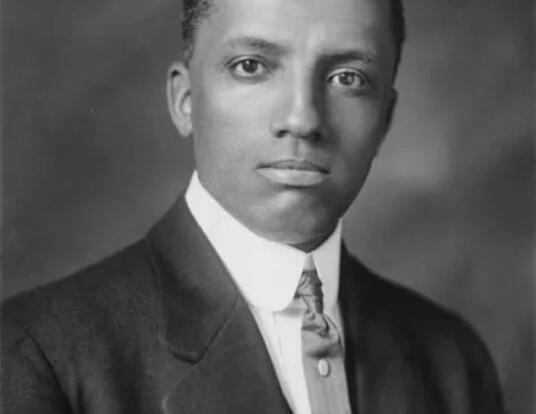

Analyzing Anesthesia

Emery Brown, PhD ’88

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

Emery Brown is the Warren M. Zapol Professor of Anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and also sits on the faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He discusses his research on statistics and anesthesia, being at the forefront of the computational revolution, and “stumbling” on circadian rhythms as a student at Harvard Griffin GSAS.

An Autopilot for Anesthesiologists

I am an anesthesiologist, and I also have a PhD in statistics. My research has two components. One is the development of new statistical techniques to analyze neuroscience data, and the other is using those techniques to study anesthesia and decipher how those drugs work.

When an anesthesiologist gives you anesthesia, they place you in this profound state in which the body is quite inactivated. When you’re conscious, your brain waves are normally at a high frequency with a small amplitude. Anesthesia changes those oscillations to a low frequency with a large amplitude. At those frequencies, your brain can’t communicate, and you lose consciousness. By looking at the patterns in an electroencephalogram (EEG), an anesthesiologist can modulate the dosage of a patient’s drugs and find the amount of anesthesia that someone can best tolerate while remaining unconscious to the painful stimuli of surgery. This is particularly important for the treatment of older patients whose brains are maybe a little more frail and who could suffer cognitive problems after an operation.

To help anesthesiologists find this balance, my colleagues and I developed closed-loop control systems to read the EEG in real-time and, based on that feedback, dose the patient accordingly. We hope that they will act as an autopilot mechanism for anesthesiologists, enabling doctors to monitor the patient more closely to precisely control the level of anesthetic. The systems have been successfully tested in non-human primates. Our next step is to receive permission for human testing.

A Very Good Idea

I was an undergraduate at Harvard College, and I majored in applied mathematics, specifically statistics. I was interested in medicine and statistics, so I wrote my thesis on studying outcomes from surgery. After I graduated, I wanted to go to medical school and also get a PhD in statistics, but when I was interviewing with MD-PhD programs across the country, people were confused. It was 1977 or 1978, before the revolution in computation and AI that we’ve seen in recent years, and many thought it was weird to study statistics alongside an MD. Some programs asked me to write more application essays about why I wanted to study statistics—basically, to explain myself. When I applied to the MD-PhD program at Harvard, I told my undergraduate advisor, the late Professor Fred Mosteller, that I wanted to study statistics. He said he thought it was a very good idea, so I went to Harvard.

People did not think seriously about statistics in medicine at that time and just built ad hoc procedures. When I applied statistical principles to our methods, they worked better. For example, one problem I worked on involved recording neural activity in rats. If you focus on their hippocampus, which is responsible for short-term memory, you’ll record these neurons called play cells. These fire only in certain areas as an animal runs around its environment. It’s like they’re making a mental map of where they are. If you record that activity long enough, you could answer the question of where the animal is based on that mental map. I built a very principled technique for doing this and it got a lot of attention.

Interesting Problems

When I first joined the program as a graduate student, I met with Professor Peter Huber who developed the field of robust statistical techniques. I wanted to work in that field, but he told me that he was tired of robust statistics. He advised me to find interesting problems. If I did, he said he would work with me.

That is how I stumbled upon circadian rhythms, which became the foundation of my dissertation. Fortunately, Huber found my questions interesting, and he became my advisor. I had carte blanche to go and start attacking problems under his guidance. I learned a lot and I think the field benefited.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast