 2016, that translated to 13.3 deaths from overdose per 100,000 people. The rate of death for veterans was about 50 percent higher.

“A ‘perfect storm’ gathered in the late ’90s,” she says. “Patients’ physical pain needed treatment, but their emotional pain did too. Prescriptions increased without a clear understanding of how all those factors interacted and what the consequences would be. And yes, the pharmaceutical industry pushed the use of opioids. It’s a large-scale problem and the VHA is doing a lot to reverse it.”

At ORD, Guerra solicits proposals from VHA researchers studying the problem of opioid safety and dependency. What’s unique about these projects is that the investigators work closely with stakeholders, from clinicians in the field who know where the information gaps are to the veterans themselves who are invited to consult on projects. The result is research that addresses the challenges that VHA health care professionals—and their patients—face every day.

“We’re concerned with impact in the real world, not just ‘impact factors,’” Guerra says. “If you don’t collaborate closely with the end-user, then it’s less likely that the work will address the problem. Our VA researchers work closely with partners who will use the evidence we generate to create better clinical policies and programs.”

RIVR Runs Through It

Guerra still works on cancer care at the VHA, but from a different angle than when she was in the lab. She’s trying to revitalize the cancer data “ecosystem” that shapes the kind of treatment patients receive. By analyzing information from the Administration’s massive database, ORD can help clinicians understand the mutations that cause cancers to grow, match tumors with the treatments that are most likely to be effective, and connect patients with clinical trials.

“Every single tumor is different,” Guerra says. “Precision medicine allows us to tailor treatment to the patient. My job is to bring together the people at the cancer registries with researchers who are developing tools to make cancer data curation and quality more efficient and better at the VHA. We want the VHA to be the best place for them to get cancer care.”

Beyond her work with precision oncology and the opioids epidemic, Guerra has also managed a new research funding mechanism at her office. Through the Research to Impact Veterans (RIVR) program, Guerra is working to bring ORD’s approach of funding research impacts to new areas of research and practice. The five-year initiative provides funding for projects that spread evidence-based medicine throughout the VHA, align the goals of their research with those of clinicians and patients, develop new tools that enable providers to deliver better care, and analyze data from across the VHA system for insights that will lead to more effective treatment.

At the VHA, I’ve learned so much about how to get treatment to vulnerable populations. It’s been a crash course in real-world impact.

“We support projects that would usually have a hard time getting funded,” she says. “For instance, you might have a big research study that generated new information about evidence-based medicine. But only a small part of that study might deal with how to implement those findings. With the RIVR program, implementation is the study—and VHA hospitals around the country will use the guides, tool kits, and data dashboards it generates.”

The RIVR program is only a year old, but it’s already funded 20 projects that have developed close collaborations with 35 VHA national program offices and 16 VHA regional offices around the country. Moreover, the flexibility of the funding enables the researchers to pivot as the circumstances around them change.

“During COVID-19,” Guerra says, “many RIVR projects shifted their priorities to understand their project in the context of the virus. That generated important new research on telehealth and pain management, to name only one benefit.”

It’s only been a couple of years since Guerra graduated from GSAS, so it’s hard for her to know where her career path will lead her. She says that she’s “in love” with health policy and that she’d like to continue working in government. Wherever she goes, she will take her passion for serving vulnerable communities and reducing suffering with her.

“I’m still figuring out what my niche is,” she says, “but I want to be on the front lines. I want to take the lessons I’ve learned at the VHA and spread them wider. There are so many ways to help and the VHA has done a lot that the country can learn from.”

Photo courtesy of Steph Guerra, New Jersey National Guard photo by Mark C. Olsen

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast Stitcher