How Military Occupation Sparked the American Revolution

Historian and former presidential adviser Ted Widmer discusses the use of state power in the 18th century—and today

Armed troops in the streets of an American city. A leader in a faraway capital determined to exercise his power over the people there. Screams of protest from residents who demand the force's withdrawal. Resistance, violence, and tragic deaths. These are the elements that made Boston the cauldron of the American Revolution in the 1770s. Are they playing out again in the United States today? And what are the limits of looking to history to better understand the current moment?

Joining us to consider these and other questions about the use of state power then and now is the historian and author Ted Widmer. The Distinguished Lecturer at the Macaulay Honors College of the City University of New York, Widmer is the writer and editor of numerous books including Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington, winner of the prize for best book of the year from the Lincoln Forum, and the inaugural prize for best book from the Society of Presidential Descendants, among other awards. From 1997 to 2001, Widmer served as speechwriter and senior advisor to President Bill Clinton, and senior adviser to Secretary of State Hilary Clinton from 2012 to 2014. This year, Ted Widmer is the W. E. B. Du Bois Fellow at Harvard's Hutchins Center for African and African American Research. His piece, "Boston in the 1770s. Minneapolis in 2026." appeared in the Ideas section of the January 27 edition of the Boston Globe.

You and I are sitting in Cambridge, Massachusetts right now. We don't think of the Boston area as the site of a military occupation. (That might be different if we were indigenous people.) But of course, it was—twice, actually, between 1768 and 1770, and from 1774 to 1776. What precipitated those occupations, and what were the goals of the British government in sending troops to Boston?

This was the red-hot center of resistance to British imperial overreach in the 1760s and 1770s. The British had paid a lot of money to win a war. And it was a war that Americans and English fought alongside each other. We call it the French and Indian War. The British call it the Seven Years’ War, and it resulted in a victory over the French.

It was fought around New England and Canada, and so everyone was happy. But then the British realized they'd spent a lot of money winning the war. And it had benefited these New Englanders. So they wanted to extract some money from them. And they began to do that by taxing them. And taxes had been around a long time, but they didn't settle well with New Englanders, who had a very keen sense of their political rights for reasons in their own history, going back to the founding of New England, when they were largely governing themselves for a long time.

But as Parliament was trying new things, Parliament wasn't explaining its logic very well. New Englanders were trying hard to explain why they didn't feel like paying taxes if they were not represented in Parliament, and the struggle kept getting tenser year to year. There were small acts of violence around Boston in the mid-1760s. A new set of taxes called the Townshend Acts is created in 1767, and Boston is just really unhappy.

So the British, for the first of two times, send thousands of redcoats. New Englanders called them “lobsterbacks.” But British regulars are brought here and occupied the city of Boston. And it's a big mistake. It just drives the wedge in even deeper.

Why did the colonists feel so strongly that Parliament had no right to tax them?

Well, they knew what representative government was. They had local representative government here in Boston and Cambridge, and nearly every Massachusetts town had a town meeting. But there's the General Court of Massachusetts. So they knew very well what it was to be assessed and to pay a tax and to be able to complain about it to your local representative.

And they had none of those feelings when Parliament starts taxing them from thousands of miles away. Parliament has this argument that they are virtually represented—that all these people in London are thinking of them. But that wasn't real representation. That was the nub of the argument, and the New Englanders . . . they just didn't buy this weak argument.

Parliament had moved the ball around and New Englanders were good at following the ball, and they didn't like where this was all heading. It was heading toward a much more authoritarian government. And as these two occupations of Boston took place, it just made everything worse, because then you get into other kinds of violations of civil and political rights, including having a British soldier come into your house without a warrant—[something] we’re thinking about a lot right now in 2026.

And so, as this struggle is happening between Americans and the English, the New Englanders were able to cite ancient English law very effectively. And the British had worked out over centuries a common law. Some of it is very ancient, like Magna Carta, but a lot of it they worked out in the 17th century, and kings did not have unlimited power.

And it was important to have a legal process, to have trial by jury, habeas corpus—all of these sacred legal rights that we think of as sacred American legal rights. Most of them go back to an older English law.

As these two occupations of Boston took place . . . you get into other kinds of violations of civil and political rights, including having a British soldier come into your house without a warrant—[something] we’re thinking about a lot right now in 2026.

Fair enough, but my understanding of what British government was like in the mid to late 18th century is that it was fairly aristocratic and even authoritarian. The king had a lot more power than he does today. So why did the colonists feel like they could still call themselves British citizens, but somehow they have the right to greater representation than they probably would have had in Great Britain?

I don't think all Americans felt the same level of being aggrieved. New Englanders were different. They were very focused on their political rights. They had achieved a pretty high level of independence in their political affairs [in North America], and they knew where they came from. They came from a group of people who had left England in the 1620s and 1630s and in the decades that followed, because they felt already England was getting too authoritarian. That struggle was more religious than political, but they remembered it very well. And one of the things that the Puritans hated was royal soldiers coming into houses. And usually they were looking for a Bible, because there was a kind of a Bible the Puritans liked that was different from the Church of England Bible. And that's a very personal violation of your space. So they just remembered that.

They loved their homes. They loved to quote back to English authorities that famous legal phrase, “a man's home is his castle.” That comes from around the time of the Puritans coming over. And today, the Fourth Amendment—a very important amendment about preventing unreasonable search and seizure—you know, it's only going to get more important with AI and every police officer needing to seize cell phones. That amendment can be traced back to an incident in Boston in 1766 when there was a kind of a riot in the streets of the North End when a man refused to open up his house to an English inspector because he didn't have the right kind of warrant. So, [the colonists] were very focused on the right to privacy inside your home.

You were mentioning soldiers. Today, the US spends more on its military than any other country in the world. We've got over a million active-duty personnel. What was the attitude toward large standing armies in Britain and in the colonies just before the Revolutionary War?

Well, they were unpopular both in England and in the colonies. And again, to go back 100 years earlier, in the time of the religious arguments and the English Civil War, and even a little before that, there's a feeling that standing armies are a terrible thing for any self-respecting quasi-democratic society—that they inevitably encroach on people's rights and go into their homes, as I was just saying.

And so the New Englanders remembered that very well. And when the first occupying force of British comes over to Boston in 1768, they're really unhappy. And it doesn't go well from the beginning. There are constant little standoffs. New Englanders don't like being asked for their papers by strangers, and these were not the best-trained troops either.

A lot of them were impressed into the British Army, and so they weren't very sensitive to local needs. And even, on the contrary, probably enjoyed lording it over local people who were powerless to push back. Except over time, they weren't so powerless because little vigilante groups like the Sons of Liberty went around making life uncomfortable for the soldiers.

For two very long years, a big contingent of British soldiers was in the middle of the city of Boston, which was a pretty small city back then. It was a city connected to the land by only a narrow neck. So people could put a couple of soldiers on the neck and nobody can get out of Boston—you know, it's almost like an island.

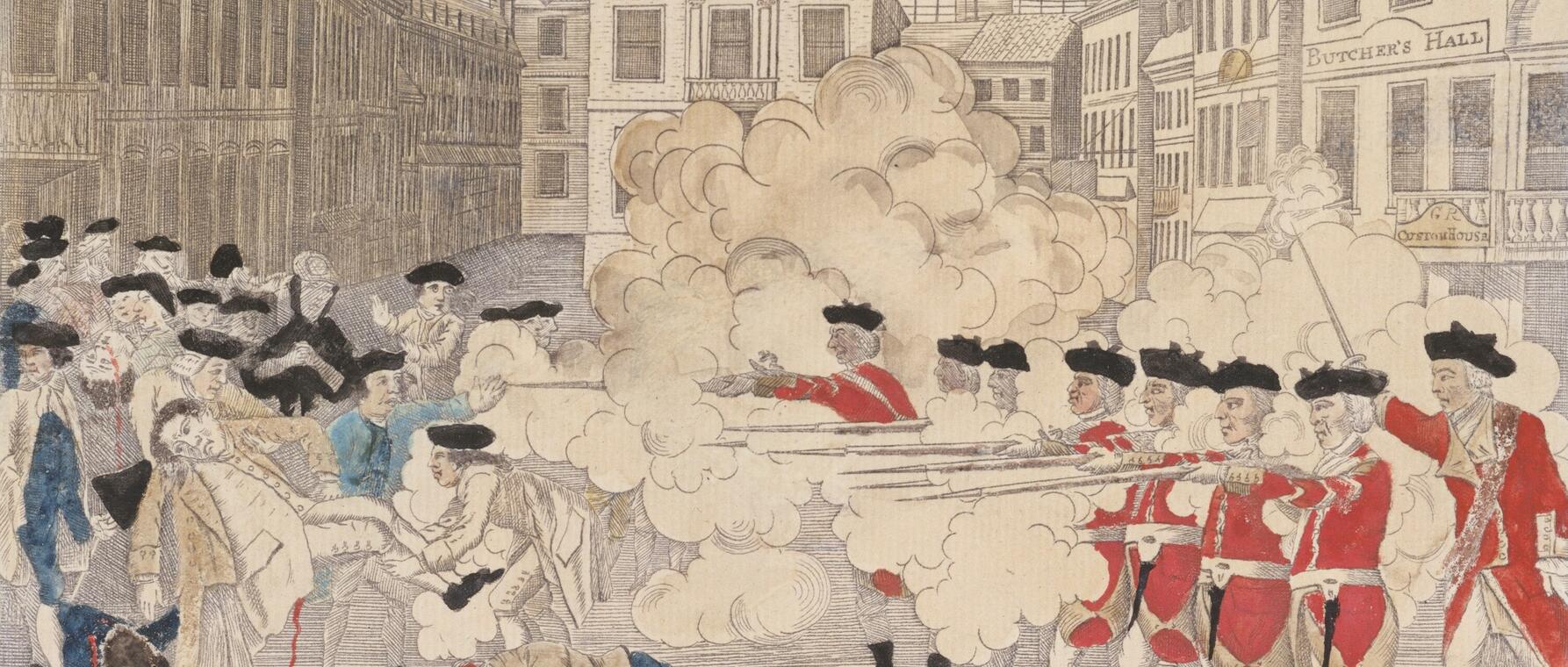

Relations were difficult at the beginning, and then they just got worse. The British burned a lot of Bostonian possessions because they got cold in the winter, so they'd go into houses and take furniture—burning books, kind of a sacrilegious thing for a Bostonian. And then the culmination of this first occupation is the Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770, when it's just a standoff.

It was a cold day, so there was snow and ice, and the Bostonians started throwing snowballs at the soldiers, who shot back and killed 5 people. And that was a really big deal. The English actually withdrew the soldiers because it was just an unmanageable situation.

In the time of the religious arguments and the English Civil War, and even a little before that, there's a feeling that standing armies are a terrible thing for any self-respecting quasi-democratic society—that they inevitably encroach on people's rights and go into their homes . . .

That occupation ended after the massacre and some good things happened. As mad as the Americans were, they had a fair trial. And that's something of great interest in 2026. Are there going to be trials for occupying (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) ICE agents in Minneapolis and in other cities? [Some federal] officials have said [the agents] have “total immunity.” The British king had also implied immunity. There was an incident shortly before the Boston Massacre where a soldier shot and killed an 11-year-old boy, and there was a huge outcry, and the king pardoned him.

So, it's one thing when a murder or some kind of physical injury is sustained—that's a crime in any society. But then when the perpetrator has official power and is immediately pardoned by the state that he works for, that's the kind of second problem where you feel like there's just no accountability. And after the Boston Massacre, Bostonians did very well. They allowed a legal trial to happen, a fair legal trial. And John Adams, who was on the side of the patriots, defended the British soldiers and got them mostly off of all the charges. So that showed the law still working in Boston. But a few years later, there's a second occupation. And, you know, it's even worse than the first one.

There's this idea among the colonists of a duty to resist immoral laws and commands. Can you talk a little bit about how that idea really is in the founding DNA of the United States?

It's really in New England's founding DNA, for sure. And Boston, especially. We take it very seriously. We don't want to be pushed around by kings or the generals they send over. We remember stories from our grandfathers and great-grandfathers who founded Massachusetts, that they stood up bravely to the troops in their own way. So, throughout a pretty long time—Boston’s founded in 1630, and then these tensions are in the 1770s—so it's 140 years. It's a long time.

But they're passing down these legends, and the legends are reinforced by the ministers and the town officials, and they're really all bound together. Religion is so central to the idea of living in a Massachusetts town. The minister of the local Congregational church on the village green is an important civic official as well as a religious official.

One of them was a guy named Jonathan Mayhew, who in 1750 gave a pretty incendiary speech about how if the British tell us to do something that goes against our conscience, not only do we have the right to disobey, we must disobey. It's getting to be close to Martin Luther King and Gandhi—that an immoral government telling us to do an immoral thing must be resisted by a people of conscience.

So they take that very, very seriously. And Mayhew's—I mean, he's just a guy in the middle of the 18th century, but each statement like that leads to the next one. So in 1761, well before the revolution starts, there's a famous legal argument in Boston, a guy named James Otis, who is an inspiration to John Adams.

So they all—each one leads to the next—he gives a long and impassioned argument against these warrants of dubious legality called writs of assistance. “You can't just come into our houses with a quickly drawn-up writ of assistance that isn't proper. You haven't submitted it to a judge. We don't know what you're looking for. We don't know the source of this information.” And often, to get a good warrant, a soldier would have to say who the informant was. Who told them there was some whiskey stored in this guy's basement? And so, naturally, the Bostonians wanted to know who the informant was so they could go beat him up, you know? So there's tensions on all sides, and each level of New England resistance made the next one possible.

In the country’s 250th anniversary year, there’s obviously a temptation to historicize the events in Minneapolis and other US cities. What sort of caution would you advise here, and how can knowledge of the past inform the moment that we're living through now?

Well, you're right to interpret that I had Minneapolis on my mind as I wrote about Boston in the 1760s and 1770s. I had studied the American Revolution a lot at Harvard Griffin GSAS, and I'd walked the trails—you know, even before Harvard, I walked the Freedom Trail. I grew up not too far away. So, it was sort of in my own DNA, this idea of resistance to a distant authority. And as I saw not just the murders of René Good and Alex Pretti, but the incredible courage of the ordinary people of Minneapolis, I thought that, too, is like Boston.

But you're right to also say that no two historic episodes are identical. We're in 2026. It's more than 250 years after both occupations of Boston, and those two were not identical to each other. Boston was a much smaller city than Minneapolis is. It was dealing with foreign troops; in Minneapolis, we’re dealing with fellow Americans, which, you know, adds to the tragedy in a way.

So I tried to point out a few of the differences, too. But then even as I did that, I thought, you know, it's not really that different because English and New Englanders thought of themselves as kind of cousins. You know, they weren't that foreign to each other. So even in that way, I thought it was somewhat similar.

Finally, your time in the White House as senior advisor and speechwriter for President Clinton spanned the years after public outrage over the behavior of federal law enforcement officers during the standoff at Ruby Ridge in Idaho and the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas. How did we get from widespread, bipartisan condemnation of federal law enforcement to what's happening now in Minneapolis, where, despite some outrage, there is a substantial portion of the country that’s on board with very aggressive tactics?

I think if we want to be honest with ourselves, we have to admit there have been violent people in the margins since the writing of the Constitution—Shays’ Rebellion, the Whiskey Rebellion—people who did not like the idea of even the very modest central government we were creating in the 1780s and ’90s. There were Americans even then who were outraged by it.

And there have been left-wing mobs and right-wing mobs protesting the federal government or state governments ever since. What happened in the ’90s? There was a feeling of profound anger on the right against government overreach. But then what turned it around pretty dramatically in the middle of the ’90s was the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, which took it way too far in the other direction. This was an act of terrorism. I think that word absolutely applies. Killed over 100 people, including small children, just because Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols were mad at the federal government. That's not an acceptable form of political expression of your beliefs. And I think Bill Clinton did a good job, you know, talking about it in a way that explained why violence is unacceptable. And that did, I think, tamp down some of that anger at the beginning of the 1990s.

I think if we want to be honest with ourselves, we have to admit there have been violent people in the margins since the writing of the Constitution—Shays’ Rebellion, the Whiskey Rebellion—people who did not like the idea of even the very modest central government we were creating in the 1780s and ’90s. There were Americans even then who were outraged by it.

But we saw it throughout the 21st century. I mean, it's happened a lot. The Tea Party was not violent, but it was certainly angry over tax issues. Then we saw pretty significant protests when African Americans were killed by police, with George Floyd being the most serious example. That was an act of local police, not the federal government. So, there was vivid anger on the left.

That was followed by January 6, which is still sitting there like a festering wound in our recent memory. But now another flip has happened because it's the left now, not the right, that is angry over the ICE raids in Minneapolis. And I'm sure there are other ICE raids coming. I think this is only a temporary Christmas truce we're in. Much more is coming.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast