Epic Grief

How decorum—as depicted in classical literature—can help us understand how people mourn

PhD candidate Susannah Wright chose grief in Latin epic poetry as the focus of her doctoral research at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. With hundreds of thousands dead and many more sickened, loss and mourning had become prominent themes in the private and public lives of citizens in the US and around the world.

“I found myself struck in a new way by moments of grief in these epic texts,” Wright says. “Part of the reason these works continue to capture readers’ attention today is that they have an incredibly humane way of showing what people do when a loved one is lost.”

In her dissertation, “Sunt Lacrimae Rerum: Decorum and Grief in Ancient and Medieval Latin Epic,” Wright explores how considerations of appropriateness regulate representations of grief in Latin epic texts from antiquity to the Middle Ages. In so doing, she sheds new light on how rituals and rules of conduct enable us to find our way through life’s darkest hours.

An Early Love of Epic

Wright’s interest in the classics was first sparked in third grade when she had to dress up as a Greek goddess and give a presentation to her class. She was assigned Athena—the goddess of wisdom—so she came to school adorned with a helmet, spear, and shield, and a little owl she carried on her shoulder.

“I enjoyed that project so much that I ended up getting involved in the mythology club that the middle school Latin teacher was leading at the time,” Wright says. “We would all stay after school on Thursdays to hear stories from the Odyssey. I found them absolutely enchanting.”

As Wright progressed through primary and secondary school, her newfound interest in ancient mythology motivated her to begin studying Latin in earnest and to enter competitions as soon as she could. She went on to earn her bachelor’s degree in classics and medieval studies from Rice University before deciding to attend the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) for her PhD in classical philology.

“I’ve always been interested in a range of ancient texts,” Wright says, “but ever since those first experiences with the Odyssey, I have been particularly gripped by epic poetry—so I knew I wanted my dissertation project to be something that dealt with epic through time.”

Epic texts—monumental poetic works narrating the exploits of larger-than-life figures—have long been at the center of classics curricula; the Greek Iliad and Odyssey and the Latin Aeneid are the best-known examples. But, as Wright’s research underscores, the tradition did not end here. For well over a millennium after the Aeneid was circulated, for instance, poets continued to compose Latin epic texts that engaged closely with earlier works.

Most studies of epic, Wright notes, focus on one text or a relatively small number. Hers, however, attempts to emphasize the continuity of the genre by grappling with a larger group. Beginning with the foundational Greek epics of Homer and Apollonius, Wright’s dissertation moves chronologically from major Latin works like Virgil’s Aeneid to lesser-known texts like Joseph of Exeter’s De Bello Troiano and Walter of Châtillon’s Alexandreis, both from the 12th century CE. She estimates the size of her corpus at roughly 30,000 lines of Greek verse and 75,000 lines of Latin, from which she has identified the most prominent moments of loss and mourning as her focus.

Part of the reason these works continue to capture readers’ attention today is that they have an incredibly humane way of showing what people do when a loved one is lost.

– Susannah Wright

Grief Gone Wild

Once grief in epic poetry became the clear topic for her dissertation, Wright began to formulate the questions about it that interested her the most—and for which she believed there hadn’t yet been adequate answers in the academic literature. Within the world of these texts, she wondered: Is there a right way to grieve? Do losses bind people together or tear them apart? To what extent are expressions of grief governed by behavioral, social, or religious factors? Are such outpourings of emotion presented as a force for human connection and social stability, or exactly the opposite? “Though these questions all have great relevance in a modern world still reeling from the devastating losses and ongoing challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, they are by no means new,” Wright says.

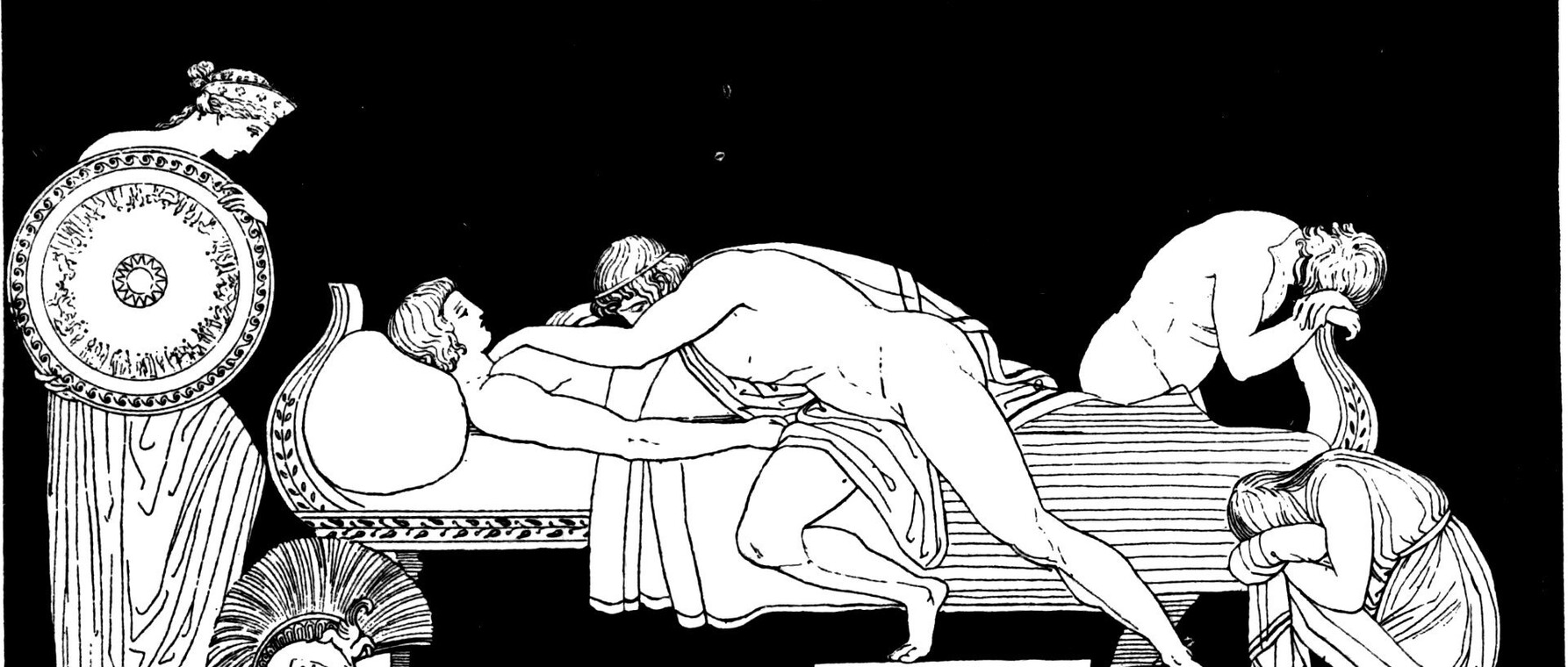

Wright emphasizes that the Greeks and Romans had sophisticated ideas of decorum that operated in fields of all types, from rhetoric and literary criticism to philosophy and the visual arts. Building on previous studies, her project brings together various understandings of appropriateness to develop a comprehensive sense of the concept that can then be applied to moments of grief in epic.

“I think ideas of appropriateness have a lot to tell us about how grief is represented in epic texts, and where they draw the line of what is acceptable,” Wright says. “The emphasis on propriety and moderation found in many areas of Greco-Roman thought brings with it a deep sense that there’s something dangerous about grief gone wild.”

As an example, Wright points to Achilles, hero of the Iliad, who becomes inconsolably upset after his companion Patroclus is killed in battle by the Trojan champion Hector.

“But by the time we get to the Roman epics, Virgil in particular has built up this new heroic ideal based on subordinating private feelings to public responsibility,” Wright says. “So, when Aeneas goes through comparable losses in the Aeneid, he can’t grieve for them in the same unbridled way as Achilles does, because he sees himself as having a responsibility to act differently. His sense of duty—which I argue is rooted in decorum—overrides his ability to mourn openly.”

Wright cites the mourning behavior of the epic protagonist as one of many decorum-related threads she has identified in the tradition, with others involving the grief of female characters, of parents, and even of the gods.

"I’ve located quite a few cases where poets explicitly use the language of propriety to signal whether a certain mode of displaying grief is appropriate,” Wright says, "and those moments are always exciting to find. But, of course, things are often considerably more subtle than that—which makes the work of interpreting them all the more intriguing.”

Emotion at a Time of Loss

An approach that Wright has found particularly useful in her analysis is the application of terminology and understandings about how humans grieve from contemporary psychology. At the same time, Wright realizes that it’s important to exercise caution when looking through modern eyes at the experiences and literary works of people who lived in ancient times.

“For this project, my own engagement with recent scholarship on bereavement generally focuses on the areas that seem most likely to help us, as modern readers, understand the experience of grief that is being depicted in a given epic situation,” Wright says. “Things like classifications of the different types of grief, explanations of why humans grieve, and analyses of what it means for us to do so can all be helpful for this purpose,” she adds, “because they touch on aspects of bereavement that probably have more to do with the experience of being a human than with the specific age in which we live.”

To that point, Wright believes that her work speaks to the question many people still have today about whether there is a right way to grieve or a proper way to speak to someone who's grieving.

“The answer to those questions is fundamentally relative,” Wright says. “Although most people in the modern world would not be likely to proclaim that there’s a single correct way to grieve, there are still these ideas of right behavior that people often have in their heads based on their own cultural values and religious backgrounds.”

A Timeless Human Experience

Wright’s dissertation advisor James Loeb Professor of the Classics Kathleen Coleman adds that in our modern age, in which self-expression and a disregard for convention are at odds with ritual and formal constraints, people can nevertheless derive great comfort from the rituals of funeral services and burial rites.

“Examining the limits put on grief in literature from ancient and medieval Rome can help us understand our own reactions and feel less socially isolated,” Coleman says. “It also reveals the extraordinary sensitivity with which a poet like Virgil captured the range of human emotion in times of great personal loss.”

Coleman notes that epic poetry is the most ancient and most studied of the literary genres from the Greco-Roman world, but that no one has yet investigated how the notion of decorum shapes the treatment of grief in those texts.

Examining the limits put on grief in literature from ancient and medieval Rome can help us understand our own reactions and feel less socially isolated.

– Professor Kathleen Coleman

“There seems to be something fundamental in the human psyche that needs to channel grief into forms deemed acceptable by society,” Coleman says, “and Susannah’s dissertation shows how ancient these impulses are and emphasizes the emotional continuity between the Greco-Roman past and today’s world.”

Ultimately, Wright hopes that her work will help us understand the ways in which people can reclaim some degree of agency for themselves in the midst of the inevitable vicissitudes of life.

“When there’s a loss, so much can feel like it’s out of our control,” Wright says, “but the connections between decorum and grief in these ancient texts are powerful reminders that people struggled even then to navigate moments of sorrow. Grief is, in a certain sense, the most timeless human experience there is.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast