Summer of Discovery

GSAS programs help students from underrepresented groups explore Harvard and an academic life

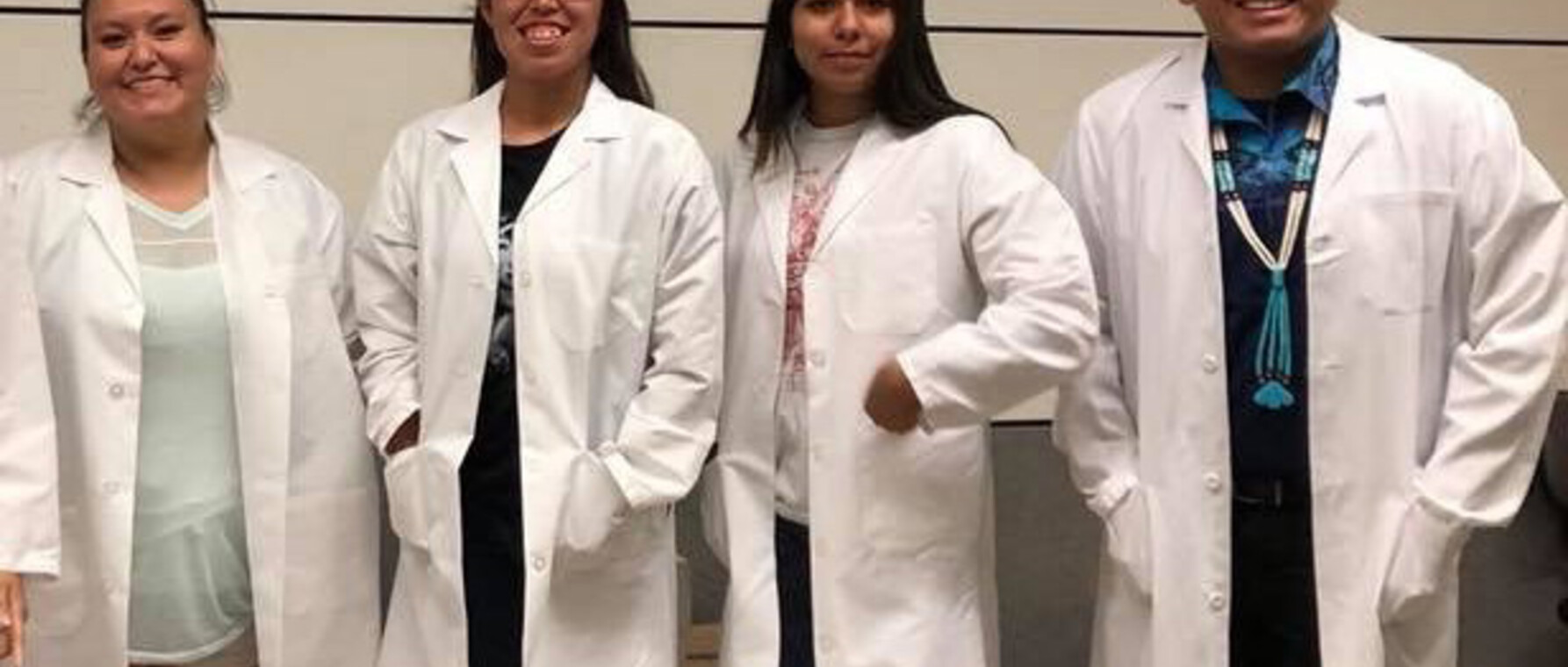

Friends Kaeleigh Cain and Patricia Sieweyumptewa have a lot in common. Both are Native Americans who grew up on a reservation. Both have a passion for service and for working with young people in their communities. And, until they participated in the Ed Furshpan and David Potter Native American High School Program at Harvard (NAHSP), neither thought they’d ever study science.

“Before NAHSP, I wasn’t really interested in the medical field,” says Cain, “but I participated because I wanted to see what it was. I discovered that I really liked medicine, so I decided to switch my career goal.”

Cain, Sieweyumptewa, and many other students have had the chance to work with scientists in small group lab sessions, attend lectures, and participate in professional development activities through the NAHSP, which is run by Harvard’s Division of Medical Sciences, and through programs overseen by the Office of Diversity and Minority Affairs (ODMA) at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS). As part of the School’s efforts to diversify the academy and the professions, the programs enable students from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds to pursue graduate study in the sciences, define their career paths, and make connections crucial for success.

A Scholar and a Role Model

A member of the Dakota tribe, Cain spent her childhood on the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana. In high school, she studied hard and made the National Honor Society. When she wasn’t hitting the books, she was usually volunteering to benefit the community: running winter clothing drives for elementary school students, distributing turkeys on Thanksgiving, even throwing a Halloween carnival for the kids on her reservation.

“I really liked doing the service because it was an opportunity for me to get to know people in my community better, to help them out more,” says Cain.

Cain came to the NAHSP to learn about the science of substance abuse and addiction as well as what she could do to help address the problem in her home community. Launched in 2001 by Ed Furshpan and David Potter, two emeritus HMS faculty in neurobiology, the program is a partnership with the Hopi and Fort Peck tribes that aims to increase the number of students from Native American communities who pursue and complete a college degree and consider careers and advanced degrees in STEM and health. Sheila Thomas, dean for academic programs and diversity at the GSAS and faculty director for diversity in the Division of Medical Sciences, says NAHSP from its inception, was established as a collaboration between Professors Furshpan and Potter and leaders and members of the participating nations.

"For example, the neurobiology of addiction became a focus because the members of these communities indicated it was an issue they were facing," she says. "Ed Furshpan and David Potter wrote a case study to teach students the science, but it was a white suburban story. Kenny Smoker, director of the Health Promotion/Disease Prevention Program at the Fort Peck Reservation, actually rewrote the case to make it more relevant to the students"

Cain says the program provided her with much-needed guidance and advice on how to apply to college and finance her education.

“It was really valuable because as a Native American, we’re not really taught much about college on our reservation,” she says.

After graduating from high school and enrolling at Minot State University in North Dakota, Cain returned to Harvard for the Summer Honors Undergraduate Research Program (SHURP). Launched by the Office of Diversity in the Division of Medical Sciences nearly 30 years ago by Professor Jocelyn Spragg, the 10-week program brings college students from underrepresented backgrounds to labs at Harvard Medical School where they work with faculty. SHURP Co-director Karina Gonzalez Herrera says that the students not only gain laboratory and research experience but also continue to strengthen academic and professional skills crucial for acceptance to graduate programs—and for success after their formal education is done.

“We have faculty talk to the students about how to prepare an effective presentation and how to search the original scientific literature,” she says. “We work with them on how to present their research and ask them to do their own ‘TED Talk.’ We also discuss topics like how to prepare a strong application for graduate programs and what careers they can pursue beyond a PhD or an MD-PhD degree. During the program, the students build connections by interacting with members of the Harvard community and by attending a conference to present their work at the end of the program.”

[NAHSP] was really valuable because as a Native American, we’re not really taught much about college on our reservation.”

In the three decades since its establishment, SHURP has welcomed over 600 students from colleges across the United States. More than 90 percent have gone on to PhD, MD, or MD/PhD programs. And while more than 100 SHURP alumni have enrolled at GSAS, Gonzalez Herrera says that the goal is to help students discover the path that’s right for them—wherever it may lead.

“If the students want to pursue their graduate education at Harvard, yes, we would love to have them,” she says. “Our aim is to help students identify what they need and find the best fit for them.”

The best fit for Cain right now is the study of medical laboratory sciences at Minot State—although she recently participated virtually in yet another Harvard program where she learned to work with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) lab equipment, which enables scientists to study DNA by amplifying small samples. Cain hopes to become a microbiologist and serve as a role model for the youth in her community.

“I would like to become a microbiologist, go to graduate school for it, and then be able to come back to Fort Peck as a role model for the youth there,” she says. “I would also like to work at our Indian Health Services. We need more people with qualifications to serve our community.”

A Commitment to Youth. An Interest in the Brain.

At NAHSP in 2016, Cain met Sieweyumptewa, a member of the Hopi Tribe of Arizona. (Sieweyumptewa’s mother, LaVonne Honyouti, a biology teacher at Hopi Junior Senior High School, has also been a key partner in NAHSP since 2001, selecting the participating students, serving as a chaperone, and helping to shape the overall program.) Cain and Sieweyumptewa quickly became friends. Sieweyumptewa, like Cain, was an honors student who spent much of her spare time serving in her community—volunteering for book drives, reading to elementary school kids, and participating in the National Honor Society. In high school, she knew that she wanted a career working with children at the reservation on which she grew up. She wasn’t sure what form that would take, though, or what course of study to pursue.

“Before attending the Native American High School Program, I really had no idea what I wanted to go to school for,” she says. “I only knew that I wanted to come back and help kids in any way possible.”

NAHSP led Sieweyumptewa to the University of Arizona for college and then back to Boston for GSAS’s Summer Research Opportunities at Harvard (SROH) program. Like SHURP, SROH takes place over 10 weeks and is geared toward undergraduates from underrepresented backgrounds. SROH accepts students with a wider range of academic interests, though, including the humanities and social sciences. Stephanie Parsons, assistant director of Diversity and Minority Affairs at GSAS says that the goal is to prepare them to gain admission to—and complete—a PhD program.

“SROH is specifically for undergraduates who are interested in a PhD,” says Parsons. “We connect students with top researchers working not only in the life and physical sciences, but also the humanities, and social sciences.”

At SROH, Sieweyumptewa interned in Dr. Mina Cikara’s Intergroup Neuroscience Lab. There she explored empathy and the workings of the human brain and furthered her interest in cognitive science, first kindled at NAHSP.

“I worked on a project that showed how episodic simulations make you recreate scenes in your mind and how you can picture certain things in your head,” Sieweyumptewa says. “I learned how these simulations influence how we empathize with people of our in-group versus people in other groups.”

Like Cain and the students in SHURP, Sieweyumptewa also received academic advice and learned skills to foster her success in graduate school and beyond. Parsons says that SROH participants learn to write a statement of purpose, to apply for national fellowships, to organize their time, and to think about budgeting for school. Parsons says that the program is designed to upend the assumptions and the anxieties that keep underrepresented students from considering a PhD at a school like Harvard.

Before attending the Native American High School Program, I really had no idea what I wanted to go to school for. I only knew that I wanted to come back and help kids in any way possible.

“We want to break down the myth that a school like Harvard is not welcoming or would be too demanding,” she says. “At SROH, students get interested and energized rather than defeated and demoralized. And when they take that experience back to campus and spread the word among their classmates, the impact of the program is multiplied. It’s better than any poster or ad we could create.”

Sieweyumptewa took her SROH experience back to the University of Arizona, where she is now a junior studying psychology. In the years ahead, she hopes to conduct research that furthers understanding of addiction. Ultimately, she wants to become a counselor and work with the youth on her home reservation, serving as a role model for what they can accomplish.

“I want to connect with kids and let them know that college is an option,” she says. “I want to provide them with resources and share my experiences on how I went about getting an education.”

Cain and Sieweyumptewa say that the skills, information, and experience they gained at NAHSP, SHURP, and SROH have changed their lives and careers. And yet, the part of the program that has had the most lasting impact is the bond they forged with each other. As the two move forward in their careers, they will look not only to the knowledge they gained at Harvard but also to each other to realize the aspirations they have for themselves and their communities.

“Patricia and I have been friends since 2016,” Cain says. “We talk every day. Wherever I go in my life and career, I’ll always be able to say that I met one of my best friends during one summer at Harvard.”

Photos courtesy of Kaeleigh Cain and Patricia Sieweyumptewa

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast Stitcher