Empowering Appalachia

How a community-based approach can encourage greater political participation in communities devastated by industrial decline

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

Elizabeth Thom traces her interest in politics back to her hometown of Philadelphia. Growing up in the suburbs and then moving into the city to study at the University of Pennsylvania, she saw a microcosm of the regional differences that drive national politics.

“You have big cities, and also a lot of rural agricultural areas, as well as old manufacturing areas, and coal-producing regions, too,” Thom says, and she observed how the range of economic conditions, cultures, and social structures in these places led to marked differences in political behaviors.

Thom, who graduates this May with a PhD in government and social policy, carries that interest in regional politics into her work on responses to policy initiatives in Central Appalachia. Her research identifies trends in political participation at the local level, linking political engagement to the impact of government social programs––and proposing ways policymakers might better empower communities challenged by drastic economic and industrial change.

Social Policy and Civic Participation

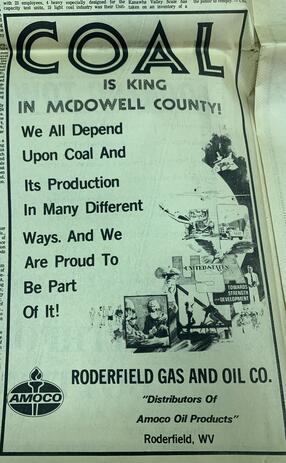

Thom looks at communities that have faced economic hardship following the clean energy transition and the decline of the coal industry. “Broadly, I study the politics of industrial decline,” she explains, “and the ways that government interventions and policies intersect with economic conditions in these areas. I want to understand how they can reshape communities and either help or hinder people’s sense of relationships to one another and to government.”

A branch of political science known as policy feedback theory, Thom says, considers how benefiting from a social program can impact a person’s civic participation and feelings of political efficacy. According to existing models in policy feedback theory, Thom explains, “if you face a circumstance that makes you eligible for a social program, you receive a benefit, and through that process of becoming a beneficiary, you tend to become more invested in the program and the politics around it, and more willing to engage.”

A classic example of this phenomenon, Thom says, involves recipients of Social Security retirement benefits; political scientists have observed high levels of voter turnout and political engagement among senior citizens because of the direct financial benefit they receive from Social Security, leading them to feel a personal connection to government and, in turn, motivation for political advocacy and action to support the social programs that benefit them.

However, in the Central Appalachian communities that Thom studies, where high proportions of the population benefit from government social programs, “we see lower levels of political participation, and lower levels of political efficacy, which runs contrary to our ideas about some of the programs and their designs, which ought to be boosting political participation,” she says.

In this context, Central Appalachia is the center of a political puzzle. While successful recipients of government assistance generally tend to participate in politics more frequently, many Central Appalachian communities have experienced the exact opposite effect, showing decreased participation even though they have some of the highest proportions of individuals receiving social welfare benefits.

To account for these unexpected patterns, Thom proposes a new way of studying the local dynamics of communities and regions in Central Appalachia, rather than focusing on individuals. “Political science has a lot of theories about this at the individual level,” Thom explains, “but my contribution is to think through the community-level mechanisms that policy intervention can generate. I try to offer explanations through community-level factors that can help us understand why certain social programs don’t produce the expected political participation outcomes in these cases.”

Thom employs a mixed-methods research approach, combining quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Professor Theda Skocpol, Thom’s dissertation advisor and Harvard’s Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology, remarks that the student “is willing to use many kinds of evidence––statistics, interviews, community ethnography––and she writes with grace and clarity,” tackling “compelling questions whose answers matter in the larger world beyond universities, as well as to fellow scholars.”

Using data from government records, Thom has developed methods of tracking county-level trends over time, revealing patterns in participation in both social programs and political activity. This quantitative work led Thom to specific areas of Central Appalachia, where she conducted several months of ethnographic fieldwork and archival research in order to learn from residents’ experiences of life in an economically transforming region. “There are things that Big Data can’t tell me,” Thom reflects, “so it was important to talk directly to people about their experiences over time, and to do archival work there with local records and newspapers that can’t be accessed digitally.”

Barriers to Benefits

One particularly relevant social program that Thom has studied in her dissertation project is Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), which provides monthly financial assistance to individuals with disabling conditions that impair their ability to work. “I study places with high concentrations of people receiving Social Security Disability Insurance,” Thom explains, “which is a contributory social insurance program––that’s a technical way of saying that part of every worker’s paycheck contributes into the fund, and if an individual faces some sort of debilitating condition, this becomes an available option for support.” In Central Appalachia’s coal-producing regions, where the labor involved in mining is very physically demanding, there have been very high concentrations of people requesting and receiving SSDI benefits as a result of becoming disabled earlier in life due to their work.

Even though we typically expect social programs to promote better political engagement, Thom says, “there are certain policy features of SSDI that, I argue, actually make it less likely for people to engage. One of them is that it’s generally universally available––there is a sense that we all contribute into the SSDI fund––but ultimately, there is a pretty rigorous application process to actually get SSDI benefits.”

In communities with high concentrations of SSDI applicants and beneficiaries, Thom explains, “there are a lot of people who either rely on SSDI, or have experience applying for it but not getting it: in recent years, the successful application rate has been low enough that around two-thirds of applications are rejected.” Given the exceptionally high percentage of individuals involved in the SSDI application process in these communities, personal stories about unsuccessful or unduly difficult SSDI benefit applications tend to spread widely through social networks there, leading citizens to disengage from political participation based on what they observe as instances of the government failing to support people like them: their own community members in need.

“The negative experiences with applying for government benefits exacerbate the declining economic conditions that come with the coal industry’s decline in Central Appalachia,” Thom explains, “and people experience a kind of double whammy––income losses from declining industries and a hard time accessing supports from social programs––which leaves them feeling forgotten about or abandoned by both industry and government. Ultimately, those experiences lead to disengagement and low levels of political efficacy.”

People experience a kind of double whammy—income losses from declining industries and a hard time accessing supports from social programs—which leaves them feeling forgotten about or abandoned by both industry and government. Ultimately, those experiences lead to disengagement and low levels of political efficacy.

—Elizabeth Thom

And thus, the theoretically “surprising” result: even in communities with high concentrations of SSDI beneficiaries, the existing policies around the implementation of SSDI have actually had the effect of decreasing political engagement. “This includes overall patterns of participation, including voting as well as other kinds of engagement in civic life: running for local offices, contributing to political campaigns, participating in local civic groups like fraternal organizations, or other local clubs,” Thom explains, “and even church membership can be considered a kind of political participation––I take a broad understanding of what political participation could be and look at trends in all these possible areas, beyond just whether people show up at the voting booth on Election Day.”

Empowering Resilient Communities

In addition to identifying and explaining existing trends and problems, Thom’s doctoral research also proposes strategies for new paths forward. “In Appalachia, these communities have literally provided the fuel that drove industrialization, war efforts, and the creation of the US as we know it today,” Thom notes, “and I think a lot more can be done to support these folks as we continue to move forward with new economic arrangements.”

The strategies that Thom proposes focus on community-based initiatives. This approach stands in contrast to typical models for social programs, which are usually structured around individuals as recipients of benefits. “The health of our democracy is contingent upon the health of the social fabric, the health of the social structures that make up community life,” Thom says, “and we can think through policymaking in a more holistic way, thinking not just through individuals but also through communities. This is the broader impact that I hope my work has.”

As examples of community-oriented social policy, Thom cites the Great Society programs of the mid-1960s and the Biden administration’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act as models for social programs built around empowering entire communities and regions by addressing economic conditions on these larger scales. Future policymakers, Thom suggests, could aim to support an entire area’s economy with a social program, rather than directing benefits to individual workers or industries. “Locating new industries in economically struggling areas––or co-locating those industries with worker development and training programs––can also help achieve economic revitalization in an area, while bringing the people in the affected communities along with the process,” Thom explains. New social programs could also involve local residents in a “policy council” that empowers the community to influence the new program, and to become better educated about politics and government in the process.

In a time of massive, fast-moving economic change, Thom hopes her research in Central Appalachia can inspire and impact researchers, policymakers, and communities both within and beyond the region. “We’re in a moment where a lot of industries are changing,” she observes, “including in relation to artificial intelligence. We’re on the cusp of a lot of major change––and we would do well to learn from the experiences of people who have been through this kind of change already.”

Locating new industries in economically struggling areas––or co-locating those industries with worker development and training programs––can help achieve economic revitalization in an area, while bringing the people in the affected communities along with the process.

—Elizabeth Thom

Following her 2025 graduation from Harvard, Thom plans to continue her academic career as an assistant professor in political science and environmental policy & culture at Northwestern University, where her work on the political impacts of economic, industrial, and environmental change will inform further research and teaching in these areas.

One of her most impactful findings from her research thus far, Thom says, has to do with the resilience of the communities she has worked with. “Through the community support networks that build up, people find ways to survive and community bonds endure,” she says. Ultimately, Thom explains, her work approaches politics from a place-based perspective––which she views as a way to connect to anyone she speaks with, in her various roles as a scholar, educator, public commentator, and citizen. “Everyone brings with them personal experiences of place, stories from their communities, and how these backgrounds inform their own thinking,” she says, “and the value in getting away from my computer and out into the world to talk to people has been like a north star guiding my research.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast